Revisiting a fabled "land of mists" that helped one young composer overcome a creative crisis

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky / Symphony No. 1, "Winter Daydreams"

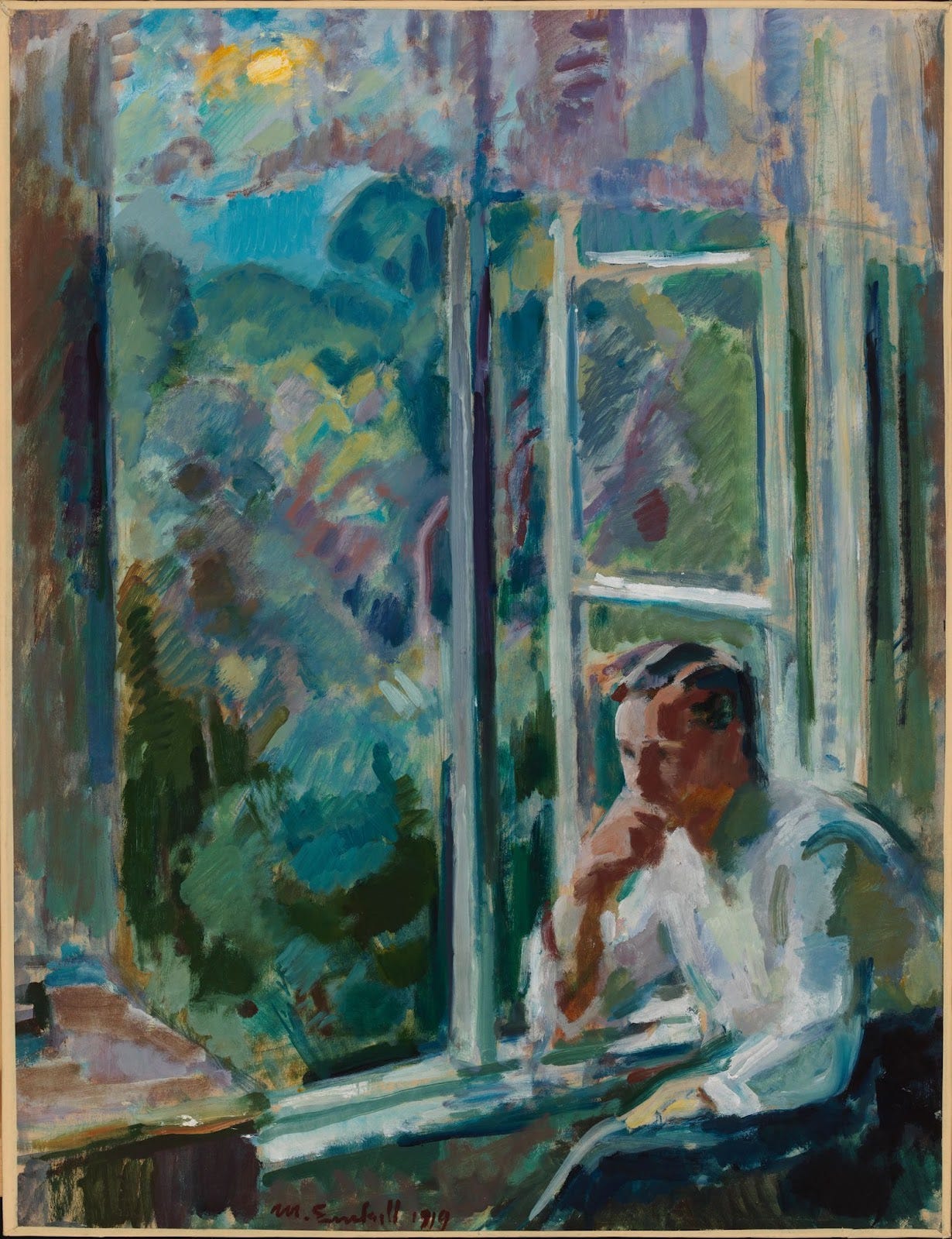

As winter's deep chill frosts the single-pane windows of my home in Minnesota, I'm finding warmth and comfort in Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's "Winter Daydreams" Symphony, a work I shared in the early days of Shades of Blue.

