Why I'm devoting this newsletter to melancholy classical music.

What is life, if not a symphony of sorrowful songs?

The way classical music is marketed often leaves me furrowing my brow. Especially when I hear classical crossover, the term record label executives apply to classical music albums purposefully packaged and marketed to find success with "mainstream" audiences.

Neither the marketer nor the musician in me sees how this approach does anything but alienate the product. It presents classical music as such a fringe element of our culture that a successful recording must include a superstar name, a glossy cover image of said superstar keeping it "cool" or "sexy," and mediocre orchestral arrangements of pop hits to convince music lovers at large to take a chance on a classical artist. (Case in point: Soprano Renée Fleming's cringy deep-dive into Björk, Arcade Fire, and Tears for Fears covers.)

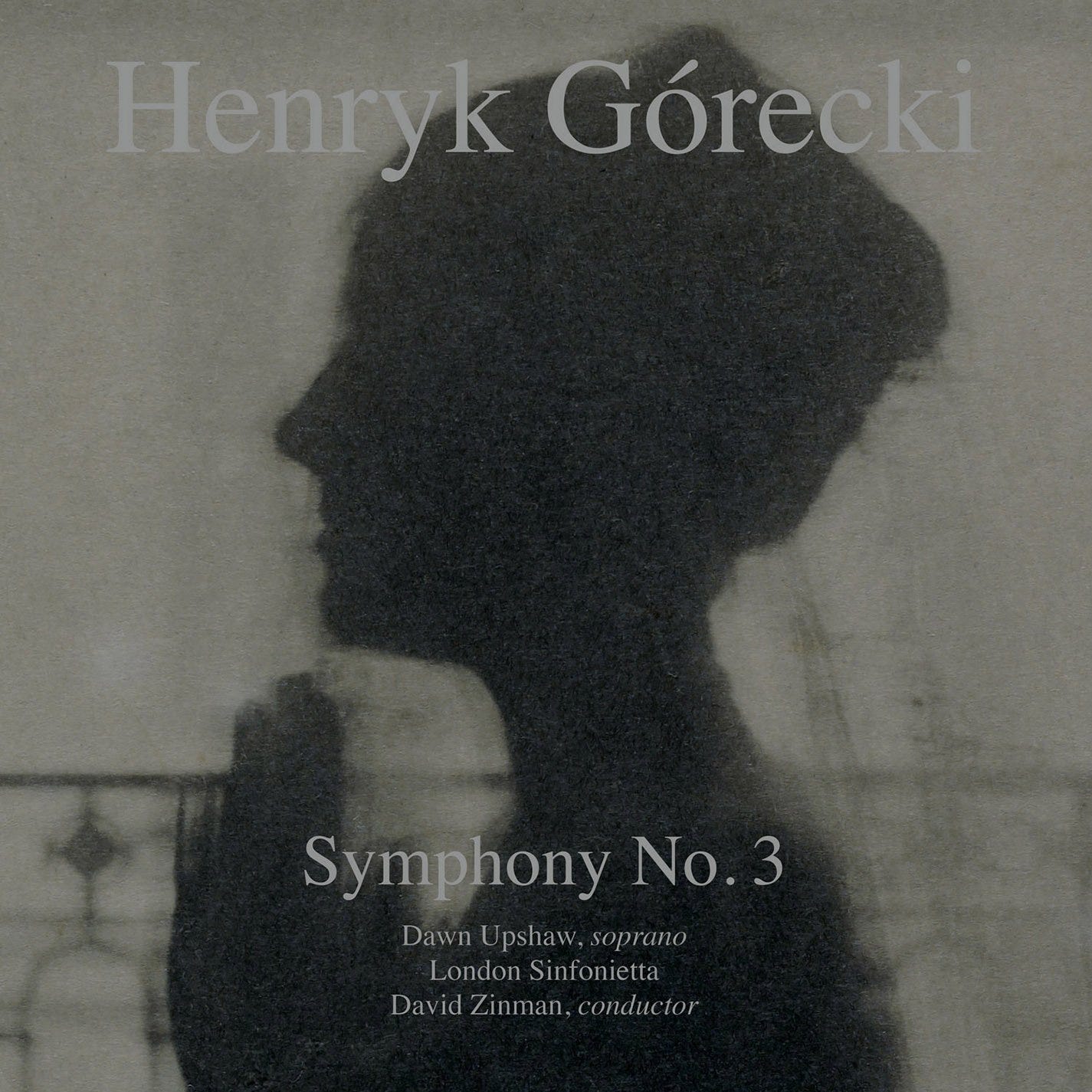

In 1992, the Nonesuch label shot a hole through every one of those assumptions about classical music marketing, when it released an album that took the world by storm without following the classical crossover playbook. The music was largely unknown, the composer an obscure figure to anyone outside of classical music circles, and the cover art was simply a gray-scale image of a shadowy figure in profile, hands pressed together in peaceful reverence.

