"An experience that transforms something inside us"

Beauty, possibility, and Beethoven in Haruki Murakami's Kafka on the Shore.

"You gotta hear this one song. It'll change your life, I swear."

With those simple sentences, delivered with wide-eyed glee by Natalie Portman's Manic Pixie Dream Girl character, the 2004 film Garden State taught legions of disaffected 20-somethings that all you need is one great tune — in this case, The Shins' "New Slang" — to radically alter your perception of the world. Based on sales figures for the movie's soundtrack album, "New Slang" has changed at least one million lives in the United States alone.

In the literary world of Haruki Murakami, however, it's Ludwig van Beethoven's music that holds the power to change your life — an alchemical process the Japanese author traces throughout his 2002 novel, Kafka on the Shore.

Within the book's pages we meet Hoshino, a long-haul trucker in his mid-20s who's become numb to the uneventful life he leads on the road. The occasional hookup and watching his favorite baseball team, the Chunichi Dragons, are the only stimuli capable of penetrating his emotional fog. But when he takes pity on Nakata, an older illiterate gentleman who needs to travel from Tokyo to Takamatsu for reasons he can't effectively communicate, Hoshino embarks on a wild adventure across Japan, where he encounters leeches falling from the sky, talking cats, and a mysterious pimp who looks and talks just like Colonel Sanders. (Yes, that Colonel Sanders.)

Fighting boredom one afternoon while Nakata naps, Hoshino visits a coffeehouse. There he's enchanted by the music playing over the sound system — Beethoven's "Archduke" Trio for piano, violin, and cello.

Music has never played any role in Hoshino's life, and he doesn't peg himself as someone who could "get" classical music. But Beethoven's trio quickly becomes an obsession. He buys a CD of the work and pores over biographies of the German Romantic composer at a local library he visits with Nakata. It's there that he strikes up a conversation with the library's front desk attendant, Oshima, a classical music aficionado. Unsure of the effect Beethoven's music is having on him, Hoshino asks him:

"Do you think music has the power to change people? Like you listen to a piece and go through some major change inside?"

Oshima nodded. "Sure, that can happen. We have an experience — like a chemical reaction — that transforms something inside us. When we examine ourselves later on, we discover that all the standards we've lived by have shot up another notch and the world's opened up in unexpected ways. Yes, I've had that experience. Not often, but it has happened. It's like falling in love."

Hoshino had never fallen head over heels in love himself, but he went ahead and nodded anyway. "That's gotta be a very important thing, right? he said. "For our lives?"

"It is," Oshima answered. "Without those peak experiences our lives would be pretty dull and flat. [Composer Hector] Berlioz put it this way: A life without once reading Hamlet is like a life spent in a coal mine."

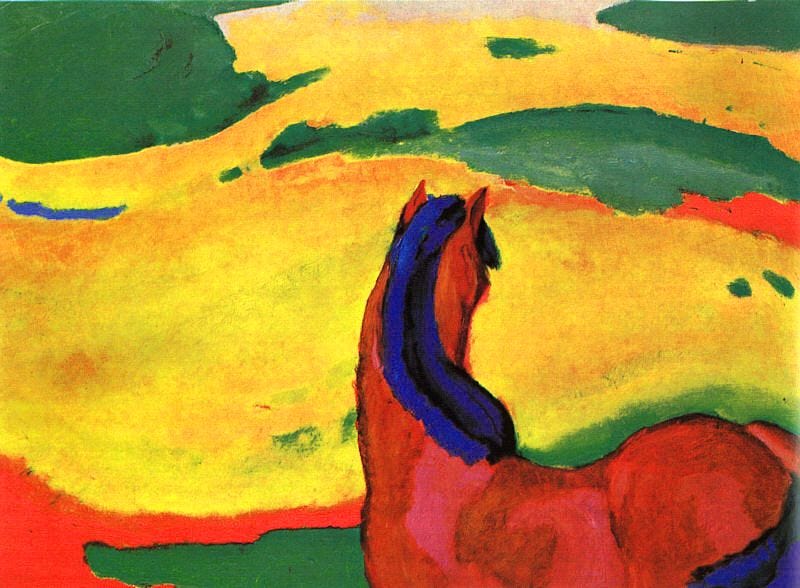

With repeated listens to Beethoven's trio, Hoshino grows increasingly intrigued by the composer's life story and the unfamiliar experience of feeling his body absorb and respond to this music. Like Dorothy discovering the Technicolor landscapes of Oz right outside her sepia-toned front door, Hoshino now finds himself moving through the world with fresh eyes and an increasingly curious heart. His metaphysical encounter with Beethoven's music serves as a clarion call to seek out the beauty that surrounds him, to lead a life powered by possibility.

Just as Hoshino faced a crossroads in his life — either return to his disconnected existence on the open road or forge new paths of freedom and novelty — so too did Beethoven stand at an important intersection as he wrote the "Archduke" Trio in 1811.

Over the prior decade, the 41-year-old had composed dozens of major works — from symphonies to solo piano sonatas, string quartets, and concertos — that reimagined music's potential. With every new composition, Beethoven broke many of the rules baked into these established forms, expanding not only their structural scope, but also the depth of emotions conveyed.

But at the same time, he was confronting the reality of his worsening hearing loss, which, by the time he premiered the "Archduke" Trio in 1814, had greatly impacted Beethoven's perception of speech and music. Just five years before, as the Napoleonic Wars raged outside his door in Vienna, Beethoven had taken refuge in his brother's basement, where he covered his ears with pillows in an attempt to protect what remained of his hearing.

