Revisiting a mythological fever dream of lust and longing

Claude Debussy / Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun

Hi, everyone,

I'm currently chin-deep in research for a series of program essays I'm writing for the Britt Festival Orchestra's summer season. So today I'm revisiting a piece I published in the earliest days of Shades of Blue, on Claude Debussy's hypnotic Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun.

Debussy's Prelude is a work I've held close to my heart for most of my life. Not only is the music a direct portal to a place of Arcadian beauty, where nature is revered for its dazzling divinity — it also stands as an emblem of artistic, political, and sexual freedom, thanks to a trio of groundbreaking artists I adore: Vaslav Nijinsky, Rudolf Nureyev, and Freddie Mercury. Enjoy!

— Michael

Imagine picking up a flute for the first time. After admiring the way light dances across its glistening metallic body, you slowly raise the instrument's head joint to your face. You fill your lungs with a deep well of air and gently contort your lips into an embouchure that somehow resembles both a smile and a sob. Finally, you exhale, and a steady stream of air cuts across the flute's tone hole to manifest sound.

That sound, produced without pressing any of the flute's keys, is a C-sharp: a raspy, nebulous note that sits between the instrument's burnished lower register and its silvery soprano. In all its woolen breathiness, this C-sharp reminds us that the flute — alongside voices and drums — is one of the oldest sounds of human musical expression. For thousands of years, we've channeled these instruments to pay homage to sun and moon, profess love and sorrow, and express awe at the vast natural beauty around us.

And it's with this C-sharp, both primal and otherworldly, that Claude Debussy opens his Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun (Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune) — an orchestral fever dream that transports us to Arcadian meadows of the distant past, to an irresistible mythological world where satyrs, nymphs, and nature commune in exquisite harmony.

Debussy took direct inspiration for his Prelude from an 1876 poem, L'Après-midi d'un faune, by the French Symbolist writer Stéphane Mallarmé. Led by Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine, and Mallarmé, the Symbolist movement rejected Realism and standard forms of poetry, seeking instead to create with their writing new worlds that swim in subliminal emotions, explore dream-like states of subconscious being, and embrace the occult and macabre. The aesthetic goal for the Symbolists, in the words of Paul Valéry, was to "unite the world around us with the inner world that haunts us."

Debussy held the same aspirations for his music, and few compositions in his spectacular body of work embody those ideals quite like his Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun. Over its 10 minutes, the tone poem's 110 bars of music — the same number of lines as in Mallarmé's poem — connect us to an ancient time and place that, although unfamiliar to our conscious minds and perceptions of reality, is hardwired in our DNA.

As hypnotic and radical as Debussy and Mallarmé's individual works are, they set a simple scene. In a rocky meadow baking in the sweltering heat of summer, a Faun — half-man, half-goat — awakes from a midday nap. As he yawns and stretches each limb, the Faun recalls an episode earlier that morning when he encountered a group of nymphs searching for a bathing pool. His games of flirtation and seduction frighten the nymphs and cause them to flee the scene, leaving the Faun heartbroken. Rather than pursue them, he returns to his rock and surrenders to a state of blissful slumber where he realizes dreams of erotic ecstasy.

The heavy heat, the mix of drowsiness, lust, and puckish play — Debussy weaves them all into the haze of his luminous, melancholy music from the opening bar. The solo flute's mysterious C-sharp lazily unfolds into a breathtakingly beautiful melody before giving way to the orchestra's first entrance: a bewildering chord in the woodwinds, over which an ethereal harp floats up and down its strings while a pair of French horns emit a series of listless groans.

Then ... silence.

For nine beats, we're met with a complete absence of sound that leaves us dizzy, unmoored. The woodwinds then echo their macabre chord, the harp once again shimmers, and the horn calls make way for the return of the Faun's flute, its flights of fancy now cushioned by a bed of trembling strings.

The music of Debussy's Prelude may feel pulseless and improvisatory, but those sonic special effects are made possible by the composer's exacting approach to rhythm, sonority, and orchestral color. From the playful, spinning clarinet figure that marks the beginning of the Faun's dance with the nymphs, to the heartbreaking chorus of longing and lust sung by the woodwinds, Debussy seamlessly sustains his hypnotic musical dreamscape until the music gradually decays into reverential silence. With the delicate tinkling of a pair of antique cymbals, the Faun surrenders to sleep and we return to reality.

