Henryk Górecki / Symphony of Sorrowful Songs

Celebrating Shades of Blue's first birthday with the work that inspired my exploration of melancholy classical music.

Hi, friends,

Shades of Blue turns one year old tomorrow!

It's hard to believe I've been working on this newsletter for 12 months already, inviting readers to slow down and reflect on the calm, connection, and healing made possible by melancholy moments of classical music. Thanks to everyone who's shared my work here with friends, family, and colleagues, Shades of Blue is now read by 984 people in 68 countries around the world.

Mind. Officially. Blown. I am so grateful for each and every one of you.

Marcus Aurelius reminds me every day that "the soul becomes dyed with the color of the mind's thoughts," and I'm grateful for the ways my soul has been enriched by deep reflection on the music we've shared and the thoughtful community that's grown around this newsletter. No matter how challenging life has been over the past year, it's been such a comfort and joy to sit with this music and find the words to express the ways it transports us to a beautiful, more perfect world.

In honor of the milestone, I'm revisiting the work that inspired me to start Shades of Blue — Henryk Górecki's Third Symphony, better known as the Symphony of Sorrowful Songs. Here you'll find a revised version of the essay that launched this newsletter, as well as a new postscript highlighting two connections between Górecki's symphony and another of my favorite music genres: trip-hop.

I hope you enjoy. And thank you, always, for being here.

— Michael

The way classical music is marketed often leaves me furrowing my brow. Especially when I hear the words classical crossover, a term record label executives apply to classical music albums purposefully packaged and positioned to find success with "mainstream" audiences.

Neither the marketer nor the musician in me sees how this approach does anything but alienate the product. It presents classical music as such a fringe element of our culture that a successful recording must include a superstar name, a glossy cover image of said superstar keeping it "cool" or "sexy," and mediocre orchestral arrangements of pop hits to convince music lovers at large to take a chance on a classical artist. (Case in point: Soprano Renée Fleming's cringy deep-dive into Arcade Fire, Death Cab, and Tears for Fears.)

