Maurice Ravel / Piano Concerto in G

Celebrating Shades of Blue's second birthday with a meditative waltz that reveals depths of emotion below its radiant surface.

Hi, friends,

On Monday, Shades of Blue turns two years old!

I'm so grateful for each and every one of you who have joined me here to slow down and experience the calm, connection, and healing made possible by melancholy moments of classical music. Thanks to everyone who's shared my work here with friends, family, and colleagues, this newsletter is now read by nearly 1,700 people in 80 countries.

In honor of this milestone, I'm diving into a work by one of my favorite composers, Maurice Ravel, whose music offers a portal to fantastical worlds of innocence, nostalgia, and beauty.

I hope you enjoy. And thank you, always, for being here.

— Michael

Since first encountering the music of Gustav Mahler as a teenager, I've considered the composer a guiding light. The titanic symphonies, in which Mahler sought to "embrace everything," from the flowers of the meadows to the divine love that unites the universe, thrill me with every listen. And the intimate songs that flowed from his heart to the page never fail to comfort and console.

As I struggled to find my place in the world, Mahler's life and music mirrored my turbulent emotions. For within the small handful of works he composed, we can hear an autobiography unfolding in real time as Mahler confronts love, loneliness, fatherhood, infidelity, death, and crises of faith both religious and artistic. Even the way he was treated like an outcast by a judgmental society — "I am three times without a country," he once wrote, "a Bohemian in Austria, an Austrian among Germans, and a Jew throughout the world" — resonated with me as a gay man coming of age against a backdrop of AIDS, the Defense of Marriage Act, and relentless homophobia.

But now, after 30 years with Mahler, I'm spending less time enveloping myself in his symphonies, those all-consuming explorations of the gnarled roots of life. Perhaps it's because I've finally gained a quiet confidence in my identity, or maybe because the world is already exhibiting its complex breakdown in the slow drip of my news feed. But over the last five years, I've been drawn into the orbit of another composer who viewed the world from a different angle: Maurice Ravel.

Whereas Mahler excavated body and soul in his search for universal truths, Ravel resided in the realm of the imagination, his music offering us a portal to fantastical worlds of innocence, nostalgia, and beauty. His friend Alexis Roland-Manuel wrote that Ravel possessed:

"the soul of a child who never left the kingdom of Fairyland ... who seems to believe that everything can be imagined and carried out on the material plane"

Ravel rebelled against the ideals of 19th-century Romanticism, in which composers imbued their music with drama, struggle, and expressions of profundity. Instead, he captivated listeners with the refined melodies and delicate textures he employed to evoke the fairy tale scenes of his Mother Goose Suite and the wanderlust of the Shéhérazade songs. Even his infamous Boléro — most people's introduction to Ravel through pop culture — is more consumed with color than content, its insistent melody unleashing rainbows of tints and hues with each change in instrumentation, like light through a prism.

Some of Ravel's contemporaries criticized both his work and appearance as insincere, claiming that his music never dove below its immaculately crafted surfaces, his refined dandyism merely a shield against any invasion of his private life. When asked about the popular opinion that his music was "artificial" rather than "natural," the composer responded:

"Do these people never consider that I might be artificial by nature?"

Ravel may have claimed to prioritize dazzling color over personal sentiment, but listen closely and you'll find, hidden in the contours of a sensuous melody or a particular color he extracts from the orchestra, pieces of the puzzle that make up his life and passions, a trail of musical breadcrumbs leading us into the heart that beats under the dapper dandy's meticulously tailored suit. Whenever I seek to enter those hallowed chambers, I turn to the Piano Concerto in G — a marriage of music and memory in which Ravel comes closest to delivering a self-portrait in sound.

Even as a child, Ravel proved a musical sponge. From a foundation of French Baroque dances and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's elegant piano sonatas, young Maurice began to explore musical traditions outside of Europe — including the music of Russian composers and the mystical sounds of the Javanese gamelan he encountered as a teenager attending the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris.

But to swim in the pool of sound that inspired much of his Piano Concerto in G, however, he had to travel nearly 6,000 miles, to the bustling streets of New York City.

In late December 1927, Maurice set sail for a four-month, 17-city tour of North America. Zig-zagging across the continent, he was captivated by the Midwest's vast prairies, horrified by the hectic pace of city life in the U.S., and — most memorably — bewitched by the jazz he heard.

