Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky / Symphony No. 1, "Winter Daydreams"

How did a mysterious "land of gloom and mists" help a young composer overcome a creative crisis?

The people who program orchestral concerts are often unkind to a composer's first symphony.

They know audiences will flock to a performance of Ludwig van Beethoven's Ninth Symphony to experience the oracular spectacular of its "Ode to Joy." But how many of those concertgoers have been exposed to the whimsy and charm of his First Symphony? Same for Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Of the 41 symphonies he wrote, how many orchestras turn back time to perform his first stab at the symphony? (Which, for the work of an eight-year-old, is delightful.)

I get the economics of concert programming — performing works people know and love is an easy way to sell tickets. And more often than not, these works are often the composer's most mature, written after decades of practicing their craft and learning from failures and triumphs alike. But wouldn't it be fascinating to hear how a composer began their journey with the symphony?

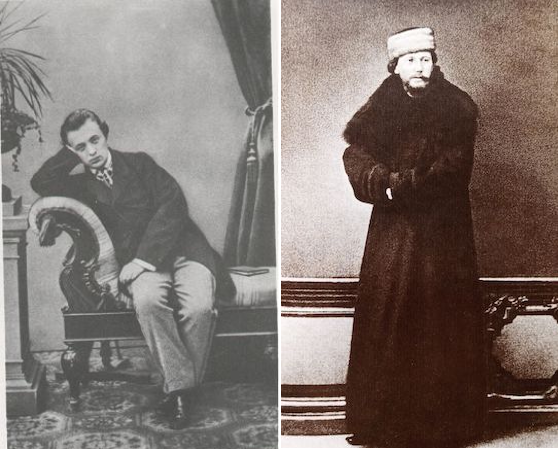

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, the crown prince of melancholy music, falls prey to this strange brand of musical favoritism. Every year, orchestral programs across the globe feature his Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Symphonies. It doesn't even surprise me when I see a major orchestra program two of them in a single season.

But his First Symphony? His first statement in a form he saw as the means to "express that for which there are no words, but which forces itself out of the soul, impatiently waiting to be uttered"? It's a rarity on the concert stage. (And in the recording studio: The classical music streaming service Idagio has 202 recordings of the Sixth Symphony and only 49 recordings of the First.)

I have a special place in my heart for Tchaikovsky's "Winter Daydreams" symphony for two reasons. First, it was the first of the composer's symphonies I got to perform, back in 1996 with the Connecticut Youth Symphony. Second, it's a profoundly moving work that has touched me deeply with every listen over the past 27 years.

The music transfixed me from the first rehearsal with CYS, as Tchaikovsky's delicate melodies, propulsive rhythms, and cinematic sense of drama took me thousands of miles away from the windowless rehearsal room I sat in at the Hartt School of Music. The first movement's late-night troika plowing through barren, snow-whipped roads. The third movement's contrasts between a shadowy, sensually sinister dance and an opulent waltz. And the minor-key folk songs woven throughout the finale, its desolate opening melody first intoned by a pair of bassoons in unison prayer before evolving into a lament for full orchestra.

Then there's the symphony's slow movement, which carries its own evocative title, "Land of Gloom, Land of Mists." Tchaikovsky establishes its dreamlike mood of longing and reverie from the opening bars, a quiet chorale for the strings led by a series of sorrowful sighs in the violins. The increasing intensity of the melody is contained only by the orchestra's persistent hush — hardly rising above a whisper, sometimes nearly evaporating into nothingness.

But that's just the introduction, and soon new voices enter to develop the main theme of the movement, one of my favorites in all of music.

Against a gently rocking motion in the violins floats a hymn of heartbreaking loneliness in the solo oboe, a gentle troubadour sharing their song of love and woe across a twilit field. A lone flute dances filigreed arabesques above — perhaps a first study for The Nutcracker's Waltz of the Snowflakes? — while the bassoon's tenuous tenor slowly descends in counterpoint to the rise and fall of the oboe's reflective melody.

That melody, first delivered with such longing in the oboe, returns twice more: passionately in the cello section's radiant upper register, and furiously in a pair of French horns — whom Tchaikovsky instructs to play "well marked and with great expression" — heightening the intensity until they bellow their final phrase over a massive body of trembling strings. But just as this emotional blizzard reaches its searing climax, the music breaks under the weight of its own power, returning to the strings' muted introduction before dying away in a place of profound calm.

