Claude Debussy / Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun

Be transported to a garden of earthly delights in an orchestral fever dream of sensual bliss.

Imagine picking up a flute for the first time. After admiring the way light dances across its glistening metallic body, you slowly raise the instrument's head joint to your face. You fill your lungs with a deep well of air and gently contort your mouth into an embouchure resembling both a smile and a sob. Finally, you exhale, producing a steady stream of air that cuts across the flute's tone hole to manifest sound.

That sound, produced without pressing any of the flute's keys, is a C-sharp: a raspy, nebulous note that sits between the instrument's burnished lower register and its silvery soprano. In all its woolen breathiness, this C-sharp reminds us that the flute — alongside voices and drums — is one of the oldest sounds of human musical expression. For thousands of years, we've channeled these instruments to pay homage to sun and moon, profess love and sorrow, and express awe at the vast expanse of natural beauty around us.

And it's with this C-sharp, both primal and otherworldly, that Claude Debussy opens his Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun (Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune) — an orchestral fever dream that transports us to Arcadian meadows of the distant past, to an irresistible mythological world where satyrs, nymphs, and nature commune in exquisite harmony.

Debussy took direct inspiration for his Prelude from an 1876 poem, L'Après-midi d'un faune, by the French Symbolist writer Stéphane Mallarmé. Led by Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine, and Mallarmé, the Symbolist movement rejected Realism and standard forms of poetry, seeking instead to create writing that swims in subliminal emotions, explores dream-like states of subconscious being, and embraces the occult and macabre. The aesthetic goal for the Symbolists, in the words of Paul Valéry, was to "unite the world around us with the inner world that haunts us."

Debussy held the same aspirations for his music, and few compositions in his spectacular body of work embody those ideals quite like his Prelude. In just 10 minutes, the tone poem's 110 bars of music — the same number of lines as in Mallarmé's poem — connect us to an ancient time and place that, although unfamiliar to our conscious minds and perceptions of reality, is hardwired in our DNA.

As hypnotic and radical as Debussy and Mallarmé's individual works are, they set a scene that is astoundingly simple. In a rocky meadow baking in the sweltering heat of summer, a Faun — half-man, half-goat — awakes from a mid-day nap. As he yawns and stretches each limb, he recalls an episode earlier that morning when he encountered a group of nymphs searching for a bathing pool. Games of flirtation and seduction left the Faun heartbroken after the nymphs fled the scene. Rather than pursue them, the Faun returned to his rock and entered a state of blissful slumber where he could realize his dreams of erotic ecstasy.

The heavy heat, the mix of drowsiness, lust, and puckish play — Debussy weaves them all into the haze of his luminous, melancholy music from the opening bar. The solo flute's mysterious C-sharp lazily unfolds into a breathtakingly beautiful melody before giving way to the orchestra's first entrance: a bewildering chord in the woodwinds, over which an ethereal harp floats up and down its strings while a pair of French horns emit a series of yawns and groans.

Then ... silence.

For nine beats, we're met with a complete absence of sound that leaves us unmoored, dizzy. The woodwinds then echo their macabre chord, the harp once again shimmers, and the horn calls make way for the return of the Faun's flute, this time intoning its flights of fancy over a bed of trembling strings.

The music of Debussy's Prelude may feel pulseless and improvisatory, but those sonic special effects are made possible by the composer's exacting approach to rhythm, sonority, and orchestral color. From the playful, spinning clarinet figure that marks the beginning of the Faun's dance with the nymphs, to the heartbreaking chorus of longing and lust sung by the woodwind instruments, Debussy seamlessly sustains his hypnotic musical dreamscape until the music gradually decays into reverential silence. With the delicate tinkling of a pair of antique cymbals, the Faun surrenders to sleep just as we return to reality.

Although Mallarmé had initial reservations about Debussy setting his poem as a purely instrumental work, he was immediately awed by the music's power to paint his words. He lavished praise on Debussy, saying:

"This music prolongs the emotion of my poem and sets its scene more vividly than color. … Your illustration of L'Après would present no dissonance with my text, unless to go further, indeed, into the nostalgia and the light, with finesse, with malaise, with richness."

Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun has been one of my musical happy places for most of my life, but that connection to the work has only grown stronger in recent years. As the effects of our climate catastrophe continue to invade our everyday lives — especially this summer, as wildfire smoke turns the sky into the color of copper pennies and the very air we need to live becomes a hazard to our bodies — the Prelude serves as my direct portal to a place where nature thrives and is revered, where I can tap into its divinity and the profound sense of awe and reverie it inspires.

It's also my favorite example of the way one work of art can be expanded upon, reinterpreted, even transformed by artists of different creative disciplines. First, Mallarmé's poem inspires music from Debussy that breaks away from the traditional forms, rhythms, and harmonies that had dominated European music for two centuries. Then, Debussy's radical music inspires a radical sea change in the ballet world, thanks to Vaslav Nijinsky and the Ballets Russes.

In 1912, Sergei Diaghilev chose Debussy's Prelude as the basis for a new work for his groundbreaking dance company, whose performances had become the hottest ticket in Paris. Diaghilev's mission was to refashion a stuffy form of entertainment reserved for court theaters into a living, breathing art form — one that not only showcased the latest trends in the visual arts and music, but also expressed a raw, vibrant sensuality through dance.

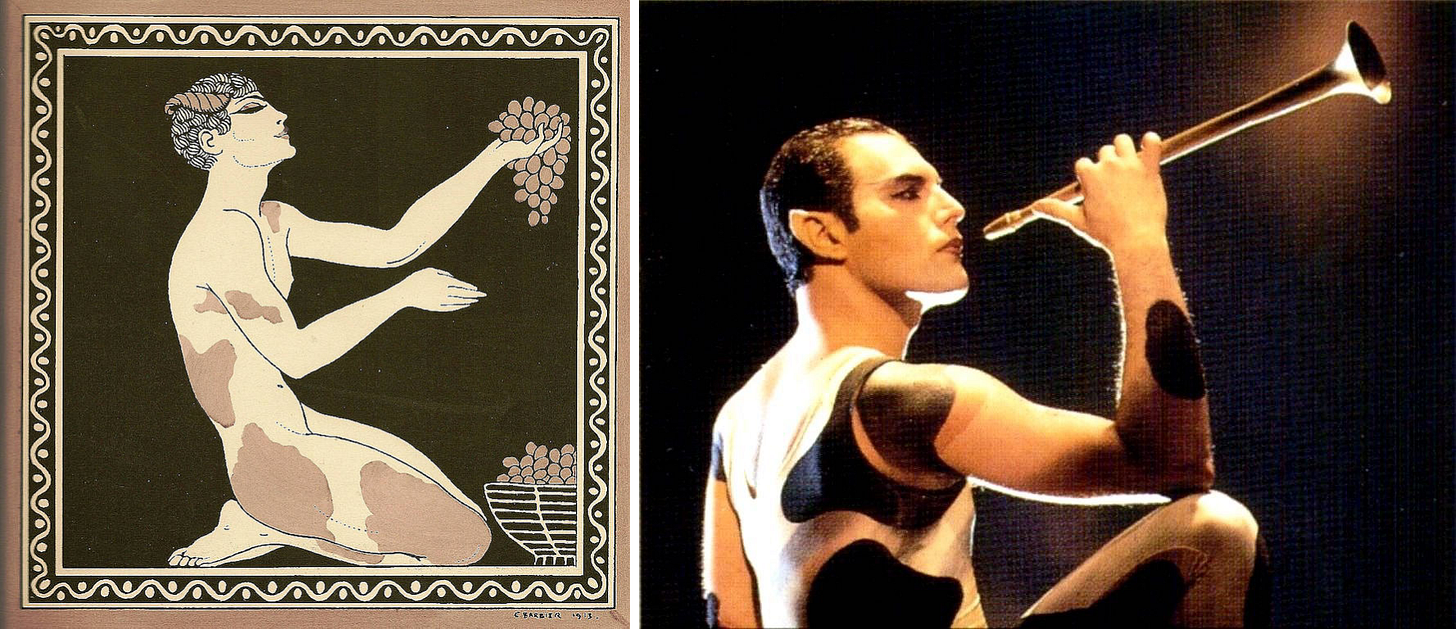

For his Faun, Diaghilev turned to the Ballets Russes' star dancer (and his lover at the time), Vaslav Nijinsky, who astounded audiences with a signature style that fused grace and elegance with feline feats of physical prowess. Although Nijinsky had never choreographed a ballet before, Diaghilev intimately knew the rebellious ideas his star had about modernizing ballet. Instead of relying on standard dance techniques, Nijinsky turned to ancient Greek vases and Assyrian frescoes as inspiration for his ballet, which featured long-held stylized poses, frequent pauses in the dancers' motion, and choreography that didn't directly relate to the meter of the music.

