Branching Out / Vol. 10

What to listen to next, based on our recent experiences with the melancholy music of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Philip Glass.

Welcome to the 10th edition of Branching Out — where works recently featured in Shades of Blue become your launching point for discovering more melancholy music that cultivates calm, connection, and healing. (If you're a new subscriber, head over here to explore previous installments.)

To grow our tree of classical music knowledge this month, we'll explore music inspired by our experiences listening to the wintry daydreams evoked in Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's First Symphony and Philip Glass's Fourth String Quartet, a meditative impression of an artist struck down by AIDS.

So let's dig in and branch out …

If you enjoyed discovering how an impromptu trip to a mysterious island of "gloom and mists" inspired Tchaikovsky to complete his First Symphony, you might be wondering, Michael — did Tchaikovsky's travels inform any other works? If so, take a listen to ...

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky / Adagio cantabile, from Souvenir de Florence (Memory of Florence)

In 1890, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky mailed a copy of his latest score, a four-movement work for string sextet, to his longtime benefactor, Nadezhda von Meck. "I know you love chamber music, and I am glad you will be able to hear my sextet," he said in an accompanying letter to the gravely ill Meck, "I wrote it with the greatest enthusiasm and with the least exertion."

While Tchaikovsky chose his words carefully to lift his patron's spirits, the letter included two bald-faced lies: He actually had little enthusiasm for composing the work, and the exertion required to finish the sextet spanned five grueling years.

The piece, entitled Souvenir de Florence, was Tchaikovsky's thank-you to the Saint Petersburg Chamber Music Society, which had awarded him an honorary membership in 1886. But from the get-go, the composer's crippling self-doubt — and the fact that he hadn't ever written a work for pairs of violins, violas, and cellos — made composing the sextet an arduous process. Even after shelving his sketches for three years in frustration, he encountered many roadblocks, writing to his brother Modest:

"I began [my sextet] three days ago and am writing with difficulty, not for wont of new ideas, but because of the novelty of the form. One requires six independent yet homogeneous voices. This is unimaginably difficult."

Inspiration finally struck Tchaikovsky in 1890 during a three-month stay in Florence, where he had checked into a river-view room at the Hôtel Washington to compose his latest opera, The Queen of Spades. The composer had always been enchanted by Italy, and he regularly visited Florence, Rome, and Venice to escape Moscow's harsh winters.

"I am under a clear blue sky, where the sun is shining in all its magnificence," he wrote during one of his stays. "There's no question about rain or snow, and I go out wearing nothing but a suit … a magical shift is finally happening to me."

On one of his tranquil walks along the Arno River in the winter of 1890, he sketched a duet for violin and cello that became the central theme for the second movement of his string sextet. Following a solemn, curtain-raising intro, we hear a pulse of plucked strings evoking the strumming guitars Tchaikovsky heard on his moonlit walks. And floating high above in the first violin is Tchaikovsky's Florentine melody, which he marks dolce cantabile — "sweetly sung" — in the score. Later in the movement, the violin's aria blossoms into a rapturous love duet with the first cello.

Tchaikovsky continued working on his Souvenir de Florence for another two years, revising much of the third and fourth movements even after its first performances. In the end, all the effort appeared to be worth it to Tchaikovsky, who wrote to a friend about the work:

"It's frightening to see how pleased I am with myself."

Leonidas Kavakos and Lisa Batiashvili, violin Antoine Tamestit and Blythe Teh Engstroem, viola Gautier Capuçon and Stephan Koncz, cello

If you were moved by Philip Glass's Fourth String Quartet, which honors the life and work of his close friend Brian Buczak, who died of AIDS at 32, be sure to spend some time with ...

