Franz Schubert / Piano Trio No. 1

A symphony in miniature, written in a language of friendship lovingly etched into every measure.

This time of year, as Halloween creeps closer on the calendar, a craving for gothic vampire films consumes me. If I'm in the mood for opulent sets and costumes, I'll turn to Bram Stoker's Dracula and the tour de force performance from Gary Oldman. If I want a heavy dose of homoeroticism, I'll revisit Neil Jordan's campy, blood-soaked adaptation of Anne Rice's Interview with the Vampire. And for a gritty, modern take on the vamp genre, I have to go with The Hunger.

Starring Catherine Deneuve, David Bowie, and Susan Sarandon, the 1983 cult classic ticks a lot of aesthetic boxes for me — including the heavenly vision that is Deneuve in Dynasty-style power suits, shadowy cinematography that evokes the Italian Baroque, and a sweaty opening sequence that pulsates with Bauhaus's goth anthem "Bela Lugosi's Dead." But the aspect of The Hunger I love most: Miriam and John, the centuries-old vampire lovers played by Deneuve and Bowie, spend their days posing as an elegant Manhattan couple who teach — what else? — classical music.

Early in the film, it's time for a lesson with one of their pupils, a teenage violinist named Alice. The three assemble in Miriam and John's spacious townhouse parlor to rehearse the slow movement of Franz Schubert's Piano Trio No. 1. Miriam sits poised at the piano as she introduces the gently rocking accompaniment that sets this bucolic music in motion, over which John's cello sings a melody suffused with longing and melancholy. Alice exchanges a faint smile with Miriam as she waits for John to hand off the melodic baton.

This scene always tickles me. Not only because we get to see A-list Hollywood actors performing classical music on screen, but also because the film takes Schubert's trio and returns the work to the environment for which he wrote it — the home. Although performances of the trio nowadays take place on barren stages in cavernous concert halls, Schubert composed this genre of music — aptly called chamber music — to be played near a crackling fire, by friends who sway to and fro as they explore every contour of the music.

At the dawn of the 19th century, domestic music-making had achieved new levels of popularity. No longer confined to the monarchy's grand palaces or the stately homes of the aristocracy, music had become a fixture of daily life in many middle-class households like that of the Schuberts. The son of a schoolteacher, little Franz was surrounded by music from an early age. A gifted singer and pianist, he also learned the viola so he could play in a string quartet with his father and brothers. And by his late teens, when Schubert began composing full-time, private salons had become the hottest spots in Vienna for enjoying intimate evenings of music.

Schubert was part of a tight-knit band of bohemians who collectively explored liberal ideals, flouted the tenets of Vienna's conservative society, and embraced an all-consuming passion for art, music, and literature. His friends revered Schubert and his music, and even regularly produced concerts, known as Schubertiades, in the homes of wealthy patrons. The focus of these evenings — aside from good food, flowing wine, and riotous laughter — was always a performance of the latest music to flow from Schubert's pen.

Many of Franz's compositions — including more than 600 songs, nine symphonies, chamber works, sacred masses, and a wealth of music for solo piano — are laced with a sweet sadness that mirrored the composer's complex emotional palette. A close friend, the poet Johann Mayrhofer, wrote that Schubert's character was a "mixture of tenderness and coarseness, sensuality and candor, sociability and melancholy." No one recognized the composer's heart-on-sleeve spirit more than Schubert himself. In a short story he wrote in 1822, the central character, who clearly serves as a stand-in for Franz, says:

"Through long, long years I sang my songs. But when I wished to sing of love it turned to heartache, and when I wanted to sing of heartache it was transformed for me into love."

These are moving words from an artist regarded as one of the finest observers of the human condition, who could express a profound understanding of seemingly every emotion swirling about the deepest chambers of the heart. Especially in his extensive song catalogue, we hear how Schubert recognized the yin and yang of life, the ways love and happiness are inextricably laced with isolation and sadness.

It's often said that when Schubert writes in a major key, the music sounds even sadder than when he writes in a minor key — as if he's showing us that any sense of relief, joy, or calm is fleeting in a world filled with so much grief and despair. And as we hear in the slow movement of the First Piano Trio, with its achingly tender conversations among violin, cello, and piano, just because those feelings are fleeting doesn't mean we can't savor every moment of their fragile beauty.

Written in a state of deepening depression during the final year of Schubert's life — a period of rapidly declining health that stemmed from his contracting syphilis five years earlier — the First Piano Trio speaks to the pleasure and fulfillment he received from his close musical collaborations. Clocking in at 45 minutes and following the four-movement structure of 19th-century symphonies, Schubert's trio could have easily been written for a grand orchestra. Instead, he composed a symphony in miniature — one he could perform with friends at their frequent get-togethers, even if he couldn't get the work programmed in a public concert series.

