Benjamin Britten / Before Life and After

A profound expression of love and longing for innocence in a world wracked by tragedy.

Discovering the work of Benjamin Britten didn't just open up a whole new world of brooding, beautiful music for me to explore. The composer also served as a portal connecting me to a feast of literary delights.

Through his opera The Turn of the Screw, I came to know Henry James's gothic tale of ghostly possession. The massive War Requiem — written to consecrate the new Coventry Cathedral after the medieval structure was obliterated by German bombs during World War II — brought me face-to-face with Wilfred Owen's lyrical anti-war poetry. And the dozens of songs he composed throughout his storied career introduced me to the writing of Auden, Michelangelo, Rimbaud, Blake, and Donne.

Britten's body of work excludes many of the traditional forms classical composers often explore to prove their mettle. He didn't write any formal symphonies or piano sonatas, and only a handful of string quartets and concertos. Instead, the lion's share of his output is a symbiotic marriage of text and music. But why exactly did Britten compose so much music for the voice?

He had a staggering talent for setting texts, of course. From arranging English folk songs to composing his own song cycles, operas, and choral music both sacred and secular, there were few vocal forms Britten didn't imbue with his signature ability to illuminate poetic scenes through music.

But outside of any question of artistic practice or technique, Britten also had a very personal reason to write for the voice — one specific muse for whom the composer wrote many of his songs and his greatest stage roles: Peter Pears, one of the finest tenors of his day and Britten's life partner for 39 years.

For much of those four decades, Britten and Pears zigzagged across the globe — from Austria to Australia, and from Southeast Asia to South America — performing recitals of Britten's music. Together they became the United Kingdom's most prominent musical ambassadors abroad and national treasures at home, a favorite of audiences ranging from schoolchildren to Queen Elizabeth II.

The popularity Britten and Pears amassed lay in direct conflict with the conservative values of England in the first half of the 20th century. They were pacifists and conscientious objectors in a grueling era of world war. They were socialists at a time when the political framework was tainted by autocracy and totalitarianism. And they were homosexuals in a country highly intolerant of sexual minorities. For the first 30 years of their relationship — nearly half of each man's life — the love they shared could have destroyed their careers and landed them in jail. But despite the potential for persecution in his home country, Britten forever placed his music in service of the English people and their collective cultural history.

That perspective the couple shared, as sexual and political outsiders, is one of the principal threads Britten laced into his music. In ways both coded and confrontational, the composer explored the conflicts between innocence and experience, society and its outcasts, public versus private personas — themes also found in the writing of Thomas Hardy. Although the two never met (Hardy died when Britten was just 13), the composer saw Hardy as a kindred spirit: someone whose work was also rooted in English history and culture, whose writing, steeped in melancholia, carried a tremendous sense of humanity and understanding for those held at the fringes of society.