The composer celebrated his 53rd birthday in New York City, where he attended a party thrown in his honor by the mezzo-soprano Éva Gauthier. Among the throng of celebrants eager to shake the Frenchman's hand was a 29-year-old George Gershwin, whose Rhapsody in Blue for solo piano and jazz band had left Maurice "dumbfounded." The pair hit it off, and George served as his new friend's guide to Harlem's hottest jazz clubs, from the Savoy Ballroom to Connie's Inn and the Cotton Club, where Maurice heard the swinging sounds of Duke Ellington's orchestra for the first time.

Maurice regarded George as "a musician gifted with the most brilliant, the most seductive, perhaps the most profound of qualities" — which is why, when the young American asked him for composition lessons, he replied:

"I think you're making a mistake. It is better to write good Gershwin than bad Ravel, which is what would happen if you worked with me. ... It's I who should ask you for lessons, to find out how to make so much money writing music!"

Maurice may never have soaked up George's business savvy, but he did return home to Paris inspired to compose a new work for piano and orchestra. And when the Piano Concerto in G premiered in 1932, the driving rhythms and blues-infused melodies he had heard in New York shared center stage with a musical tradition that proved formative to him: the Basque folk dances Maurice had heard during family holidays in Ciboure, his mother's hometown.

From the opening whip-crack, jaunty Basque-inspired tunes dance across the orchestra while waterfalls of notes cascade across the keyboard. Punchy drums, shrieking clarinets, and slippery slides in the brass add to the jazzy snap that dominates the movement. And in moments of hazy reverie, the piano transports us from the sounds of wild celebration to rolled chords that evoke the strumming of a Spanish guitar under a moonlit sky — a glimpse through the veil of time and space, connecting us to Maurice's cherished childhood memories.

At the emotional center of the concerto, the second movement delves beneath the music's radiant, jewel-encrusted surface to reveal new depths of beauty. The piano alone introduces a waltz both meditative and melancholy, its melody like that of an antique music box, slowly and lovingly lulling us into a state of calm. After the piano's aria, solo woodwinds add their voices to the serenade — shimmering flute, sighing oboe, and haunting clarinet engaging in tender dialogue with the soloist.

Shadows encroach upon the scene as the music builds to its ecstatic climax, a moment of spine-tingling shivers from which the opening waltz re-emerges, this time sung in the burnished, nostalgic tones of the English horn. And in its enchanting final moments, the piano's sparkling filigree arrives at a long-held trill as the music gently evaporates in the air around us, like the lingering scent of a fine Parisian perfume.

Ravel's melancholy waltz stands worlds apart from the surge of energy that characterizes the rest of the concerto. And there's good reason for that — while the work's outer movements frolic under the influence of the American jazz so fresh in his mind, this waltz reaches across the years to channel one of the composer's most profound inspirations: his idol, Mozart, whose music is synonymous with the grace and elegance of the Classical period.

In fact, Ravel used the slow movement of the Austrian composer's Clarinet Quintet as a model for the Piano Concerto in G's waltz — yet another musical fingerprint he leaves behind in the work. Like Mozart, Ravel speaks to us today on two levels: the pearly surface that enchants and transfixes, and the depths of human emotion that lie beneath, ready to comfort and sustain us.

When entering the sublime realm of Ravel's waltz, with its insistent pulse echoing the heartbeat of humanity, I never want to leave. But my longing to linger in the perpetual bliss it provides is in no way a denial of our complex, messy reality. Rather, it's because this music nourishes my undying and radical sense of hope — that humankind can one day compose an enduring harmony from its disparate parts in the way that Ravel unifies memory and imagination, the natural and the artificial, artistic inspirations both old and new.

Until that time arrives, I will turn to Mahler's symphonies when compelled to howl a primal scream into the dark midnight. And when all the catharsis I need is a single tear falling down my cheek during a moment of mesmerizing, crystalline beauty, I'll always have Ravel.

Take a listen …

Krystian Zimerman, piano The Cleveland Orchestra Pierre Boulez, conductor

I'd love to hear about your experience with Ravel's melancholy waltz. Let me know — either by replying to this email or sharing a comment below.

(And if you enjoyed your time here today, how about tapping that little heart below? 👇🏼)

Thank you for reading Shades of Blue

This newsletter is free, but paid subscribers directly support the 20+ hours of research, writing, editing, and production that go into every essay. If you look forward to reading Shades of Blue when it arrives in your inbox, please consider becoming a paid subscriber …

Or if you'd like to buy me a coffee as a token of thanks for this newsletter, you can make a donation to help keep Shades of Blue running …

What a gorgeous piece. MR is also one of my favourites, but I had never heard this. Just listening again for a second time! How fascinating that he met Gershwin.

