Erich Korngold / Violin Concerto

Embedded within a gentle serenade lies one composer's story of displacement, loss, and longing for a home that exists only in memory.

One of the most gratifying aspects of writing this newsletter is hearing all of your reactions to the music I share here in real time — especially the works included in Shades of Blue's Melancholy Mixtape series. Because unlike the deep-dive essays, where the human story behind each work illuminates its emotional landscapes, in Mixtape posts, the music alone serves as your guide to cultivating calm, connection, and healing.

Each Mixtape collection includes several works, and I love hearing which ones you're drawn to, the moments that immediately soften the heart. More often, people speak to different works, but that wasn't the case in January's Melancholy Mixtape. The majority expressed love for one particular selection, the Romance at the center of Erich Wolfgang Korngold's Violin Concerto — as well as an amazement that they hadn't ever heard of this composer. How could someone who writes music this ravishing have remained a mystery for so long?

While it's clear Korngold's gentle serenade for solo violin and orchestra pulls at our heartstrings all by itself, this is a case where the story surrounding the work — and the story of Korngold himself — adds profound depth to our experience of his music.

So whether you were moved by the work back in January, or you're hearing it for the first time today, here's the story of longing and loss, war and displacement that fueled Korngold's melancholy romance.

Even if you don't recognize the name Erich Wolfgang Korngold, you've already encountered his important legacy in the world of cinema. If your childhood was shaped by John Williams's music for Star Wars, if Gotham City is synonymous with Danny Elfman's Batman march, or you're immediately transported to Middle-earth through Howard Shore's Lord of the Rings scores, then you have Erich Korngold to thank.

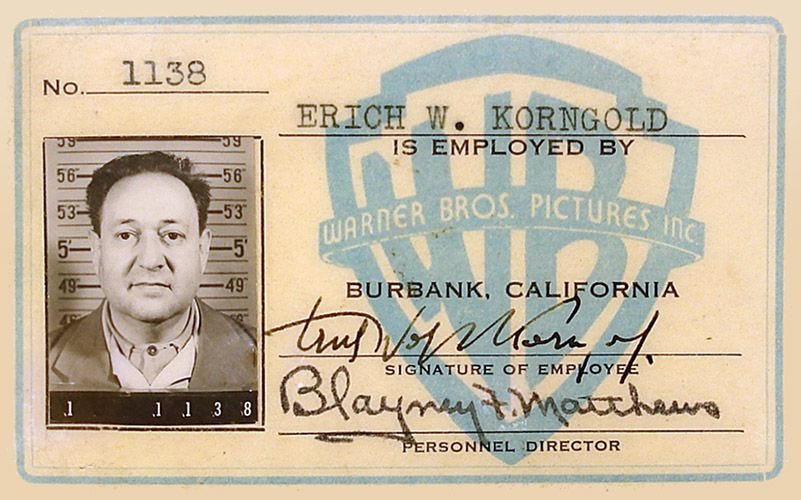

One of the pioneers of film scoring, the Austrian composer's lush harmonies and operatic melodies helped define the sound of Golden Age Hollywood. Between 1934 and 1946, he composed 20 scores — two of which garnered him Academy Awards — for Warner Brothers films starring the biggest names in the industry, from Errol Flynn and Claude Rains to Bette Davis and Olivia de Havilland.

But Erich never intended to spend so much time in the business of making movies. Rather, his work in Hollywood was primarily an act of survival and political protest.

By the time he set foot on Californian soil in 1934, Erich had become one of the most popular composers in the Austro-German world — a prodigy of Mozartian proportions in fin de siècle Vienna, where composers like Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss walked the streets like modern-day Prometheuses. He premiered his first major work, the ballet Der Schneemann (The Snowman), at the age of 11, and by his 24th birthday he had enjoyed successful runs of four operas.

Despite his enormous popularity in Vienna, Erich was lured to the bright lights of Hollywood by the director Max Reinhardt, who engaged the composer to contribute music to his big-screen adaptation of Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream. Erich's enormous talents as a composer, pianist, and conductor led to immediate demand for his work, and he penned six film scores over the next three years as he journeyed between Los Angeles and his home in Vienna.

But in 1938, Erich's life — and the lives of all Jewish people in Austria — came under tremendous threat. With Hitler and his Third Reich on the rise, the Korngold family faced untold dangers. "We thought of ourselves as Viennese," the composer later wrote. "Hitler made us Jewish."

Seeing the writing on the wall, Erich accepted an offer to score the swashbuckling film The Adventures of Robin Hood and made his way back to Hollywood. Only this time, his family, including his parents and brother, also made the transatlantic journey to Los Angeles, where they found safe haven just before the Nazis invaded Austria.

The composer weathered both deep depression and seething anger as he worked on his Robin Hood score. In defiance of the devastation German forces wrought at home, Erich vowed to give up composing everything but film music until "that monster" Hitler was defeated.