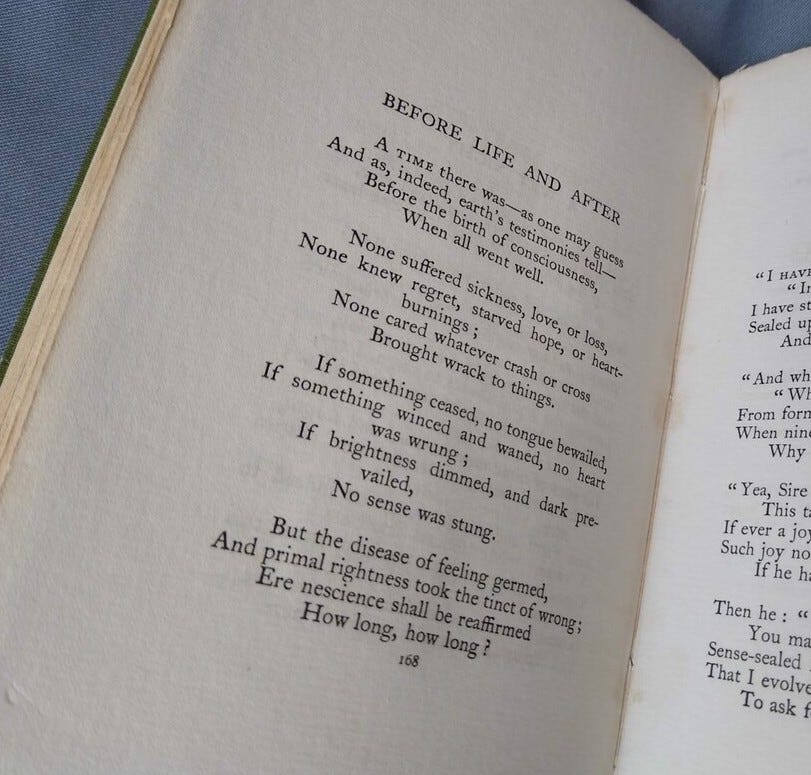

Inspired by his and Pears's shared love for Hardy's poetry, Britten composed his Winter Words song cycle in 1953, setting to music eight of Hardy's poems that capture a kaleidoscopic view of daily life in mid-19th-century England — a world of cramped train journeys, impoverished child buskers, and rain-soaked funeral services. But in the collection's final song, "Before Life and After," Hardy takes us well out of any specific time or place, transporting us to the days of Edenic bliss, before the birth of human consciousness, a time "when all went well."

The poem's first three stanzas paint a vivid portrait of humankind before the fall: a world without sickness or loss or regret, a time when we weren't fearful of the world's ever-present darkness. Then, in the final stanza, an intense longing for a return to that palace of primal innocence takes over. Its final words, "How long, how long?" leave us to wonder when — or even if — we'll ever be relieved of this emotional crisis.

Britten's setting of the song, barely three minutes of music, may sound simplistic when compared to the gravity of Hardy's text. But as is often the case with Britten's music, the world of complexity that lies beneath the song's surface is key to understanding Britten's compositional style, which, as the New Yorker's Alex Ross perfectly states, uses "simple means to express fathomless depths."

Marked "quietly moving, always soft and smooth," the music for the first three stanzas is filled with intimate reverie for those fabled days. The melody begins in the singer's highest register, filled with sighs and falling phrases. Underneath this vocal line, Britten provides a languid, unadorned counterpoint in the piano's right hand, while the left hand marches with an insistent rhythm in the depths of the piano, like the soft crunching of grass underfoot.

Built on the most basic building blocks of traditional harmony, the triad, the music keeps moving us forward, delivering momentary reprieve only in the final line of each stanza. In these moments, Britten catches his breath with a bar of sustained chords before the marching motion begins anew.

But as we enter the final stanza, when "the disease of feeling germed / And primal rightness took the tinct of wrong," the music grows to an unbearable intensity. Instead of the sighs and gentle downward motion our ears have gotten used to, the vocal line begins low and continues upward, striving to move ever higher, phrase by phrase, culminating in a searing eruption of emotion. As the voice cries out with the poem's final question, "How long?" the piano's right-hand figure mimics the pealing of bells, the left hand's insistent rhythms now a fervent march of souls demanding a return to innocence.

Unlike Hardy, who only poses the question twice, Britten broadens his music to deliver the question five heartbreaking times. Of course, neither Hardy's poem nor Britten's song answers that profound question, leaving us to continue our search for deliverance in an ever-hardening world filled with tragedy and fear.

But on the other side of that tragedy and fear lies love. Like all of the songs Britten wrote for Pears, "Before Life and After" is a manifestation of the love the couple shared — which they in turn shared with people around the world through their music making. The song would go on to hold a special place of importance for Britten late in his life.