I love this composer. Coincidentally I'm just putting the finishing touches to a short article on one of the movements from "Miroirs". He was a genius IMHO.

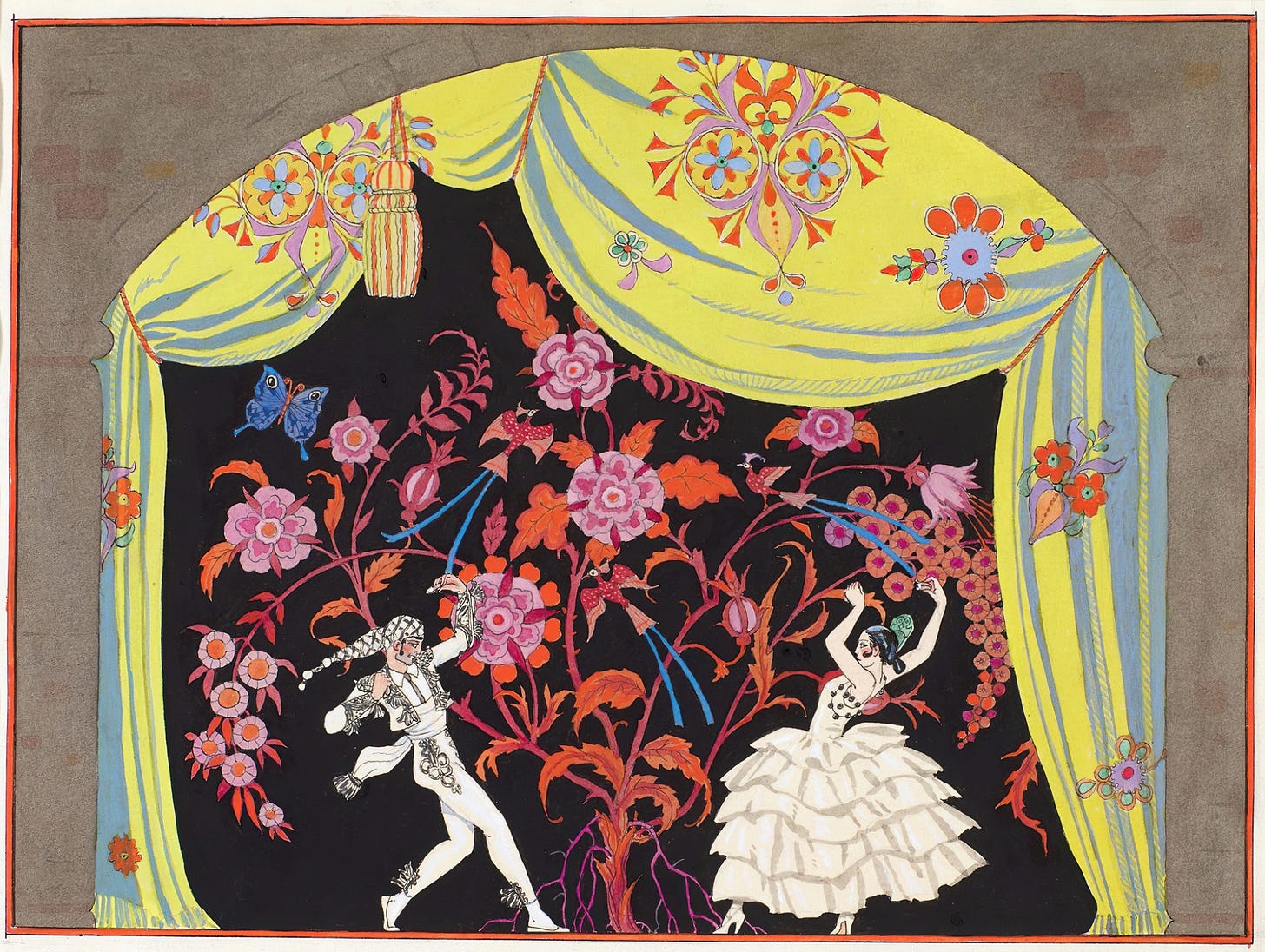

Thanks Michael. I really enjoyed the words, the music and the artwork as usual. 💙

Michael, thank you so much for your response to my note. It is very kind of you. And I continue and will continue to enjoy your marvellous writing on Substack. Warmest wishes Tim.