Revisiting a song of longing for innocence in a world wracked by tragedy

Benjamin Britten / Before Life and After

As I spend a few weeks resting and recharging amid summer's unfolding splendor, I'm revisiting a work I shared in the early days of Shades of Blue.

The 39-year relationship between composer Benjamin Britten and tenor Peter Pears — as lovers, companions, and musical collaborators — has inspired me throughout my life, and I relish every opportunity to share their story. So let's explore one of the many songs Ben wrote for his beloved Peter: a setting of Thomas Hardy's melancholy poem "Before Life and After."

— Michael

Discovering the work of Benjamin Britten didn't just open up a whole new world of brooding, beautiful music for me to explore. The English composer also served as my portal to a feast of literary delights.

Through his opera The Turn of the Screw, I came to know Henry James's gothic tale of ghostly possession. The massive War Requiem — written to consecrate the new Coventry Cathedral after the medieval structure was obliterated by German bombs — brought me face-to-face with Wilfred Owen's lyrical anti-war poetry. And the abundance of songs Britten composed throughout his storied career helped me to dive deeper into the work of Auden, Michelangelo, Rimbaud, Blake, and Donne.

Britten largely kept his distance from the traditional forms classical composers adopt to prove their prowess. He didn't write any formal symphonies or piano sonatas, and only a handful of string quartets and concertos. Instead, the lion's share of his output is a symbiotic marriage of words and music. But why exactly did Britten compose so much music for the voice?

He had a staggering talent for setting texts, of course. From arranging English folk songs to composing his own song cycles, operas, and choral works both sacred and secular, there were few vocal forms Britten didn't imbue with his gift for illuminating poetic scenes through music.

But outside any discussions of artistic practice, Britten also had a very personal reason to write for the voice — one specific muse for whom he wrote many of his songs and greatest stage roles: Peter Pears, who was not only among the finest tenors of his day but also Britten's life partner for 39 years.

For much of those four decades, Ben and Peter zigzagged across the globe — from Austria to Australia, and from Southeast Asia to North America — performing recitals of Ben's music. Together they became the United Kingdom's most prominent musical ambassadors abroad and national treasures at home, a favorite of audiences ranging from schoolchildren to Queen Elizabeth II, who commissioned Ben to write an opera for her 1953 coronation.

The popularity Ben and Peter amassed lay in direct conflict with the conservative values of England during much of the 20th century. They were pacifists and conscientious objectors in a grueling era of world war. They were socialists at a time when the political framework was tainted by autocracy and violent nationalism. And they were homosexuals in a country highly intolerant of sexual minorities. For the first 30 years of their relationship — nearly half of each man's life — the love they shared could have destroyed their careers and landed them life sentences in jail. But despite the potential for persecution before England and Wales partially decriminalized homosexuality in 1967, Ben forever placed his music in service of the English people and their collective cultural history.

That outsider perspective the couple shared is one of the principal threads Ben laced into his music. In ways both coded and confrontational, the composer explored the conflicts between innocence and experience, society and its outcasts, public versus private personas — themes also found in the writing of Thomas Hardy. Although the two never met (Hardy died when Britten was 13), the composer considered Hardy a kindred spirit: someone whose artistic practice was also rooted in English culture, whose writing, so steeped in melancholy, conveys a tremendous sense of humanity and compassion for those confined to the fringes of society.