Although Mallarmé had initial reservations about Debussy setting his poem as an instrumental work, he was immediately awed by the music's power to paint his words. He lavished praise on Debussy, saying:

"This music prolongs the emotion of my poem and sets its scene more vividly than color. … Your illustration of L'Après would present no dissonance with my text, unless to go further, indeed, into the nostalgia and the light, with finesse, with malaise, with richness."

Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun has been one of my musical happy places for most of my life, but that connection to the work has only grown stronger in recent years. As the effects of our climate catastrophe continue to invade our everyday lives — especially during the summer months, when wildfire smoke turns the sky into the color of copper pennies and the very air we need to live becomes a hazard to our bodies — the Prelude serves as my direct portal to a place where nature thrives and is revered, where I can tap into its divinity and the profound sense of wonder and reverie it inspires.

It's also my favorite example of the way one work of art can be expanded upon, reinterpreted, even transformed by artists of different creative disciplines. First, Mallarmé's poem inspires music from Debussy that breaks away from the traditional forms, rhythms, and harmonies that had dominated European music for two centuries. Then, Debussy's radical music inspires an equally radical sea change in the ballet world, thanks to Vaslav Nijinsky and the Ballets Russes.

In 1912, Sergei Diaghilev chose Debussy's Prelude as the basis for a new work for the groundbreaking dance company he founded, whose performances had become the hottest ticket in Paris. Diaghilev's mission was to refashion ballet, formerly a stuffy form of entertainment reserved for court theaters, into a living, breathing art form — one that not only showcased the latest trends in the visual arts and music, but also expressed a raw, vibrant sensuality through dance.