Twenty years after he wrote Winter Words, Britten was in a bleak physical and emotional state. While undergoing heart surgery to replace a faulty valve, he suffered a mild stroke that greatly weakened his right arm. The act of composing had become physically challenging, but in 1974 Britten was trying to stay focused on what would ultimately be his last work for orchestra: the Suite on English Folk Tunes, a collection of the composer's favorite folk music from his childhood. To that nostalgia-laced work, Britten added the subtitle "A time there was ..."

To understand the placement of the first line of Hardy's poem on the suite's title page, we can turn to one of the couple's many tender and heart-melting letters. Shortly after Britten finished sketching the new suite, he wrote to Pears in New York:

"My darling heart … I feel I must write a squiggle which I couldn't say on the telephone without bursting into those silly tears —

I do love you so terribly, and not only glorious you, but your singing. I've just listened to a re-broadcast of Winter Words, and honestly you are the greatest artist that ever was — those great words, so sad and wise, painted for one, that heavenly sound you make …

What have I done to deserve such an artist and man to write for? …

I love you,

I love you,

I love you — B."

Already swept up in the memories his folk song suite conjured, and with Pears thousands of miles away for the Metropolitan Opera premiere of Britten's final opera, Death in Venice, hearing Winter Words prompted not only a spectacular confession of love from Britten, but a means to encode that love for Pears forever in his new work. And having come to terms with his declining health and accepting that the days he had left were far too few, he chose to express that love both nobly and unabashedly.

Take a listen …

Thankfully for us, Britten and Pears spent a lot of time in the recording studio. So when it comes to listening to "Before Life and After," the best place to turn is the couple's own performance. Feel the warmth of Pears's tenor, the way he's able to float the melody while delivering the text with perfect clarity. Savor the intimate interplay between melody and accompaniment, delivered by two musicians who felt the pulse of each other's hearts as strongly as that of their own. I dare you to listen without tearing up!

And a special treat …

Britten wasn't just a phenomenal composer of art songs, he was also an expert arranger of English folk music. My favorite of these settings has always been the "Corpus Christi Carol," an early 16th-century hymn of love and loss Britten arranged as a 19-year-old student at London's Royal College of Music. Although the recording by Janet Baker — a close friend of Britten and Pears — is the go-to for many, I always turn to Jeff Buckley's melancholy version. If heaven exists, I hope Jeff and his seraphic voice welcome me into paradise with this song.

I'd love to hear about your experience listening to Britten's song of love and longing. Let me know in the comments.

If you enjoyed your time here at Shades of Blue, how about tapping that little heart below? 👇🏼

I really enjoyed reading this appreciative piece, Michael.

My perspective on Britten was largely shaped through my reading of W.H. Auden - "Our Hunting Fathers" - and the Davenport-Hines biography of Auden.

But this article opened a new window on Britten's work. Great stuff, Michael!

Your piece on Britten and Pears is wonderful for its sensitivity and depth. It provides such a great opportunity to explore Britten’s work and Pears’ voice.

I read it last evening and immediately thought about an incident some forty years back.

I was working in a London Ad Agency. We’d just won the Tolly Cobbold (Suffolk Brewer). Mike Doyle the creative director came up with the idea ‘Suffolk Originals’ to extol their lead brew ‘Tolly Cobbold Original’ Then of course there was a scramble for other Suffolk Originals for the poster campaign.

Doyle wanted to include Britten as a ’Suffolk Original’ now deceased. However Pears had to give permission. Doyle raced out of London, some 100 miles, up to Aldeburgh to see Pears and seek his blessing. The two of them passed a pleasant day together and approval was granted.

In developing the idea Doyle sought out Britten’s music. He bought dozens of cassette tapes. Sometime later he had a clear out of his desk. I nabbed one cassette, a recording of Britten’s Gloriana Symphonic Suite Op. 53. I was not familiar with the work. I played it and was hooked (have been ever since).

Link to the work on YouTube. https://youtu.be/tVdqIYAKU_I?si=QsmsIQWtlTnuNb5F

Thank Michael for a great piece of work.