But most of all, Nijinsky unleashed a shocking eroticism in his Faun that was further accentuated by his revealing fig leaf body stocking designed by the artist Léon Bakst, who also created the ballet's lushly pastoral stage design.

The Parisian audience at the ballet's premiere wasn't prepared for this new type of dance and its unbridled sexuality. Eliciting cheers, catcalls, and pearl-clutching once the curtain came down — provoked by the ending, in which Nijinsky graphically aroused himself atop a silk scarf the nymphs left behind — the new ballet proved a succès de scandale. The company performed the ballet to sold-out crowds for the remainder of the company's 1912 season.

Nijinsky's Faun would go on to become an emblem of artistic, political, and sexual freedom throughout the 20th century. Rudolf Nureyev performed the ballet to great acclaim in the years following his defection from the Soviet Union in 1961. And in Queen's video for "I Want to Break Free," Freddie Mercury imagines himself as Nijinsky's Faun in the video's central fantasy sequence. Accompanied by dancers from London's Royal Ballet, Mercury dons Bakst's body stocking in an orgiastic scene of earthly delights that transcends the conservatism of Margaret Thatcher's deeply homophobic Britain.

More than a century after the ballet's premiere, Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun continues to inspire and enchant as a symbol of radical freedom and an intense longing for a world of Arcadian beauty that lies well outside the reach of our conscious mind. What is the hold this marriage of poetry, music, and movement has over us? Perhaps it's because we can see ourselves reflected in Mallarmé, Debussy, and Nijinsky's Faun: feral and feisty and exquisite and expressive, unhurriedly navigating a hazy world, longing for communion, longing for moments of quiet ecstasy.

Take a listen ...

I'd love to hear about your experience with Debussy's Prelude, and where the music of the Faun's flute takes you. (And be sure to witness Nureyev's hypnotizing performance as the Faun in this 1981 realization of Nijisnky's ballet.)

What touches you most? The pastoral calm of the setting, the smoldering sensuality that lives beneath the glossy surface of Debussy's score, the gentle ebb and flow of the music itself — or something completely different? Be sure to let me know in the comments.

If you enjoyed this journey through Debussy's Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, would you let me know by tapping on that heart below? 👇🏼

Oh man, I took one music appreciation class in college and this composition was a highlight. Unforgettable! I may have been Athens, GA's most enthusiastic Debussy fan in the late 90s. Never knew the bit of history about the Ballet Russes performance or the Queen reference! So cool.

Thanks for another pleasurable read, Michael. I had no idea that Nureyev had also performed this ballet.

I especially enjoyed your evocation of Nijinsky, Diaghilev, and the heady atmosphere of artistic ferment that was Paris circa 1912, when groundbreaking artistic performances - in ballet, music, painting, or even literature - could provoke unfeigned outrage. It's so interesting to look back at that time from the vantage point of our jaded postmodern 21st-century culture.

What touches me most about this piece of music? I suppose it's the work's modernity - its apparent formlessness, and what you aptly describe as Debussy's "exacting approach to rhythm, sonority, and orchestral color." It's evocative to me of that exciting and risky period in modernist art and culture - stretching from the early 1900s through to the 1930s - which saw the emergence of so many formal innovations all across the arts.

Maurice Ravel is another favourite of mine from this period, and reading your account of the uproar caused by Nijinsky's performance put me in mind of the furore surrounding Ravel's ballet "Daphnis et Chloé." There's a wonderful minimalist novel titled Ravel by a writer named Jean Echenoz, which I think you'd enjoy as it also recreates this period in modern music.