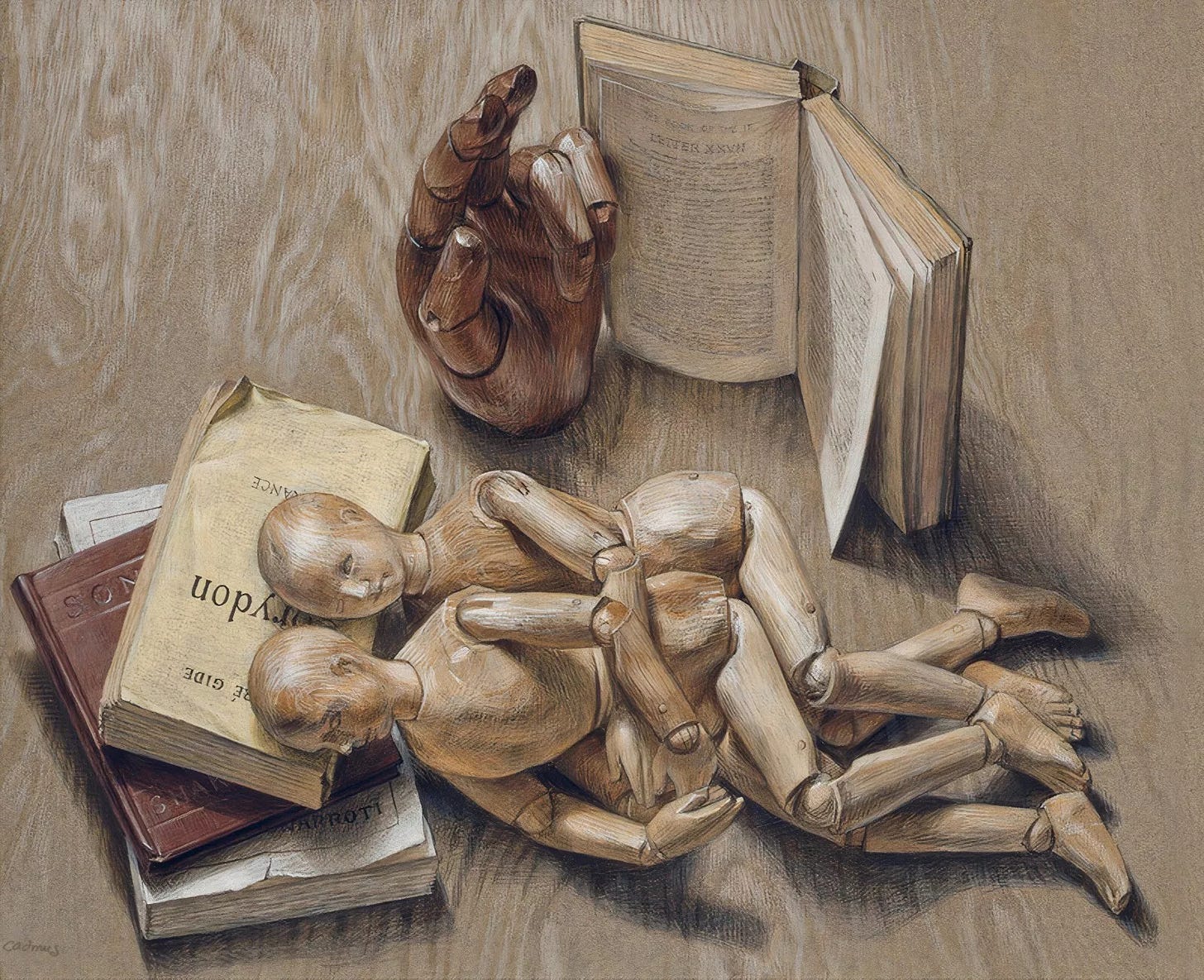

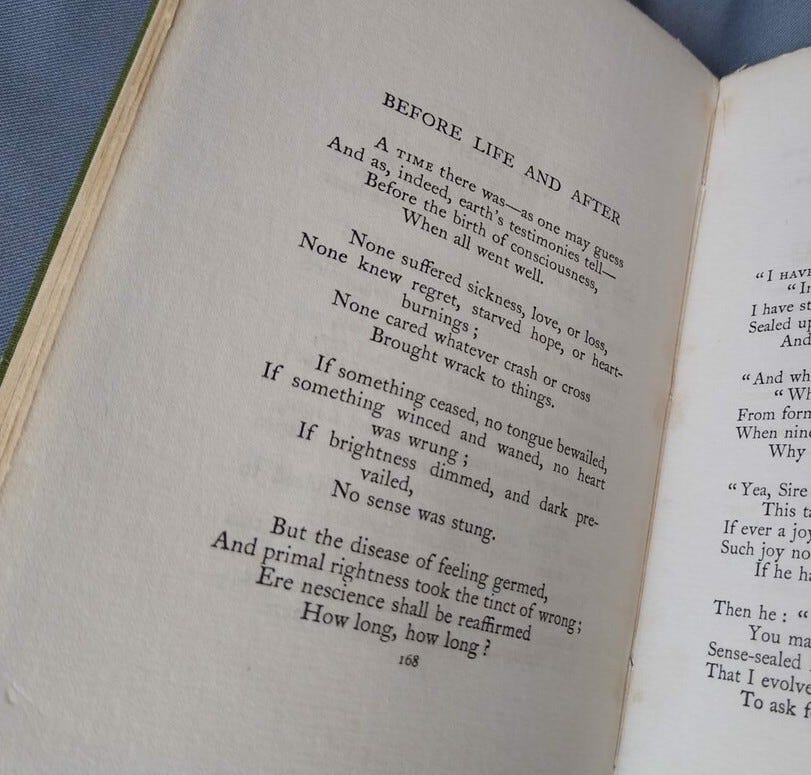

Inspired by the love for Hardy's poetry he shared with Peter, Ben composed his Winter Words song cycle in 1953, setting to music eight of Hardy's poems that capture a kaleidoscopic view of daily life in mid-19th-century England — a world of cramped train journeys, impoverished child laborers, and frostbitten gravestones. But in the collection's final song, "Before Life and After," Hardy takes us well out of any specific time or place, transporting us to the days of Edenic bliss, before the birth of human consciousness, a time "when all went well."

The first three stanzas paint a vivid portrait of humankind before the fall: a time without sickness or loss or regret, when we weren't fearful of conflict or the world's darkness. Then, in the final stanza, a longing to return to that palace of preconscious innocence takes over. The poem's final words, "How long, how long?" shatter the heart as they remind us how our desire for this primeval state can never be fulfilled.