Although the symphony and its first two movements have descriptive titles, Tchaikovsky's First Symphony isn't programmatic. He didn't design it to tell a story, but to elicit a specific mood for entering the work's wintry realms. Still, for more than a quarter of a century since those Connecticut Youth Symphony rehearsals, I've often wondered if that land of gloom and mists was a real location or simply the work of Pyotr Ilyich's vivid imagination.

As it turns out, it's indeed a very real place, as I learned earlier this year from a BBC Radio 3 documentary. This mystical land is Valaam: the largest island in an archipelago on Lake Ladoga, about 150 miles from St. Petersburg by boat. Cloaked in pine forest and protected by rocky beaches, Valaam is most famous for its monastery — founded in the 14th century as a northern outpost of the Eastern Orthodox Church against paganism.

For months leading up to the summer of 1866, a close friend of Tchaikovsky's, the poet Aleksey Apukhtin, had tried and failed to get the composer to accompany him on a retreat to Valaam. The 26-year-old Tchaikovsky, too caught up in composing his first symphony, repeatedly said no. And the composing was not going well.

Because of his full-time duties teaching harmony at the Moscow Conservatory, Tchaikovsky could only compose at night. And those weeks of sleepless nights spent chain-smoking and hunched over manuscript paper were catching up with him fast. Not only was he paralyzed by doubt about the quality of his work — his former composition teacher had eviscerated early drafts Tchaikovsky shared — but insomnia was triggering hallucinations and numbness in the composer's hands and feet. In July, he suffered his first nervous breakdown.

His younger brother Modest confessed in a letter:

"No other work cost him such effort and suffering … Despite painstaking and arduous work, [the First Symphony's] composition was fraught with difficulty … and Pyotr Ilyich's nerves became more and more frayed."

Knowing Tchaikovsky's health and need for recovery, Apukhtin secretly purchased two tickets for the pair to travel to Valaam. The poet slyly invited the composer to join him on board for a cup of tea before setting sail. He boasted of the blackcurrant jam served in the ship's restaurant made by the monks living on Valaam, which Tchaikovsky's sweet tooth couldn't resist. The pair feasted on their jam and sipped their tea, but it wasn't until the boat began pulling away from the port that Tchaikovsky realized Apukhtin's plan.

He was now on his way to Valaam.

As the boat approached its destination the next morning, Tchaikovsky became enamored with the island as he viewed Valaam in all its fairy-tale wonder. The remote island's natural landscape, its shadowy forests, the scurrying of its monks clad all in black — not to mention their frequent chanting, which later inspired Tchaikovsky's Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom — left the composer in awe and gave his creative energy a much-needed lift. After his time on Valaam, Tchaikovsky returned to Moscow and finished drafting the First Symphony by the end of the year. (And although there was more turmoil to endure on the way to the symphony's premiere in 1868, Tchaikovsky did learn an important lesson that summer: He never again composed after sundown.)

Despite the emotional and physical crises it inflicted, Tchaikovsky often spoke of the First Symphony as one of his favorite compositions. After a performance of the work in 1883, he said:

"I have great affection for this symphony and deeply regret that it has to lead such a tragic life."

Would Tchaikovsky have finished his symphony had it not been for the creative jolt of his trip to Valaam? I think he would have found a way. But would we have the aching beauty, the intense longing steeped in the second movement's haunting melodies, had he not traveled to Valaam? Certainly not. And for that, I'll always be grateful for this distant land of gloom and mists — and for Pyotr Ilyich's love of a good blackcurrant jam on toast.

Take a listen …

I'd love to hear about your experience trekking through Tchaikovsky's winter daydreams. Does the second movement transport you to a place of magical mystery, or perhaps an inspiring land from your travels? Let me know in the comments.

If you enjoyed this musical journey to Valaam, how about tapping that little heart below? 👇🏼

Goosebumps from the 2nd movement’s trembling quiver minute 8 onward!! Even in his first symphony here, Tchaikovsky nails the hushed twinkle swelling into heart pounding drama in mere moments (like my personal favorite from Nutcracker “Pas de deux”). The world just feels so much smaller knowing he struggled through this, and yet had a compassionate companion there to lure, um, ground him with simple creature comforts. An ordinary soul destined to give us extraordinary gifts.

And speaking of gifts, thank you for another outstanding journey! I’m officially hooked to this weekend ritual!!

This is really good. I checked out a chunk of the symphony, and it’s achingly beautiful. I need to hear more of it, and I’m eager to read more of your pieces here.