The album featured just one piece of music: Symphony No. 3, the Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, from Polish composer Henryk Górecki (pronounced Hen-rick Gore-et-skee). Written in 1976, Górecki's symphony is a vast, hour-long work for orchestra and solo soprano in three movements, each of which sets to music a Polish text — from a 15th-century lament of the Virgin Mary to a prayer etched onto the wall of a Gestapo prison cell — that explores motherhood and grief, war and loss.

The record executives at Nonesuch thought the work, performed by the London Sinfonietta and featuring a young singer named Dawn Upshaw, would resonate with listeners. They hoped to sell 25,000 to 30,000 copies.

A year after its release, the album had sold more than 600,000 copies.

It sat at the top of the U.S. Billboard Classical chart for a staggering 38 weeks and remained in the top 40 for nearly three years. And in the U.K., the album made its way to the pop charts — read that again, the British pop charts — where it peaked at number six, sandwiched between En Vogue's Funky Divas and R.E.M.'s Automatic for the People.

To date, it's sold more than a million copies, making it the best-selling album of a piece of contemporary classical music.

Why was a largely unknown work, saturated in sorrow with texts written in Polish, such a runaway hit in the English-speaking West?

The album's success was partly due to the extensive air time the symphony's central movement received during the launch of a new British radio station for classical music, Classic FM. At 10 minutes long, it was the only movement that could be easily slotted into a disc jockey's queue (the first and third movements clock in at 25 minutes and 17 minutes, respectively). Interest in the work increased as listeners discovered the emotional impact of the music's profound simplicity — its entrancing, meditative mood, anchored by a modest, unadorned melody in the soprano that rises and falls with effortless, slow-moving grace.

Then, of course, there's the work's mysterious subtitle. Symphony of Sorrowful Songs: Four words so seemingly abstract, yet specific enough so as to leave no doubt this symphony was a portal to a very particular emotional world. (The Nonesuch execs couldn't have asked for a better headline for their marketing.) Between the evocative title and the shadowy cover art, it was clear this wasn't a recording to listen to during morning runs or Sunday brunch.

And they bought it anyway — in droves.

No one was more surprised at the success of the Nonesuch album than Górecki himself. No work of his had ever captured — and no album of his music would again capture — the public's interest like his Symphony of Sorrowful Songs. When asked about the piece's unexpected popularity, the composer said:

"Perhaps people find something they need in this piece of music. ... Somehow I hit the right note, something they were missing. Something, somewhere had been lost to them. I feel that I instinctively knew what they needed."

The search for what we're missing, what's been lost to us.

In her book Bittersweet, Susan Cain dives deep into the emotional capacity of sorrow and longing, and how we can find creativity, connection, and transcendence by embracing what she calls the bittersweet in life: sad songs that provide solace and comfort, rainy days that inspire us, ordinary moments in nature that leave us in total awe.

"The bittersweet is not just a momentary feeling or event," Cain says. "It's also a quiet force, an authentic and elevating response to the problem of being alive in a deeply flawed yet stubbornly beautiful world. ... Bittersweetness shows us how to respond to pain: by acknowledging it, and attempting to turn it into art, or healing, or innovation, or anything else that nourishes the soul."

If you've made it this far into this essay, chances are you have an idea of what Cain is referring to. Although many of us consume music using streaming services and earbuds to create the soundtracks of our lives in motion, there are a whole host of benefits to listening to bittersweet music that invites us to slow down, reflect, and feel.

There's something unique about the effect bittersweet music has on our physical and emotional worlds. The way hearing Samuel Barber's Adagio for Strings at times of mourning can help uplift us, rather than allowing us to sink deeper into our sadness. Or how the "love" theme of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky's Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture releases a kaleidoscope of butterflies through our circulatory system, despite knowing the tragedy that befalls Verona's most famous couple.

