Clara Wieck Schumann / Piano Concerto

At the center of a silent orchestra, piano and cello sing a tender song of grace and longing.

If you've heard the name Clara Wieck Schumann before, chances are she was portrayed as a muse to her husband, Robert Schumann — a committed companion and stabilizing force who encouraged his work and, in the decades following his early death, cemented his legacy as one of German Romanticism's most gifted composers. While that longtime depiction of Clara is true — she was indeed a sensitive and supportive muse, to Robert as well as the couple's close friend Johannes Brahms — her impact on 19th-century classical music travels far beyond that border. Only in the past 30 years have the history books begun to illuminate the full scope of her life and work.

Clara was one of the finest performers of her day, an acclaimed solo pianist who, after making her debut at the age of nine, maintained an astonishing seven-decade career as a concert artist — while also serving as her own manager, promoter, and agent. She was among the first to regularly play Bach and Beethoven on the concert stage and helped establish new standards for pianists, like performing from memory. At 18 she was named Royal and Imperial Chamber Virtuoso of the Austrian Court, by which point her playing had been hailed by the biggest names in music, including pianists Franz Liszt and Frédéric Chopin and violinist Niccolò Paganini. Off stage, she raised eight children, managed household finances, and served as the family's primary breadwinner (and after Robert's mental collapse and death, its sole earner).

So yes, Clara propelled Robert to greater heights in his artistry, so much so that his name eclipses hers in music history. But when the couple wedded in 1840, Clara was the internationally renowned celebrity and Robert a relatively unknown composer and music critic.

The daughter of two pianists, Clara was immersed from a young age in the musical world of Leipzig, Germany, where she met the major figures who swept through town on European concert tours. As a result, Clara's teenage compositions reflect the same influences as those of her older male contemporaries. She embraced the ornate melodies of Italian opera, infused her work with a dazzling virtuosity that matched Paganini, and found inspiration in music both old and new, from J.S. Bach's freshly rediscovered keyboard works to Hector Berlioz's orchestral opium dream, Symphonie fantastique.

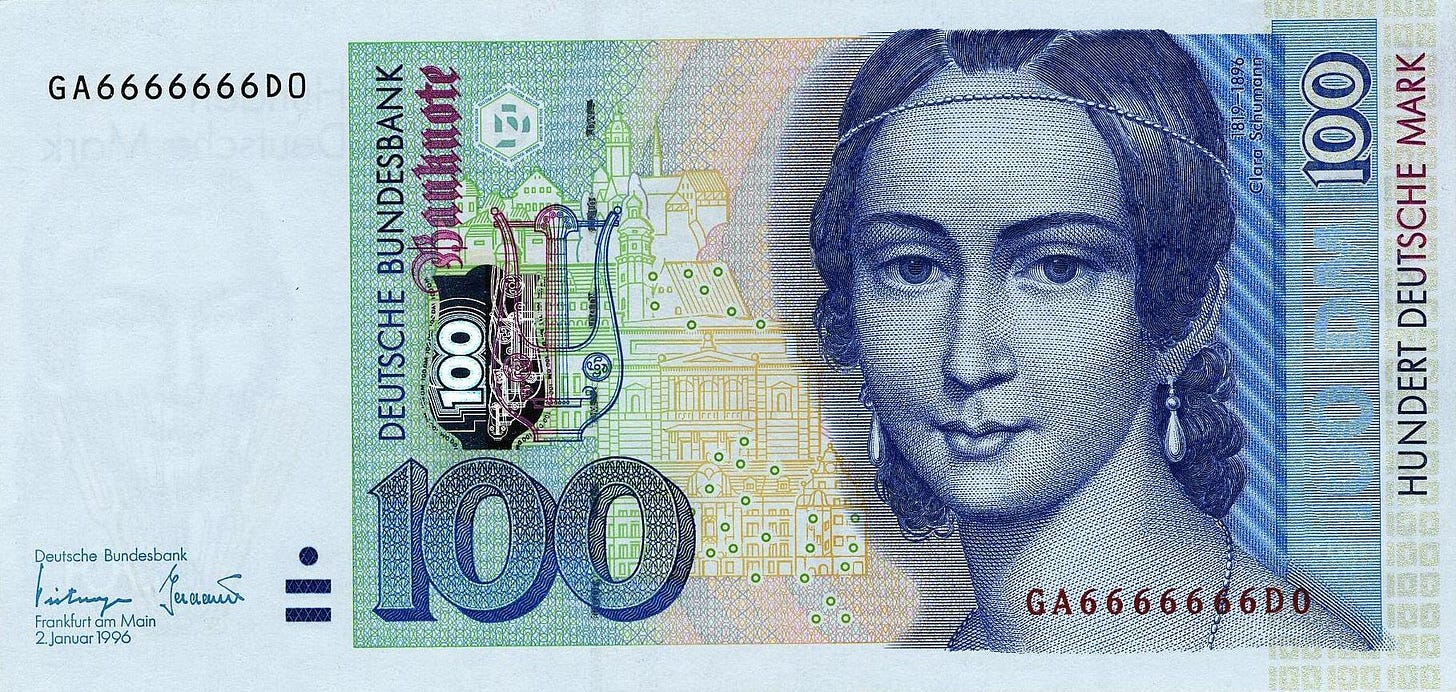

Although the number of compositions Clara produced grew smaller over time, due to her increasing demands as concert artist, wife, and mother, she managed to have the majority of her music published — an enormous achievement for any composer, let alone a woman in mid-19th-century Germany. And despite her music falling into the shadows for nearly a century after her death in 1896, Clara's work largely wasn't marginalized during her lifetime.