Creating that level of intimacy was a natural fit for a composer of songs. In fact, the trio's slow movement is in many ways a sublime song without words — one that immediately evokes feelings of Gemütlichkeit, the German term for an immediate and all-consuming sense of comfort.

The cello sets the scene with an expansive, lullaby-like melody. Seemingly tentative at first, the line builds upon a series of sighs that soar higher in the instrument's resplendent tenor until it's handed over to the violin, whose silvery tone adds a brighter tint of sweetness. Even in the movement's central section — where the piano takes a suspenseful turn with a new minor-key melody driven by riveting off-beat rhythms in the strings — we can't help but be moved by the delicate interlacing of voices, which playfully mimic each other without ever mocking. Together they embark on a voyage through distant harmonies, its playful twists and turns mirroring the many circuitous routes a late-night conversation among friends can take.

Then, following a moment of supremely satisfying suspension and resolution, the opening material returns, seemingly with more longing than before, as violin and cello take turns singing the lullaby theme above broken chords in the piano that resemble the plucking of a celestial harp. The emotional journey now complete, the movement ends in a state of hushed reverie — the earthbound cello settling into its deepest register, the violin reaching for the stars, as their lyrical dialogue evaporates into breathtaking silence.

That gentle interweaving of voices, the way each instrument supports the others with such care and compassion — this is music of deep human connection, composed using a language of friendship Schubert lovingly etched into every measure of his manuscript. It's a balm and a beacon of hope that's comforted and consoled listeners for nearly 200 years. The composer Robert Schumann, one of Schubert's greatest advocates in the decades following his death in 1828, remarked:

"One glance at Schubert's trio and the troubles of our human existence disappear and all the world is fresh and bright again."

I get misty-eyed every time I read that quote, a powerful reminder that art always offers opportunities to reframe the world around us — even if just for the eight minutes it takes to experience Schubert's lullaby of longing. It's an idea I've needed to hold close even more over the past weeks, as we're forced to confront unceasing waves of division, hatred, and brutality across the globe.

In those moments when my heart feels its heaviest, I sit with this music and dream of living in a world where people communicate using Schubert's language of friendship. Wouldn't that be lovely — to speak to one another in phrases that freely offer nothing but love and respect, kindness and affection?

Take a listen …

Among the many recordings of Schubert's First Piano Trio, my new favorite is one released earlier this year by pianist Lars Vogt, cellist Tanja Tetzlaff, and violinist Christian Tetzlaff (Tanja's brother). Close friends and musical partners for more than two decades, they had previously recorded Schubert's pair of piano trios back in 2006 before preparing a new recording in 2021.

But this would prove no ordinary recording process. Shortly after completing the album's first studio session in February, Lars was diagnosed with an aggressive case of throat and liver cancer. Committed to completing the project despite chronic pain and weakness, he scheduled his ongoing chemotherapy appointments to accommodate a second recording session in June.

Although Lars had been a prolific performer of Schubert's music throughout his career, his diagnosis must have added new layers of resonance to the melancholy music written by a composer who had died from a devastating disease at 31. After listening to the edited album for the first time, he texted Christian and Tanja to express his enduring gratitude for their love and friendship, and the music they shared:

"Now we've done it, recorded these trios — now I could go too. ... If not much time remains, then it's a worthy farewell. You two are absolutely fantastic. And Franz. Incomprehensible. Such expression. Such fragility, such love."

A worthy farewell, indeed, for a musician of incomparable kindness and artistry. Lars Vogt passed away on September 5, 2022, at the age of 51.

I'd love to hear about your experience listening to Schubert's melancholy ode to music and friendship. Does it conjure in you the same daydreams of peace and human connection I feel? Let me know in the comments.

And if you enjoyed your time here at Shades of Blue, how about tapping that little heart below? 👇🏼

Another beautiful article built around this wonderful music. How heart rending that this was Lars Vogt's final project. Like David Bowie he embraced his art until the final moment and, in Bowie's case, beyond it.