Research from a 2016 study by the European Society for the Cognitive Sciences of Music found that emotional responses to sad songs fall into three categories. Unsurprisingly, some respondents said this music induces negative feelings like grief, anger, and despair. But the majority shared how sad music produces feelings of melancholia — a gentle sadness or sense of longing — as well as a sweet sorrow that helps them tap into ideas of consolation, appreciation, and hope.

So while many people may think listening to sad music is a mode of wallowing in deep pools of grief or self-pity, more often this bittersweet music is transforming our state of mind, driving us to find calm and healing through the experience of living. Or as Cain puts it:

"Upbeat tunes make us want to dance around our kitchens and invite friends for dinner. But it's sad music that makes us want to touch the sky."

Touch the sky — and expand our horizons. That's the profound effect melancholy moments of classical music have had on me throughout my 44 rotations around the sun.

Growing up in the flat, unremarkable world of suburban Connecticut in the 1990s, classical music became my form of rebellion against the aggressive music my parents enjoyed. At any point in my childhood, you could hear Ozzy Osbourne's wail on Black Sabbath's Paranoid erupting from my father's stereo on one end of our house, while the sweet sighs of Beethoven's Violin Concerto wafted through the air outside my bedroom on the other.

More importantly, I was energized by the ways the experience of listening to these works engaged mind, body, and soul. Unlike paintings and sculptures, which need to be observed in books or from a museum-permitted distance in a gallery space, I could feel the music vibrating in every fiber of my being, transforming me at a cellular level. No matter my mood (but especially when I was feeling a blistering sense of ennui and melancholy, as was often the case for Gen Xers in the '90s), I could come to this music to confront my emotional depths, soar through my emotional highs, and find a profound sense of communion with composers who experienced challenges in their lives similar to those I faced. And I could do that whenever I wanted.

Decades later, classical music still lives up to the promise posed by the conductor Leonard Bernstein, that it "leaves us at the finish with a feeling that something is right in the world. Something that checks throughout. Something that follows its own law consistently. Something we can trust — that will never let us down."

So why start a newsletter exploring only melancholy classical music?

Firstly, I've never felt a more urgent need to transport body, mind, and soul to — in Cain's words — a beautiful, more perfect world outside our own. In a time of ideological division, the erosion of civil rights, and perpetual doom-scrolling, this music helps me foster calm, beauty, and healing in my life. And I have a feeling you're searching for the same right now.

Secondly, the drive to start this newsletter comes from the primary call-to-action Cain lays out in Bittersweet:

"Whatever pain you can't get rid of, make it your creative offering — or find someone who can make it for you. What are they expressing on your behalf — and where do they have the power to take you?"

So what is the personal pain I can't get rid of?

The fact that I no longer live my life as a performing musician. After playing the clarinet for 23 years and getting two degrees in classical performance, I realized soon after hitting 30 that the life of a freelance classical musician wasn't for me. I was too introverted to properly network and find people who could advocate for me and my career, too unforgiving to accept the imperfections in my playing, too insecure to continue competing with the ever-expanding pool of young musicians graduating from conservatories every year, hungry to win the orchestral jobs I had always dreamed of holding.

I felt a sorrow within me, that I could no longer connect directly with an audience, performing in front of them and absorbing their joy, astonishment, and inspiration in real time. But Cain's book helped me discover that I can connect with people who share in my quest to forge beauty in our lives with music — not by performing classical works on a concert stage, but by writing about them in a way that encourages exploration and connects readers with musical vehicles for finding calm. Everyone is welcome on this journey — no prior knowledge of classical music necessary.

So what can I express on our collective behalf? Where do I have the power to take you? It's time to figure out those answers, together.

In Shades of Blue, I'll be your guide to discovering this music. Every two weeks, I'll pop into your inbox to share a piece of classical music that has moved me, consoled me, and added depth of color to my life. And although the focus of this newsletter is melancholy classical music, it won't be a place to revel in sadness and grief, and we won't be focusing solely on music of tremendous sorrow. (I promise there won't be a steady stream of requiem masses.)

I won't compel you to listen to the music I share here because it's great or because the composer is important. Those are hollow, meaningless labels used too often in classical music marketing that don't showcase any of the benefits of actually sitting down and experiencing this music.

Instead, we'll explore these works to consider questions of life and death, joy and sorrow, love and loss, and witness within ourselves the transfiguration — physically, emotionally, spiritually — made possible through music that transports us to that beautiful, more perfect world.

Which brings us back to Górecki, and the second movement of his Symphony of Sorrowful Songs.