Although he was plagued by the fear of people discovering his disability — to the point that he had considered committing suicide — Beethoven had cultivated a steely fortitude in the years in which his hearing declined. He was a stern, uncompromising character in many aspects of his life, but none so much as matters related to his art. Beethoven was determined to "seize Fate by the throat," as he wrote to a close friend. "It shall certainly not crush me completely."

That overwhelming struggle to conquer Fate is evident in so much of Beethoven's music, its white-hot intensity seemingly capable of igniting flames on the page. But in the "Archduke" Trio, he shows us a gentler, nobler side of his character, one inspired by friendship.

The trio's nickname refers to its dedicatee: Archduke Rudolph of Austria, an amateur pianist who for years served as one of Beethoven's most generous financial supporters. Despite the chasm of class disparity between them — Rudolph the wealthy aristocrat and Beethoven the poor freelance musician — the pair developed a close friendship of mutual respect that lasted until Beethoven's death in 1827.

Perhaps as a symbol of gratitude toward his dear friend and supporter, Beethoven infuses his piano trio with a sense of gemütlichkeit, a Germanic term applied to feelings of supreme comfort and calm. And nowhere in the piece does he convey those feelings of warmth and familiarity more than in its slow movement.

Here Beethoven composes a set of variations — a favorite form of his, in which he takes a simple melody and transforms it, one imaginative iteration at a time, into a grand statement of musical poetry. But unlike many other composers of his day, who used the variation form to showcase the complexity of their counterpoint or offer players flashy passages to showcase their technical talents, Beethoven unites the voices of piano, violin, and cello in an act of communal prayer. The musicians breathe, sing, and sigh as one body — harmonizing a soulful hymn in one moment, teasingly mimicking each other the next, and ultimately finding rest as the music dissolves into rapt silence.

As much as this music comforts and consoles us today, for Beethoven, the "Archduke" coincides with a moment of profound loss. During preparations for the trio's premiere in 1814, where Beethoven played the piano alongside a pair of close friends, violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh and cellist Josef Linke, his hearing loss proved an obstacle he could no longer overcome. Rehearsals were a disaster for everyone involved, as the composer Louis Spohr later recounted in a letter:

"It was not a good performance. ... On account of his deafness, there was scarcely anything left of the virtuosity of the artist which had formerly been so greatly admired. In [loud] passages the poor deaf man pounded on the keys until the strings jangled, or he played so softly that whole groups of notes were omitted, so that the music was unintelligible.

I was deeply saddened at so harsh a fate. It is a great misfortune for anyone to be deaf, but how can a musician endure it without giving way to despair? Beethoven's almost constant melancholy was no longer a mystery to me."

After that concert, Beethoven never played the piano in public again.

It's fitting that in this final trio, Beethoven turned to the variation form, in which the musical material undergoes a relentless amount of change. Because in order to maintain music as a form of income, of personal expression, of spiritual development, Beethoven had to endure a similarly relentless amount of change. He had to adapt and evolve and figure out a way to transcend his disability and continue creating music. After the "Archduke" premiere, Beethoven knew life as a performer was no longer possible. So it was imperative that he be able to share his thoughts with the world as a composer.

His work became his mode of defiance and survival. Fueled by an unceasing rage to defy Fate, Beethoven painted vivid musical portraits of his emotional struggles, right up until the end of his life. But in the celestial sounds of the "Archduke" Trio's variations, he gives himself a chance to relax, to play melodies of glorious beauty with his friends, as their hearts beat in time with the music that flowed from his pen.

This music invites us to consider how our human hunger for beauty can fuel a renewed sense of possibility in our lives, despite our mistakes and the obstacles we face — an important lesson Hoshino learns at the end of Kafka on the Shore. Preparing to return home after his fantastical adventures with Nakata come to a close, he reflects one last time on his newfound connection with Beethoven:

"I've done some awful things in my life. I was pretty self-centered. And it's too late to erase it all now, you know? But when I listen to this music, it's like Beethoven's right here talking to me, telling me something like, It's okay, Hoshino, don't worry about it. That's life. I've done some pretty awful things in my life too. Not much you can do about it. Things happen. You just got to hang in there. Beethoven being the guy he was, he's not about to say anything like that. But I'm still picking up that vibe from his music, like that's what it's saying to me. Can you feel it?"

During this season of rebirth and renewal, I hope you choose to follow in Hoshino's steps — to pursue endless paths of possibility inspired by Beethoven's mystical variations. This one song will change your life, I swear.

Beaux Arts Trio Menahem Pressler, piano Isidore Cohen, violin Bernard Greenhouse, cello

Thank you to everyone who has supported Shades of Blue this year — by reading my work, upgrading to a paid subscription, or recommending this newsletter to friends and loved ones. I'm excited to experience even more moments of melancholy music with you in 2025. I'll be back in your inboxes in mid-January.

In the meantime, I wish everyone an enchanting holiday season and a new year filled with safety, security, and good health.

This newsletter is free, but paid subscribers help support the 20+ hours of research, writing, editing, and production that goes into every essay. If you look forward to reading Shades of Blue when it arrives in your inbox, please consider becoming a paid subscriber …

Or if you'd like to buy me a coffee as a token of thanks for this article, you can make a one-time donation to support this newsletter:

Love this article, Michael! I often teach this book and we do a lot with the musical and artistic allusions. One student of mine (a talented musician) wrote a senior research paper with this topic. If I teach this next year, I shall share your essay for sure.

Thank you, Michael, for a year of great music and writing. Happy Holidays!