Maurice Ravel / Menuet, from Le Tombeau de Couperin (Memorial to Couperin)

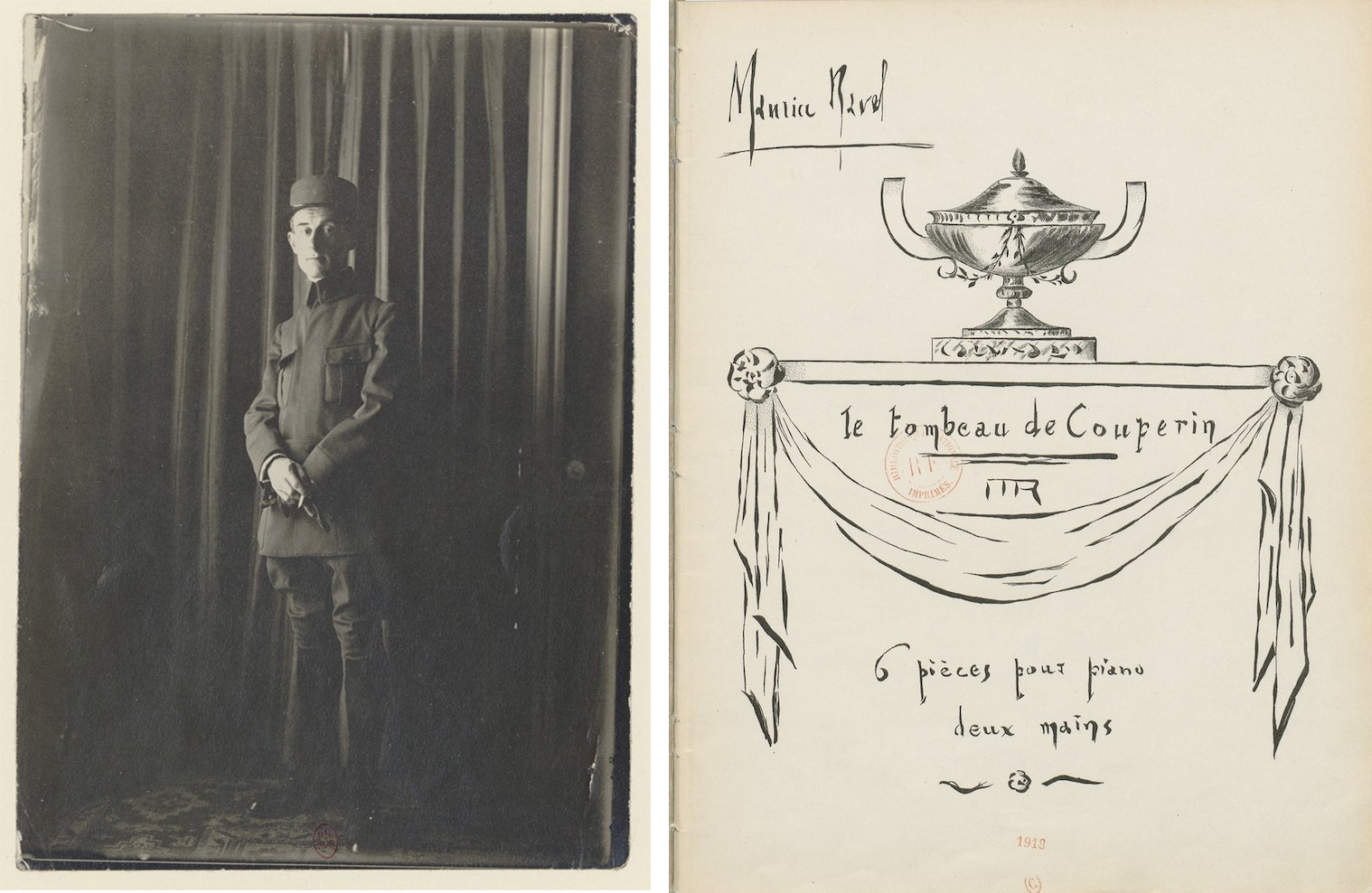

When World War I broke out in 1914, Maurice Ravel had high hopes of serving his country as a pilot in the French Air Force — a dream that was quickly dashed due to his history of fragile health and ultra-featherweight build. (Ravel stood just 5'3" and weighed 108 pounds.)