In fact, it was celebrated by audiences and critics alike, as was the case with her Piano Concerto.

Clara's only surviving orchestral work, the Piano Concerto evolved from a one-movement concert piece (Konzertsatz) she began composing at the age of 13. As a piano soloist on the rise, she would have been expected to perform improvisations and works of her own making, so the Konzertsatz ultimately served as both a statement of creative expression and a star-making showpiece.

Clara eventually expanded the work into a three-movement concerto, using the Konzertsatz material for the final third. She orchestrated the first and second movements and made comprehensive edits to Robert's original orchestration of the Konzertsatz. Following the full concerto's 1835 premiere, which featured Clara as soloist accompanied by Leipzig's Gewandhaus Orchestra under the baton of Felix Mendelssohn, the work received many performances throughout Clara's career — including an 1837 concert in which she was summoned to the stage for a record four curtain calls.

Groundbreaking for its time, the concerto not only carries the emotional intensity and operatic melodicism of the new Romantic style, but its structure is also inventive: three uninterrupted movements, made architecturally cohesive by the use of shared melodies woven across each movement. And while the concerto teems with flashy displays of virtuosity in its outer movements, it includes none of the improvised cadenzas made standard by composers like Mozart and Beethoven. Rather, the technical fireworks are baked into the work's character, with flights of filigreed fancy across the keyboard alternating with pulsating passages of thunderous chords.

As expected in a composition meant to showcase the soloist's superpowers, the piano doesn't converse with the orchestra so much as tower over it. Still, Clara manages to capture moments of quietly mesmerizing beauty, especially in the central Romanze. As the drama of the first movement subsides and the first four notes of its main theme echo slowly in the distance, the solo piano spins them into a new melody of melancholic beauty.

Clara silences the orchestra for this movement, giving the piano room to deliver a hushed aria that becomes increasingly ornate and impassioned. A solo cello later enters the scene, taking the piano's melody of grace and romantic longing to new heights in its searingly expressive top register. This tender dialogue between piano and a lone cello, unheard of at that time in a concerto for piano and orchestra, would inspire similar moments of intimate beauty in the music of the two men closest to Clara's heart. Both Robert's Piano Concerto and Brahms's Second Piano Concerto feature prominent cello solos in their respective slow movements.

So why is this youthful concerto the only large-scale work to have flowed from Clara's pen? Of course there are societal reasons: The Schumanns loved each other deeply and tenderly supported each other's work, but Robert still considered the duties of wife and mother to be Clara's main priorities — though he remained conflicted about the impact of household responsibilities on Clara's creativity. Three years into their marriage, Robert confessed:

"To have children and a husband who is always living in the realms of imagination do not go together with composing. She cannot work at it regularly, and I am often disturbed to think how many profound ideas are lost because she cannot work them out."

Clara herself was ambivalent about the role of composition in her career. On one hand, she wrote about the transporting quality of composition:

"There is nothing that surpasses creative activity, even if only for those hours of self-forgetfulness in which one breathes solely in the world of sound."

But she also confessed to the artist's trademark sense of inadequacy and imposter syndrome, fueled by the misogyny of her time:

"I once believed I had creative talent, but I have given up this idea. A woman must not wish to compose — there never was one able to do it. Am I intended to be the one? It would be arrogant to believe that."

Look deeper, however, and we see in Clara's letters and diary entries evidence that societal expectations weren't the only reason for her eventual silence as a composer. Being a creator of music, as opposed to an interpreter, wasn't necessarily a passion of hers. Rather than chasing a creative muse of her own, she largely composed out of a sense of duty — to her overbearing father during her education, to her sensitive husband during their marriage, and to the hungry concert-going public early in her career, who expected to hear pianists perform their own works.

We can trace how Clara's departure from the world of composition overlapped with major changes in those audience expectations. As attitudes shifted in the final decades of the 19th century, with soloists increasingly called upon to deliver immaculate readings of works by established (and often dead) composers rather than present their own music, Clara had a diminishing need to continue composing.

But that never stopped her from performing her music: At nearly every concert until she retired from the stage at 72, at least one work on the program bore the byline Clara Schumann.