He had always referred to films as "operas without singing," so as Erich waited out the war in America, he made the most of his film work. The melodramatic romances and fantastical adventure stories he brought to life through sound proved a vital escape from the horrors abroad and the challenges of navigating life as a refugee. His wife, Luszi Sonnenthal Korngold, later shared that by comparing a film's story to an opera libretto, her husband "was able to convince himself of the perhaps deliberate delusion that he was creating an operatic work."

But after 11 years in Hollywood, the novelty of composing for the big screen faded for Erich. He was grateful for the steady income he received as a Warner Brothers employee — funds he used to support fellow refugees who had fled Europe — but he was increasingly frustrated by the lack of creative freedom and the studio executives who prioritized profit over artistic expression.

As the bells tolled on May 8, 1945, celebrating Germany's formal surrender to the Allied powers, Erich was ready to leave his work as a film composer behind and return to the concert stage.

For his first postwar statement, Erich chose one of the most beloved forms in classical music: the violin concerto, which had achieved great popularity in the 19th century thanks to the poetic takes of Ludwig van Beethoven, Johannes Brahms, and Felix Mendelssohn.

Erich's concerto, it turned out, proved a perfect synthesis of the composer's experience with opera and film music. In fact, music from four of his film scores made their way into his Violin Concerto — a quasi-cinematic adventure of wide-ranging emotion, with the violin serving as the matinee idol at the center of the story.

At the heart of the concerto is a sweet serenade entitled Romance, built around a theme Erich had written for Anthony Adverse, a rags-to-riches tale of love and loss set in the tumultuous years of the Napoleonic Wars. The theme first occurs in the film when the protagonist Anthony (Frederich March) and his love interest Angela (Olivia de Havilland) discuss their hopes and dreams for a lifetime together — a future that ultimately never comes to pass, as Fate relentlessly turns her wheel of fortune to keep the pair apart and prevent love from fully blossoming.

The violin sings these amorous melodies with an affectionate lyricism as it journeys from hushed and intimate confessions to rich, burnished expressions of passion. This is music that merges past and future, nostalgia and desire, as the violin floats above a bed of feathery strings and harp, weeping woodwinds, and the evocative sounds of celeste and vibraphone, two percussion instruments whose reverberant bells move through us like a mystical entity unlocking long-held memories.

A heart attack put Erich's plans to return to Europe on hold, and when he finally arrived in Austria in 1949, it wasn't the homecoming he had imagined. Seeing the destruction done to Vienna was difficult to confront, friends who had remained in Austria throughout the war were hostile that he had left, and performances of his works were poorly attended. A second visit in 1954 solidified what he had feared: Audiences no longer had an appetite for his music.

In the aftermath of a near-apocalyptic war, composers had begun to create new musical languages to express the charred world around them. Even in Vienna, the site of Erich's biggest artistic triumphs, his evocative, hyperexpressive music was deemed passè, too rooted in the grand Romantic tradition that had dominated the city's cultural scene at the turn of the century. Despondent, he left Austria believing that his music would be forgotten forever.

Erich spent his final years as a naturalized U.S. citizen living in Los Angeles's Toluca Lake neighborhood, where he composed a handful of orchestral works, a string quartet, and six songs. But none of those postwar works has become more popular in our century than his Violin Concerto, music that, despite the glamorous sheen of its Hollywood origins, expresses Erich's heartbreaking longing — for the Vienna that no longer existed but in memories, for the years stolen from him by a murderous regime, for the adoration his music once received.

In November 1957, Erich Wolfgang Korngold died at the age of 60, his body interred at Hollywood Forever Cemetery — more than 6,100 miles from his beloved Vienna — where he's protected from the blistering So Cal sun by the shade of a lone cypress tree.

Take a listen …

Baiba Skride, violin Gothenburg Symphony Santtu-Matias Rouvali, conductor

I'd love to hear about your experience with Korngold's cinematic serenade. Let me know — either by replying to this email or sharing a comment below.

(And if you enjoyed your time here today, how about tapping that little heart below? 👇🏼)

Thank you for reading Shades of Blue!

This newsletter is free, but paid subscribers directly support the 20+ hours of research, writing, editing, and production that go into every essay. If you look forward to reading Shades of Blue when it arrives in your inbox, please consider becoming a paid subscriber …

Or if you'd like to buy me a coffee as a token of thanks for this post, you can make a one-time donation to keep this newsletter going …

Everything about how his life unfolded in the end makes me so sad 💙 Clearly he was born in the wrong age (tho I’m sure so many were thrilled to experience his music during their lifetimes!) This piece is magnificent… so many colors. In that final third, I picture him walking through Vienna after the war. A beautiful disaster. Thank you for honoring his name and music here on this corner of the internet, especially for those of us who’d never learned about his pivotal influence on our beloved film scores!

Hey, thank you for this tribute to Korngold, and for weaving together the themes of his life and experience into your narrative so adroitly.