So join me on a musical journey through Lake Ladoga to the mysterious isle of Valaam — a land of pine-scented forests and rocky beaches that inspired a young Tchaikovsky to complete his First Symphony. Enjoy!

— Michael

The people who program orchestral concerts are often unkind to a composer's first symphony.

They know audiences will flock to a performance of Ludwig van Beethoven's Ninth Symphony to experience the oracular spectacular of its "Ode to Joy." But how many of those concertgoers have been exposed to the whimsy and charm of his First Symphony? Same for Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Of the 41 symphonies he wrote, how many orchestras turn back time to perform his first stab at the symphony? (Which, for the work of an eight-year-old, is delightful.)

I get the economics of concert programming — performing works people know and love is a much easier way to sell tickets. And more often than not, those beloved works are among the composer's most mature, written after decades of honing their craft and learning from failures and triumphs alike. But wouldn't it be fascinating to hear how composers began their journeys with the symphonic form?

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, the crown prince of melancholy music, falls prey to this brand of musical favoritism. Every year, orchestral programs across the globe feature his final three symphonies — the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth. It doesn't even surprise me when I see a major orchestra perform two of them in a single season.

But his First Symphony? Tchaikovsky's initial statement in a form he saw as the means to "express that for which there are no words, but which forces itself out of the soul, impatiently waiting to be uttered"? It's a rarity on the concert stage and in the recording studio. (Case in point: The classical music streaming service Idagio lists 219 recordings of the Sixth Symphony and only 55 recordings of the First.)

I have a special place in my heart for this symphony — which bears the evocative subtitle "Winter Daydreams" — for two reasons. First, it was the first of the composer's symphonies I ever performed, back in 1996 with the Connecticut Youth Symphony. Second, it's a work that has touched me deeply with every listen over the past three decades.

The music transfixed me from the first rehearsal with CYS, as Tchaikovsky's delicate melodies, propulsive rhythms, and cinematic sense of adventure took me thousands of miles away from the windowless room in which we rehearsed at the Hartt School of Music. The first movement's late-night troika plows through barren, snow-whipped roads, while the third movement offers a sensually sinister dance that leads directly into the minor-key folk songs of the finale, its desolate opening melody intoned by a pair of bassoons in unison prayer.

Then there's the slow second movement, which carries its own evocative title, "Land of Gloom, Land of Mists." Tchaikovsky establishes its dreamlike mood of longing and reverie from the first bars, a quiet chorale for strings led by a series of sorrowful sighs in the violins. The increasing intensity of the melody is contained only by the orchestra's persistent hush — hardly rising above a whisper, sometimes nearly evaporating into nothingness.

But that's just the introduction, and soon new voices enter to develop the main theme of the movement, one of my favorites in all of music.

Against a gently rocking motion in the violins floats a hymn of heartbreaking loneliness in the solo oboe, sung like a troubadour expressing his gentle longing across twilit fields. A lone flute dances filigreed arabesques above (perhaps a first study for The Nutcracker's Waltz of the Snowflakes?) as the bassoon's warm tenor slowly descends in counterpoint to the rise and fall of the oboe's reflective melody.

That melody, first delivered with such tenderness in the oboe, returns twice more: passionately in the cello section's radiant upper register, and then furiously in a pair of French horns, who bellow the theme over a massive body of trembling strings. But just as this emotional blizzard reaches an ardent climax, the music breaks under the weight of its own power, returning to the strings' muted introduction before dying away in a place of profound calm.

Although the symphony and its first two movements have descriptive titles, the "Winter Daydreams" Symphony isn't programmatic. Tchaikovsky didn't design it to tell a story, but rather to elicit a specific mood for entering the work's wintry realms. Still, for nearly three decades since those Connecticut Youth Symphony rehearsals, I've often wondered if that land of gloom and mists was a real location or simply the work of Pyotr Ilyich's vivid imagination.