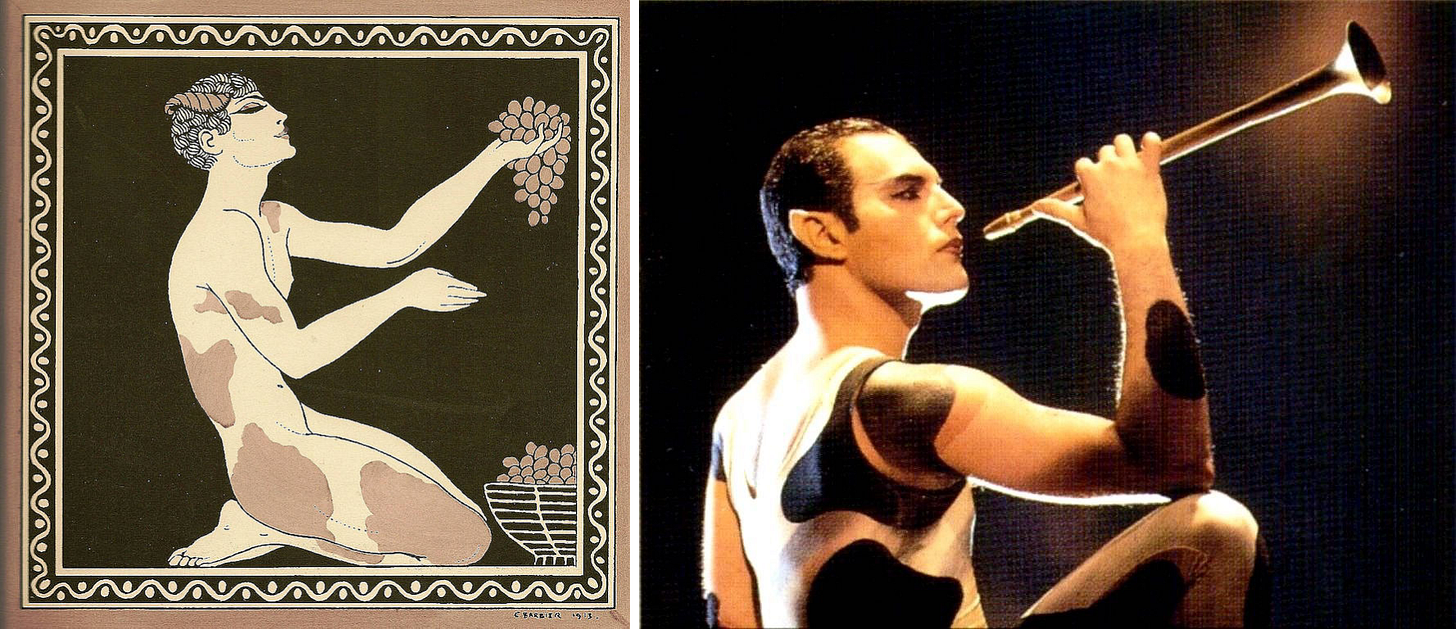

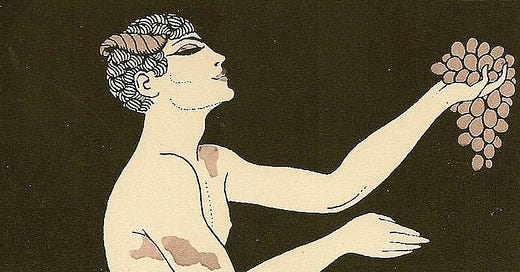

For his Faun, Diaghilev turned to the Ballets Russes' star dancer (and his lover at the time), Vaslav Nijinsky, who astounded audiences with a signature style that fused grace and elegance with feline feats of physical prowess. Although Nijinsky had never choreographed a ballet before, Diaghilev intimately knew the rebellious ideas his star had about modernizing ballet. Instead of relying on standard dance techniques, Nijinsky turned to ancient Greek vases and Assyrian frescoes as inspiration for his ballet, which featured long-held stylized poses, frequent pauses in the dancers' motion, and choreography that didn't directly relate to the meter of the music.

But most of all, Nijinsky unleashed a shocking eroticism in his Faun that was further accentuated by his revealing fig-leaf body stocking designed by the artist Léon Bakst, who also created the ballet's lushly pastoral stage design.

The Parisian audience at the ballet's premiere wasn't prepared for this new type of dance and its unbridled sexuality. Eliciting cheers, catcalls, and pearl-clutching once the curtain came down — provoked by the ending, in which Nijinsky graphically aroused himself atop a silk scarf the nymphs left behind — the new ballet proved a succès de scandale. The company performed the work to sold-out crowds for the remainder of the company's 1912 season.

Nijinsky's Faun would go on to become an emblem of artistic, political, and sexual freedom throughout the 20th century. Rudolf Nureyev performed the ballet to great acclaim in the years following his defection from the Soviet Union in 1961. And in Queen's video for "I Want to Break Free," Freddie Mercury imagines himself as Nijinsky's Faun in the video's central fantasy sequence. Accompanied by dancers from London's Royal Ballet, Mercury dons Bakst's body stocking in an orgiastic scene of earthly delights, a pointed rebuke of the conservatism of Margaret Thatcher's deeply homophobic Britain.

More than a century after the ballet's premiere, Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun continues to inspire and enchant as a symbol of radical freedom and an intense longing for a world of Arcadian beauty that lies well outside the reach of our conscious mind. What is the hold this marriage of poetry, music, and movement has over us? Perhaps it's because we can see ourselves reflected in Mallarmé, Debussy, and Nijinsky's Faun: feral and feisty and elegant and expressive, unhurriedly navigating a hazy world, longing for communion, longing for moments of quiet ecstasy.

Take a listen ...

I'd love to hear about your experience with Debussy's Prelude, and where the music of the Faun's flute takes you. What touches you most? The pastoral calm of the setting, the smoldering sensuality that lives beneath the glossy surface of Debussy's score, the gentle ebb and flow of the music itself — or something completely different? Be sure to leave a comment below or reply to this email.

(And if you enjoyed your time here today, would you ever so kindly tap that little heart below? 👇🏼)

Thank you for reading Shades of Blue! This newsletter is free, but paid subscribers help support the 20+ hours of research, writing, editing, and production that goes into every essay. If you look forward to reading Shades of Blue, please consider becoming a paid subscriber …

… or make a one-time donation through Buy Me a Coffee:

I watched Nureyev perform Nijinsky's choreography of "L'Après-midi d'un faun" a few weeks back and was surprised by how (comparatively) tame it seemed given the scandal! Maybe it's just millennial, corrupted sensibilities.

This is a beautiful piece, Michael, and I love your alliteration! I stumbled on the Symbolist Manifesto in December and paste the link here for anyone who's interested: https://enjoymutable.com/home/thesymbolistmanifesto

Take care,

Sophia

What a beautiful article. Just lovely to get the background on this enchanting piece of music, and fascinating to hear that a pop video I recorded on a VHS tape in 1984 is connected with both this and the Royal Ballet. How typical of Freddie to incorporate something like this into his work. I never realised the significance of that fabulous choreography in I Want to Break Free. Thanks very much Michael. (Oh, and Nureyev. Divine. And with Fonteyn...✨)