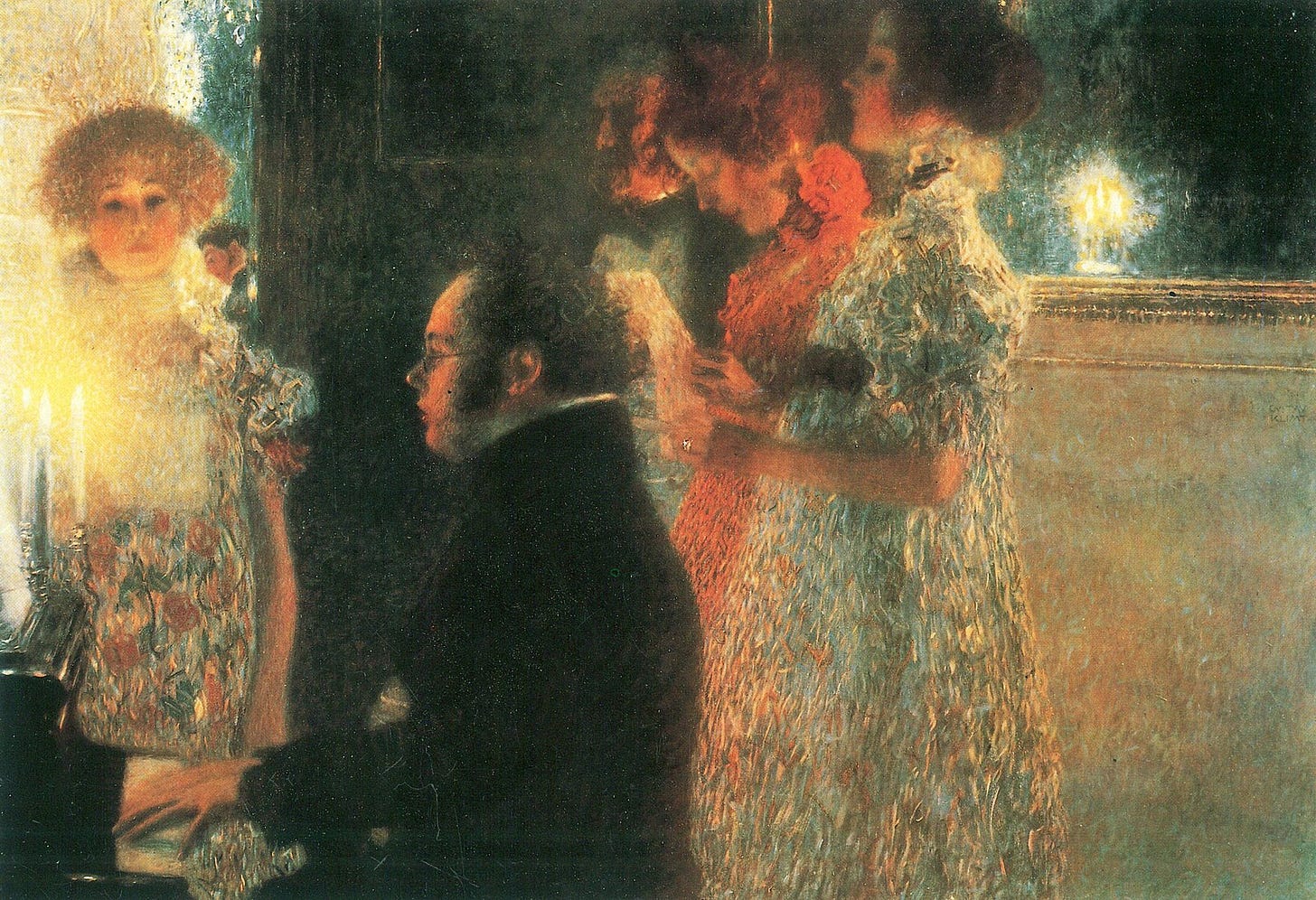

That Klimt painting is just superb. I love the beautiful illustrations you use, and as for the movies...! I just love your choice of horror viewing, and could ramble on about those three fabulous films, so I'll spare you that and just give two recommendations for anyone who hasn't seen them.

For vampire lovers, Nadja (1994) and for Oldman lovers like me, Prick Up Your Ears (1987) where he plays Joe Orton so well and resembles him so closely it's uncanny.

Thanks for another informative piece Michael. I really enjoyed it.

Gorgeous!! You’ve convinced me to build a time machine ...To be just an insignificant fly on the wall during those Schubertiades! This time I tried something new and listened to the piece before reading your essay. New depth during my second listen, especially with the added emotional layer of Schubert, Vogt, Bowie’s tragic passings. Dracula and Interview yes yes yes! But I can’t believe I’ve never seen The Hunger! To tide me over until I can, I found this beautiful edit set to Schubert’s Trio in E Flat (https://youtu.be/aHAn34xWChM) Also have to add Nadja to the list once I saw your Portishead comment and watched THE MOOD that is that trailer! 💙