As it turns out, it's indeed a very real place, as I learned from a 2022 BBC Radio 3 documentary. This mystical land is Valaam — the largest island in an archipelago located on Lake Ladoga, about 150 miles from St. Petersburg. Cloaked in pine forests and protected by rocky beaches, Valaam is best known for its sprawling monastery, founded in the 14th century as a northern outpost of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

For months leading up to the summer of 1866, a close friend of Pyotr Ilyich's, the poet Aleksey Apukhtin, had tried and failed to get the composer to accompany him on a retreat to Valaam. The 26-year-old Tchaikovsky, too caught up composing his first symphony, repeatedly said no.

Work was not going well for Pyotr Ilyich. Because of his full-time teaching duties at the Moscow Conservatory, he could only compose at night. And those weeks of sleepless nights spent chain-smoking and hunched over manuscript paper were catching up with him fast. Not only was Tchaikovsky paralyzed by doubt about the quality of his work — his former composition teacher had eviscerated early drafts Pyotr Ilyich shared — but insomnia was also triggering hallucinations and numbness in the composer's hands and feet. In July, he suffered his first nervous breakdown.

His younger brother Modest confessed in a letter:

"No other work cost him such effort and suffering … Despite painstaking and arduous work, [the First Symphony's] composition was fraught with difficulty … and Pyotr Ilyich's nerves became more and more frayed."

Knowing of Pyotr Ilyich's poor health and his desperate need for rest and novelty, Aleksey secretly purchased two tickets for the pair to travel to Valaam. The poet convinced the composer to see him off on his journey, and when the pair arrived at the port, Aleksey slyly invited Pyotr Ilyich to join him on board for a cup of tea before setting sail. He boasted of the blackcurrant jam served in the ship's restaurant made by the monks of Valaam, which Tchaikovsky's sweet tooth couldn't resist.

But as the pair happily feasted on jam on toast while sipping tea and enjoying deep conversation, the boat began pulling away from the port. It was then that Pyotr Ilyich realized Aleksey's plan.

He was now on his way to Valaam.

As the boat approached its destination the next morning, Pyotr Ilyich was awe-struck viewing Valaam in all its fairy-tale wonder. The remote island's natural landscape, its shadowy forests, and the scurrying of its monks clad all in black — not to mention their frequent chanting, which later inspired Tchaikovsky's Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom — left the composer astonished and gave his creative energy a much-needed lift.

After his time on Valaam, Pyotr Ilyich returned to Moscow and finished drafting the First Symphony later that year. (And although there was more turmoil to endure on the way to the symphony's premiere in 1868, Tchaikovsky learned an important lesson that summer: He never again composed after sundown.)

Despite the emotional and physical crises it inflicted, the First Symphony became one of Pyotr Ilyich's favorite compositions. After one performance in 1883, he said:

"I have great affection for this symphony and deeply regret that it has to lead such a tragic life."

Would Tchaikovsky have finished his symphony had it not been for the creative jolt of his experience on Valaam? I'm confident he would have found a way. But would we have the aching beauty, the intense longing steeped in the second movement's haunting melodies, had he not journeyed to the remote island? Certainly not. And for that, I'll always be grateful for this fabled land of gloom and mists — and for Pyotr Ilyich's deep love for blackcurrant jam on toast.

Take a listen …

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Claudio Abbado, conductor

I'd love to hear about your experience trekking through Tchaikovsky's winter daydreams. Does the second movement transport you to a place of magical mystery, or perhaps an inspiring land from your own travels? Let me know — either by replying to this email or leaving a comment here.

(And if you enjoyed this musical journey to Valaam, how about tapping that little heart below? 👇🏼)

Thank you for reading Shades of Blue!

This newsletter is free, but paid subscribers help support the 20+ hours of research, writing, editing, and production that goes into every essay. If you look forward to reading Shades of Blue when it arrives in your inbox, please consider becoming a paid subscriber …

Or if you'd like to offer a token of thanks for this newsletter, you can make a one-time or recurring donation of your choice to keep Shades of Blue running …

This whisked me back to my bread and jam kick inspired by my first read/listen! So nostalgic! What a perfect revisit for these frigid days we’ve endured this winter, thanks Michael!

Tchaikovsky warms my heart. Thank you, Michael!