Ben's setting of the song, lasting barely three minutes, may appear naive compared to the gravity of Hardy's text. But as is often the case with this composer's music, the world of complexity that lies beneath the song's surface is key to understanding Ben's compositional style, which, as the New Yorker's Alex Ross perfectly states, uses "simple means to express fathomless depths."

Marked "quietly moving, always soft and smooth," the music for the first three stanzas is filled with quiet reverie for those fabled days. The melody begins in the singer's highest register, filled with musical sighs and falling phrases. Underneath the voice, the piano's right hand provides a languid, unadorned counterpoint, while the left hand's insistent rhythm pulses in the depths of the piano like the soft crunching of grass underfoot. Built on the most basic building block of traditional harmony, the triad, the music drives us forward, delivering momentary reprieve only in the final line of each stanza — just enough time to catch our breath before the march of longing begins anew.

As we enter the final stanza — "But the disease of feeling germed / And primal rightness took the tinct of wrong" — the music grows to an overwhelming intensity. Instead of the sighs and gentle downward motion that have caressed our ears, the vocal line begins low and continues upward, phrase by phrase, culminating in a searing eruption of emotion. As the voice cries out with the poem's final question, "How long?" the piano's right hand mimics the pealing of bells, while the left hand's obsessive march amplifies the singer's despondent demand for a return to innocence.

Unlike Hardy, who only poses the question twice, Ben delivers it five agonizing times. Of course, neither Hardy's poem nor Ben's song answers that profound question, leaving us to continue our search for deliverance in an ever-coarsening world wracked by fear, loss, and the slow starvation of hope.

But on the other side of our human tragedy lies love. Like all of the songs Ben wrote for Peter, "Before Life and After" is a manifestation of the love the couple shared — which they, in turn, shared with people around the world through their music-making. The song would go on to hold a special place of importance for the composer late in his life.

Twenty years after writing Winter Words, Ben was in a bleak physical and emotional state. While undergoing heart surgery in 1973 to replace a faulty heart valve, he suffered a mild stroke that weakened his right arm, ending his career as a pianist and conductor. Although composing was now a physically challenging act to endure, Ben focused on what would ultimately be his last work for orchestra: the Suite on English Folk Tunes, a collection of his favorite folk music from childhood. To that nostalgia-laced work, Ben added the subtitle "A time there was ..."

To understand the placement of the first line of Hardy's poem on the suite's title page, we turn to one of the couple's many tender and heart-melting letters. Shortly after Ben finished sketching the new suite in the couple's home in England, he wrote to Peter in New York:

"My darling heart … I feel I must write a squiggle which I couldn't say on the telephone without bursting into those silly tears —

I do love you so terribly, and not only glorious you, but your singing. I've just listened to a re-broadcast of Winter Words, and honestly you are the greatest artist that ever was — those great words, so sad and wise, painted for one, that heavenly sound you make …

What have I done to deserve such an artist and man to write for? …

I love you,

I love you,

I love you — B."

Already swept up in the lifetime of memories his folk song suite had conjured, and with Peter thousands of miles away for the Metropolitan Opera premiere of his final opera, Death in Venice, Ben's reunion with that broadcast of Winter Words prompted not only a spectacular confession of love, but a means to forever encode that affection for Peter in his new work. Having come to terms with his declining health and accepting that the days he had left were far too few, he chose to express that love both nobly and unabashedly.

Take a listen …

Peter Pears, tenor Benjamin Britten, piano (Follow along with Hardy's poem.)

Thankfully for us, Ben and Peter spent a lot of time in the recording studio. So when it comes to listening to "Before Life and After," the best place to turn is the couple's own performance. Feel the warmth of Peter's honey-coated tenor, the way he floats the melody while delivering the text with perfect clarity. Savor the intimate interplay between melody and accompaniment, delivered by two musicians who felt the pulse of each other's hearts as strongly as that of their own. I dare you to listen without tearing up.

I'd love to hear about your experience with Britten's song of love and longing. Let me know — either by replying to this email or sharing a comment below.

(And if you enjoyed your time here today, how about tapping that little heart below? 👇🏼)

Thank you for reading Shades of Blue

This newsletter is free, but paid subscribers directly support the 20+ hours of research, writing, editing, and production that go into every essay. If you look forward to reading Shades of Blue when it arrives in your inbox, please consider becoming a paid subscriber …

Or if you'd like to buy me a coffee as a token of thanks for this newsletter, you can make a donation to help keep Shades of Blue running …

I've always loved Peter Pears' voice. Completely sent by that remarkable piece!

I've been to Coventry Cathedral - the closest thing to a religious building as an art gallery that I've ever experienced, with contributions by Elisabeth Frink, Graham Sutherland, John Piper and others. So interesting to read about something I couldn't see: Britten's contribution to the consecration of the new building. I didn't know that "War Requiem" was written for that.

I love that picture of the two of them with Copland.

What a power couple they were, and I mean that in the most important sense: artistically.

Thanks Michael. Loved this. 💙

What a wonderful article! I just moved. You inspired me to dig out my speakers and listen. Benjamin Britton will be the first music I play in my new home.