Branching Out / Vol. 6

What to listen to next, based on our recent experiences with the music of Debussy and Puccini.

Welcome to the sixth edition of Branching Out — where works recently featured in Shades of Blue become your launching point for discovering more melancholy music that cultivates calm, connection, and healing. (Head over here to explore previous installments.)

To grow our tree of classical music knowledge this month, we'll explore music based on our recent experiences listening to the hypnotic dreamscape of Claude Debussy's Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, and Giacomo Puccini's "One Fine Day," with its message of hope and resilience in times of despair.

So let's dig in and branch out …

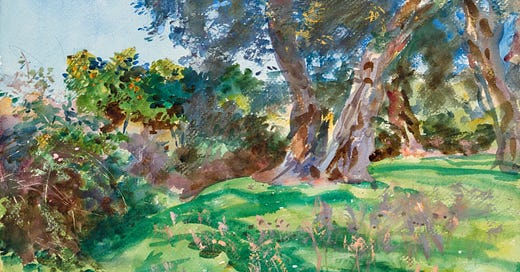

If you loved exploring Debussy's musical portal to a world of Arcadian beauty, where nature is revered for its dazzling divinity, be sure to check out …

Claude Debussy / Pastorale, from Sonata for Flute, Viola, and Harp

In the fall of 1914, Debussy's deep well of inspiration had seemingly run dry. Europe was marching deeper into the fog of World War I, and the colorectal cancer that would kill the composer four years later left him in a state of chronic pain. Unable to put pen to manuscript paper, Debussy wrote to his publisher:

"I won't talk about two months during which I haven't written a note, nor touched a piano: that is of no importance compared to current events. But I can't help thinking about it with sadness . . . at my age, time lost is lost for ever."

By early 1915, however, Debussy was back at it, embarking on an ambitious project to write six sonatas for various instrumental combinations — a musical form he had yet to explore in his wide-ranging career. For the second of these sonatas, Debussy called for three instruments that had never before been assembled as a trio: flute, viola, and harp.

Although the sonata stands as a piece of absolute music — meaning it doesn't convey a specific story or program — the character of Debussy's music takes us back to the mythology and Symbolist poetry that had fascinated him when composing his Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun. The flute, so central to the Prelude, once again evokes the sensual heat of Dionysian pleasure, the harp mirrors the gallant songs of Orpheus and his lyre, while the plaintive, ethereal voice of the viola — capable of singing like the flute and plucking its strings like the harp — serves as a bridge between the two.

Perfumed with poetic nostalgia, especially in the opening Pastorale, the music often feels like it stands outside of time, simultaneously ancient and modern, while its emotional palette moves seamlessly between ecstasy and melancholy. Even Debussy couldn't tell which feelings dominated the new work, explaining in a letter:

"It belongs to that time when I still knew how to write music. It even recalls a Claude Debussy of many years ago. It is frightfully mournful and I don't know whether one should laugh or cry — perhaps both?"

It's little wonder the composer reached across the years to reconnect with the music of his younger days. With Paris under siege and his health deteriorating, perhaps returning to the sound world of his Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun brought Debussy the same sense of reverie and pastoral bliss his music conjures for us today — and the Sonata for Flute, Viola, and Harp was his way of channeling those emotions and memories during a time of monumental loss.

As Germans bombarded the French capital in March 1918, Debussy died quietly at home, having completed only three of his six planned sonatas. Once the war ended, his body was interred in the city's Passy Cemetery, fulfilling his desire to rest for eternity "among the trees and birds" — the kind of sun-drenched landscape he evoked so beautifully in his music.

Magali Mosnier, flute Antoine Tamestit, viola Xavier de Maistre, harp

If you were moved by Puccini's aria from Madama Butterfly, and the ways music and text can unite to manifest light in moments of darkness, then spend some time with …

Igor Stravinsky / "No Word from Tom," from The Rake's Progress

In the 1730s, English artist William Hogarth produced A Rake's Progress — a series of eight paintings that trace the Faustian story of Tom Rakewell, whose life takes a series of tragic turns after receiving an unexpected fortune. Accompanied by the devilish Nick Shadow, Tom heads to London to claim his inheritance, but instead of returning home to his fiancée, Anne Trulove, he descends into a life of sex, booze, and gambling. After losing all of his newfound fortune and marrying another woman (a bearded lady named Baba the Turk), Tom takes his final breath as a patient in London's notorious Bedlam mental asylum.

While Hogarth's paintings focus exclusively on Tom's story, Igor Stravinsky's 1951 opera (featuring a libretto by W. H. Auden and his longtime friend and lover Chester Kallman) fleshes out the character of Anne, whose devotion to Tom — as her surname suggests — knows no boundaries. At the end of the opera's first act, Anne is wracked with nerves as to why Tom has yet to return home. Under the gaze of the full moon, she sings of her worries and doubts:

No word from Tom Has love no voice, can love not keep A Maytime vow in cities? Fades it as the rose Cut for a rich display? Forgot! But no, to weep is not enough He needs my help Love hears, love knows Love answers him across the silent miles, and goes

Her conundrum weighs heavily on Anne's shoulders: Should she head to London in search of Tom? Even if it means leaving her ailing elderly father behind?

Just as Anne's emotions progress from confusion and anxiety to hope and strength, so does Stravinsky's music change character over the course of the aria, growing brighter and more energetic as Anne's bravery blossoms. She ultimately decides that, yes, she will travel to London to rescue her true love. Accompanied by jubilant fanfare in the orchestra, a determined Anne brings her aria to a close by doubling down on the trust she places in love's enduring power:

What he may be I go, I go to him Love cannot falter Cannot desert Time cannot alter A loving heart An ever-loving heart

Dawn Upshaw, soprano Orchestra of St. Luke's David Zinman, conductor (Follow along with Auden and Kallman's text.)

I'd love to hear about your experiences listening to this music. Let me know either by replying to this email or leaving a comment. (And if you enjoyed your time here today, would you ever so kindly tap that little heart below? 👇🏼)

Thank you for reading Shades of Blue! This newsletter is free, but paid subscribers help support the 20+ hours of research, writing, editing, and production that goes into every essay. If you look forward to reading Shades of Blue, please consider becoming a paid subscriber …

… or make a one-time donation through Buy Me a Coffee:

Obsessed with the Debussy sonata... the harp flute and viola trio is so pretty... I love the amount of negative space and how each instrument has such a clear voice. It's also inspiring to read how these composers are so affected by literature and create their own spinoffs of it. Very beautiful to see art conversing across mediums like that. And the singer 😵💫 how?!

I listened to Debussy three times! It’s so complex! You’re right, both ancient and modern. The intro feels like the harp and flute invite the viola in, though the viola is unsure she belongs on this journey. But they all eventually go on their merry way to explore. There’s a wide open field, a small gnarly forest of trees, a babbling brook that builds into a stream, sun that sparkles on the water and surrounds the ground in dappled light, a bit of a tumble down a hill, but no one is worse for wear, night falls and there’s stargazing as points of light begin to appear one by one up above, the fire crackles, and sleep comes softly and swiftly after such an adventure. Magnificent!

And Dawn Upshaw, what a voice!! Such range and emotion, especially in her lower register. This one just feels like it would be such a thrill, albeit incredibly challenging, to perform!