If there were a composer equipped to write a symphony of heartbreaking sorrow, it was Górecki. He was born in Poland in 1933, the same year Hitler and his party came to power. He lost his mother at the age of two. His hometown — in the Silesia region of Poland, just 20 minutes away from the concentration camps at Auschwitz — was so polluted that falling snow turned black with ash in its journey from sky to ground.

But you wouldn't necessarily guess any of that from listening to the opening bars of the symphony's second movement. The motive repeated throughout the opening bars blossoms, radiating a warmth and gentle glow that comforts as much as it transfixes. But as the mood quickly shifts and a dark hush takes over the orchestra, we realize the light is not that of a clear blue sky, but a singular sunbeam penetrating a deep darkness.

Górecki has set the scene for the solo soprano, who begins singing a short prayer written by Helena Wanda Błażusiakówna, an 18-year-old prisoner who etched the text on the wall of a Gestapo cell in Poland with a fragment of her own broken tooth:

Mama, do not cry, no

Most pure Queen of Heaven

Support me always

Hail Mary

The soprano imparts the first line — three quiet, quivering calls of Mama — in their huskiest low register, whispers of consolation as time seemingly stands still in the orchestra's static bed of string sound. But as Helena transfers the subject of her prayer from her biological mother to the Holy Mother of God, the music moves slowly upward, each phrase of the text infused with additional layers of luster. After her appeal to the Virgin Mary, the soprano returns to repeated calls of Mama, this time singing that blossoming, comforting melody the violins presented at the start of the movement.

Helena's words aren't messages of fiery anger and frustration — instead, they offer hope and consolation. And that's exactly why Górecki chose to set her prayer in his symphony. In an interview, he shared that:

"I have always been irritated by grand words, by calls for revenge. ... In [the Gestapo] prison, the whole wall was covered with inscriptions screaming out loud: 'I'm innocent,' 'Murderers,' 'Executioners,' 'You have to save me.' Adults were writing this, while here is an 18-year-old girl, almost a child.

And she is so different. She does not despair, does not cry, does not scream for revenge. She does not think about herself; whether she deserves her fate or not. Instead, she only thinks about her mother, because it is her mother who will experience true despair. This inscription was something extraordinary. And it really fascinated me."

Through Helena's words, Górecki saw opportunities to express how love could eclipse grief, how much of our lives are driven by forces outside of our control, how we can heal ourselves by attempting to alleviate the pain of others.

Love, release, healing — and one final element added by the composer. After Helena invokes the first words of the Hail Mary, which the soprano sings perched aloft one note, a sweet sense of floating far removed from the gravelly depths from which the movement began, Górecki ends his song by adding the rest of the Catholic prayer's opening line: Full of grace.

Take a listen …

I'd love to hear about your experience with Górecki's sorrowful song. Are you overcome by an overwhelming sadness, or does the movement's meditative quality take hold of you, as slices of divine shimmer cut through the dark atmosphere surrounding them?

Perhaps you feel all those things — perhaps you feel a whole lot more. Be sure to let me know below, as we embark on our shared journey through classical music's most melancholy, bittersweet moments in search of calm, connection, and healing.

If you enjoyed this journey through Górecki's Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, would you let me know by tapping on that heart below? 👇🏼

This is a beautifully written manifesto/essay, Michael. You describe your newsletter as one which will connect with people seeking to "forge beauty" in their lives by presenting writing about classical music that encourages exploration and connection with musical works as "vehicles for finding calm." What a wonderful idea for a newsletter! And quite timely too. As you state, "In a time of ideological division, the erosion of civil rights, and perpetual doom-scrolling, this music helps me foster calm, beauty, and healing in my life."

To answer the question you ask in your essay, I hear in Górecki's symphony a hint of the transcendent. I remember my first encounter with this music. It evoked for me a sense of profound melancholy but also an awareness of the human record. It was roughly about the same period in my life that I'd discovered Claude Lanzmann's monumental documentary Shoah. But I could also hear echoes of Górecki in the imagery of Czeslaw Milosz in collections like Rescue or City Without a Name.

I'm looking forward to the next edition of your newsletter.

Wow, Michael! This felt like a piece of music in and of itself, movement to movement. Such a journey!! And I had no idea what to expect from this symphony, but how you described the single beam of light in the dark is precisely what I heard (complete with dust speckles!) I was also transported to my teenage self in the 90s listening to my parents copy of Bernstein’s Mass on vinyl. I’m not sure why, but it’s the same beautifully sad melancholia. I’m so excited for more (please!)