Take a listen …

What was your experience listening to Clara's rapturous aria for piano and cello? I want to know! Be sure to leave a comment below or reply to this email. (And if you enjoyed your time here today, would you ever so kindly tap that little heart below? 👇🏼)

Thank you for reading Shades of Blue! This newsletter is free, but paid subscribers help support the 20+ hours of research, writing, editing, and production that goes into every essay. If you look forward to reading Shades of Blue, please consider becoming a paid subscriber …

… or make a one-time donation through Buy Me a Coffee:

What an incredible life story. She is an inspiration, especially in the way she was so inventive, even avant-garde, and continued to play and compose despite all her responsibilities. Thanks for bringing this story and music to us, Michael! 💙

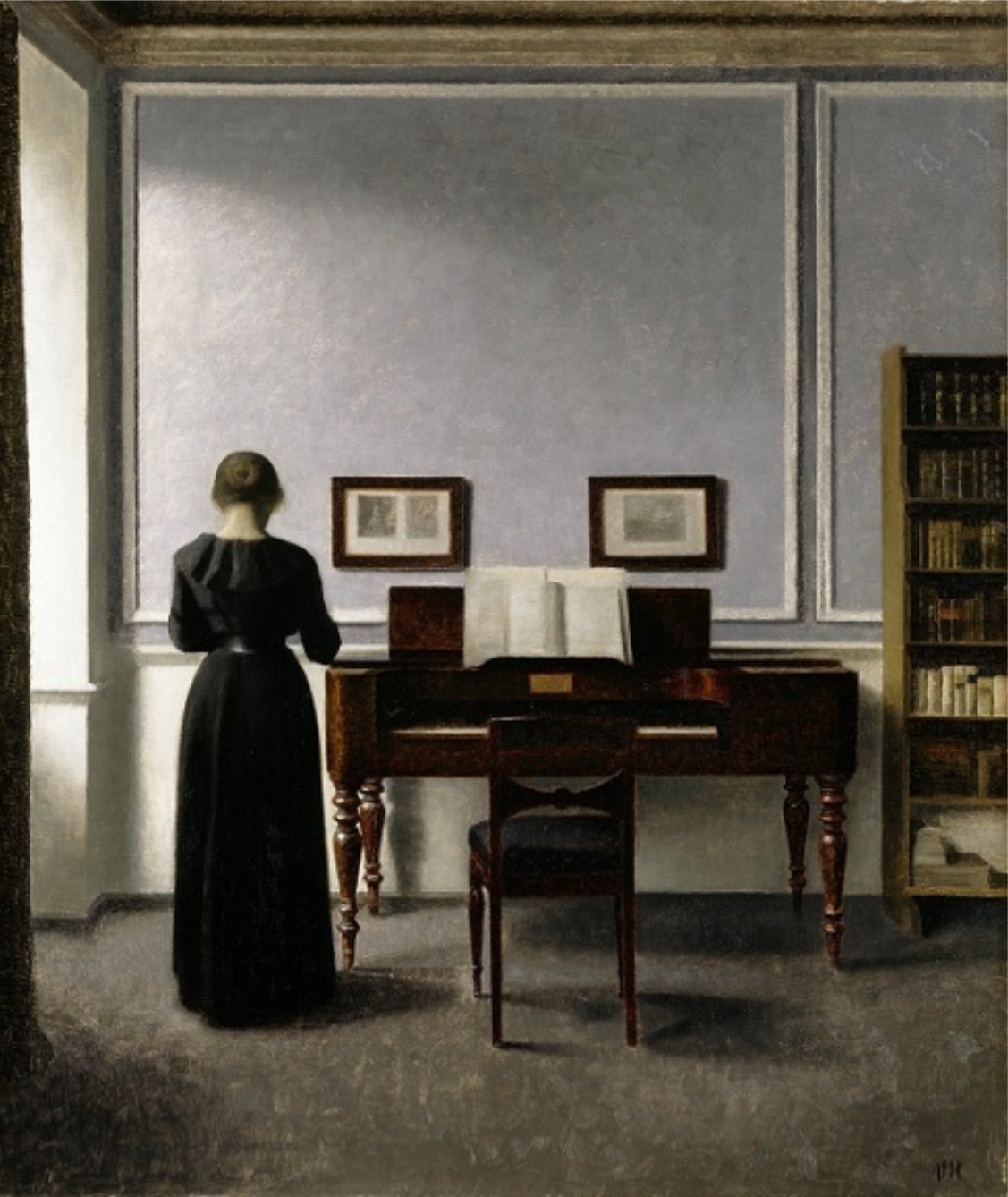

A marvellous choice for an article falling around International Women's Day. I find this a really positive story. It would be easy to see only the negatives, but this is a nuanced story. Apart from the obvious difficulties that a woman of her era faced, she received recognition during her lifetime and ended up on a bank note which is fantastic. Thank you Michael, I shall now listen, and judging by everything you send us, it will be tremendous. I love the painting too.