Gustav Mahler / Ich bin der Welt ... (Lost to the World)

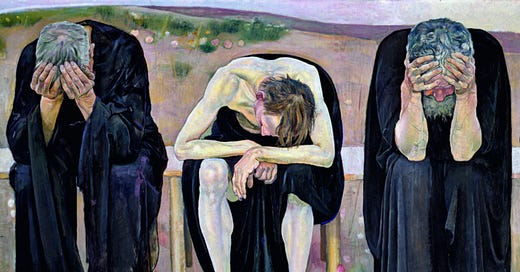

Finding a tranquil realm, far removed from the world's turmoil, where love and art help us to heal.

It's easy to think of hustle culture as a poisonous product of the 21st century, but this malady of mind and body has long plagued the overachievers among us. Just take a look at the composer-conductor Gustav Mahler's state of affairs in the winter of 1901.

Since the earliest days of his conducting career, Mahler had been focused on one goal: becoming music director of the Vienna Court Opera, the crown jewel of the musical world in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. And in 1897 that dream became a reality. The job carried a tremendous workload, however, one that was further exacerbated by Mahler taking on additional conducting responsibilities with the Vienna Philharmonic. Maintaining that chronically busy schedule — coupled with the stratospheric levels of perfectionism Mahler required of himself and the musicians he worked with — quickly took its toll.

On February 24, 1901, halfway through his fourth season as music director of the Opera, Mahler's body reached a breaking point. Following a frantic Saturday that involved conducting a Philharmonic concert in the afternoon and a performance of Mozart's Magic Flute that evening, he suffered a hemorrhage so severe he had to undergo multiple surgeries and seven weeks of recuperation to heal. Had Mahler arrived for medical treatment even 30 minutes later, his doctor said, Vienna's most famous musician would have died then and there, at the age of 41.

The events of that frosty February night forced Mahler to confront his limitations, both physical and mental. His work life was not only weakening his body, but also depriving him of time with his other great pursuit: composing. He had completed just one symphony in the four years since becoming head of the Vienna Court Opera. Realizing he was trapped in an artistic desert of his own creation, Mahler reduced his conducting workload by half.

But even with that reduced schedule, Mahler's obligations at the Opera meant he only had time to compose during the summer — just two months when he could be tucked away in the composing hut he had built in the resort town of Maiernigg, in the Austrian Alps. And that's exactly where he headed in June 1901, the beginning of a summer that would ultimately mark one of the most productive periods of his life. He not only completed half of his Fifth Symphony by the end of the summer, but also broke new ground in his work as a songwriter.

Mahler's legacy today is largely focused on his 11 symphonies — titanic, heaven-storming works that embody the hyperexpressive romanticism of fin de siècle Europe. But even before putting pen to paper to sketch his First Symphony, Mahler had already become a prolific composer of Lieder, or German art songs.

Prior to 1901, Mahler's songs were settings of his own poems or those from a popular book of German folk poetry, Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy's Magic Horn). Many of these Wunderhorn songs found their way into his first four symphonies, whether as melodies taken up by the orchestra or by adding vocal soloists to the mix. Songwriting had become so important to Mahler's symphonic writing that, when delivering the score of a new symphony to a friend in 1896, he also included a set of his songs. Mahler explained that through these Lieder, "you will best learn many things of intimate significance in my life."

During that summer at Maiernigg, Mahler was inspired to change course. After composing one final song from the Wunderhorn collection, he turned to the poetry of Friedrich Rückert, an early 19th-century writer Mahler considered a kindred spirit. In Rückert, the composer saw an embodiment of the romantic ideal — an emotional, isolated figure who found their greatest sense of peace and fulfillment in the act of artistic creation.

In contrast to Wunderhorn's stock characters and rustic folk scenes, Rückert's poems are highly personal meditations on love, beauty, and art steeped in the German notion of Weltschmerz. Literally translated as "world pain," Weltschmerz reflects the melancholy and sadness we feel when confronted by the world's imperfections. To the romantic poets, the emotional weariness triggered by the gap between our idealized visions of the world and external reality is harmful to humanity's quest for artistic and personal freedom.

Perched between the Wörthersee and the Alps in his summer hut, Mahler quickly composed seven songs based on Rückert's poetry, each in two versions — one featuring piano accompaniment, and another with orchestra. The last of these, "Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen" (I've become lost to the world), mirrors the composer's emotional state that summer — his longing for quiet solitude, his need to reconnect with the act of creation. "It is a feeling that rises to the lips but does not cross them," Mahler said of Rückert's poem. "It is my very self!"

I've become lost to the world, With which I otherwise spoiled so much time, For so long it has heard nothing from me, It would well believe I were dead! It means nothing to me If it thinks me dead, Nor can I say anything to deny it, Because really, I have passed away from the world. I have passed away from the world's turmoil And rest in a tranquil realm! I live alone in my heaven, In my love, in my song! — English translation by Michael Cirigliano II

In his setting, Mahler imbues Rückert's words with the atmosphere of a hazy daydream. Melodies rise and fall, emotions blossom and retreat, all in seamless fashion against an intimately scored backdrop. A profound serenity is embedded in each of the song's 67 bars, the music hardly rising above a whisper as the singer exalts their temporary retreat from the world.

Temporary is the key word there. For "Ich bin der Welt" is not an outright rejection of the world or a white flag of surrender to its unceasing turmoil. Instead, this marriage of poetry and music is a meditation on the power of art. Its power to inspire moments of relaxed reverie needed to escape our harsh reality — and its power to fortify our souls for re-emergence into the world. In Mahler's progression of achingly beautiful harmonies, each one intimately interlaced with hope, peace, and melancholy, we're called to manifest heavens of our own making.

Love and song abound in Rückert and Mahler's tranquil realms. What awaits you in yours?

Take a listen …

Mahler didn't specify any particular voice type for his Rückert songs, but the vocal range fits that of a mezzo-soprano or baritone. And since he composed accompaniments for both piano and orchestra at the same time, both settings similarly embody Mahler's visions for these songs.

That means when it comes to "Ich bin der Welt," there are four versions you can explore. Here I'll cover two of my favorite recordings — one featuring mezzo-soprano and orchestra, the other baritone and piano.

Listening to Janet Baker's 1968 recording with the Hallé Orchestra led by John Barbirolli never fails to transport me to a very, very happy place. The music flows gracefully without ever rushing, and Baker's voice soars effortlessly aloft a bed of gentle strings, English horn, and harp. The way she navigates the wide melodic leap up to the first syllable of stille Gebiet (tranquil realm) at 4:22 is ecstasy for the ears.

On the other side of the coin, we have baritone Christian Gerhaher's hypnotic take on the song with his longtime collaborator, pianist Gerold Huber. Having performed together for two decades at the time of this recording, Gerhaher and Huber live and breathe the score as one — the gentle push and pull of the music's pulse delivered with immaculate precision. Huber's performance of the song's coda, those final moments of contemplation after the baritone falls into silent reverie, consoles my heart like none other.

I'd love to hear about your time in Mahler's musical realm of love and calm. Let me know about your experience in the comments.

And if you enjoyed your time here at Shades of Blue today, how about tapping that little heart below? 👇🏼

Oh, that Janet Baker clip. Just takes you to the point of being a sobbing mess! Marvellous, as was the second clip. I like many genres of music but there is something about the classically trained voice that just makes me marvel at the sound a human being can make. Thanks Michael, another lovely and informative piece. x

The Weltschmerz is a really interesting concept, especially in this context. Love the way music mixes with poetry here. 🩵🩵