After pulling a few strings, however, he enlisted in the Army's Thirteenth Artillery Regiment in 1916, where he worked as an ambulance driver along the front lines at Verdun. There he encountered countless scenes of carnage and suffering, describing the war-torn region as:

"horribly deserted and mute ... I don't think I'll ever feel a deeper and stranger emotion than this kind of mute terror."

The composer's military service was cut short: He contracted dysentery after six months of duty, and while convalescing in Paris in January 1917, his mother passed away. Believing that his mother's "infinite tenderness" was his "only reason for living," Ravel sunk into a deep depression. Upon his final discharge later that year, a close friend, the pianist Marguerite Long, described him as "depressed, thin, and suffering from neurasthenia [what we today call PTSD]."

Ravel spent the remaining months of the war in Normandy, where he took up residence in the family home of his friend Alexis Roland-Manuel, whose stepmother, Madame Dreyfus, had been one of Ravel's most comforting pen pals while stationed in Verdun. At the Dreyfus home, he returned to a work begun shortly before the war: a series of traditional French dances entitled Le tombeau de Couperin — a musical monument to one of his favorite composers of the Baroque era, François Couperin.

Ravel had envisioned his new work for solo piano as a homage to French dance music of the 18th century, although by the time he completed the suite in 1917, it had evolved into a more profound commemoration. Ravel dedicated each of the six movements to a friend who died in the war, and he even designed the cover of the score's first edition, complete with his own pen-and-ink drawing of a funerary urn above a mourning drape.

But Ravel's tombeau doesn't mourn the loss of his friends with music of anguish and impenetrable darkness. Instead, he celebrates their lives with a work of grace, tranquility, and shimmering color.

In the Menuet — dedicated to the memory of Jean Dreyfus, the stepson of his dear Madame Dreyfus — we hear the lilting, music-box strains of a courtly dance, one infused with naïveté and quiet joy. Dark clouds momentarily enter the scene in the melancholy central section, where a minor-key melody hovers like a phantom while tolling bells sound in the depths of the piano. But in the blink of an eye, those clouds evaporate and we return to the opening strains of the sun-drenched menuet.

By choosing to memorialize his friends with music of radiant, crystalline color, Ravel reminds us that these men, who died so devastatingly young during one of the darkest times in history, should not be remembered by the inhumane circumstances of their deaths, but by the love and light they embodied during their lives. Responding to criticism about the light-hearted tone of his tombeau, Ravel simply said:

"The dead are sad enough, in their eternal silence."

After the 1919 premiere of Le tombeau de Couperin by Marguerite Long — the widow of Joseph de Marliave, to whom the suite's final movement is dedicated — Ravel orchestrated four of the six dances, including the mesmerizing menuet. Take a listen to both versions — which tugs at your heartstrings more?

Seong-Jin Cho, piano

Sinfonia of London John Wilson, conductor

I'd love to hear about your experiences listening to these works. Let me know — either by replying to this email or leaving a comment.

(And if you enjoyed your time here today, would you ever so kindly tap that little heart below? 👇🏼)

Thank you for reading Shades of Blue!

This newsletter is free, but paid subscribers help support the 20+ hours of research, writing, editing, and production that goes into every essay. If you look forward to reading Shades of Blue when it arrives in your inbox, please consider becoming a paid subscriber …

Or if you'd like to buy me a coffee as a token of thanks for this newsletter, you can make a donation to keep Shades of Blue running …

Beautiful selections as always. Le tombeau is one of my favorite pieces. I love the richer orchestral version but the piano is very personal in its own way. I didn’t know the circumstances that led Ravel to compose this, so thank you so much for your essay, Michael. It makes listening to it so much more meaningful. Have a great day!

Oh don’t make me choose!! The orchestral version is breathtaking, but something about the piano version—for being an homage to the 18th century, it sounds so modern, ahead of its time perhaps, like jazz. So you know me, I went into my rabbit hole and learned about Ravel’s love of and influence on jazz.. Miles Davis even mentioned his Dorian mode nod to Ravel on Kind of Blue. A melancholy but hopeful sound that paints a quiet celebration of his fallen brethren. Fascinating!!