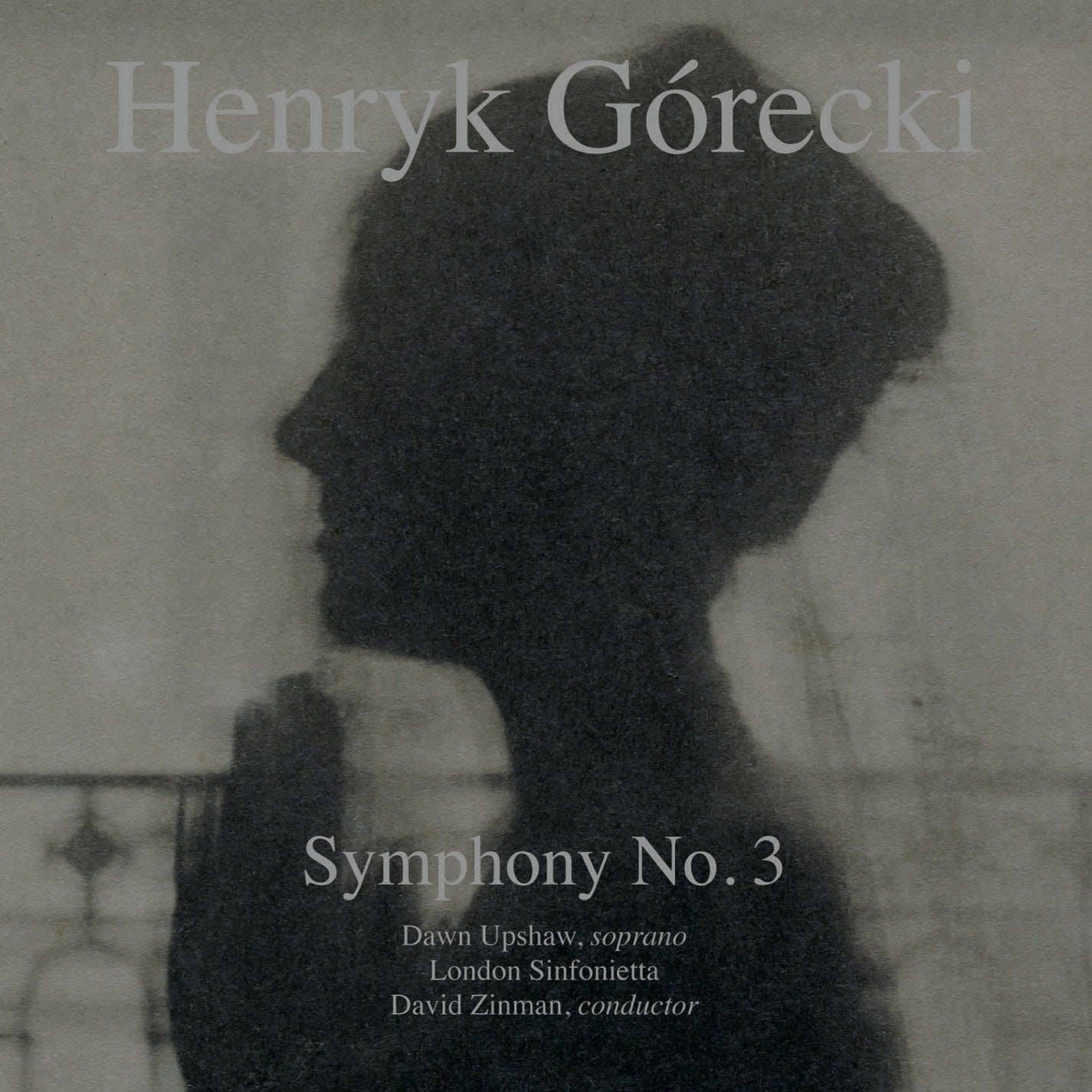

In 1992, Nonesuch Records shot a hole through every one of those assumptions about classical music marketing, when it released an album that took the world by storm — without following the classical crossover playbook. The music was largely unknown, the composer an obscure figure to anyone who wasn't already a die-hard fan of contemporary classical music, and the cover art was simply a fuzzy, gray-scale image of a shadowy figure in profile, hands pressed together in peaceful reverence.

The album featured just one composition: Symphony No. 3, the Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, from Polish composer Henryk Górecki (pronounced Hen-rick Gore-et-skee). Written in 1976, Górecki's symphony is a vast, hour-long work for orchestra and solo soprano in three movements, each one setting a Polish text that explores motherhood and grief, war and loss: a 15th-century lament of the Virgin Mary, a prayer etched onto the wall of a Gestapo prison cell, and the song of a mother searching for her son killed in battle.

The record executives at Nonesuch thought the symphony, performed by the London Sinfonietta and featuring a young singer named Dawn Upshaw, would resonate with listeners. They hoped to sell 25,000 to 30,000 copies.

A year after its release, the album had sold more than 600,000 copies.

It sat at the top of the U.S. Billboard classical chart for a staggering 38 weeks and remained in the top 40 for nearly three years. And in the U.K., the album made its way to the pop charts — read that again, the British pop charts — where it peaked at number six, sandwiched between En Vogue's Funky Divas and R.E.M.'s Automatic for the People.

To date, it's sold more than a million copies, making it the best-selling album of a piece of contemporary classical music.

Why was a largely unknown work, saturated in sorrow with texts written in Polish, such a runaway hit in the English-speaking West?

The album's success was partly due to the extensive air time the symphony's central movement received during the launch of a new British radio station for classical music, Classic FM. At 10 minutes long, it was the only movement that could be easily slotted into a disc jockey's queue (the first and third movements clock in at 25 minutes and 17 minutes, respectively). Interest in the work increased as listeners discovered the emotional impact of the music's profound simplicity — its entrancing, meditative mood, anchored by a modest, unadorned melody in the soprano that rises and falls with effortless, slow-moving grace.

Then, of course, there's that mysterious subtitle: Symphony of Sorrowful Songs. Four words so seemingly abstract, yet specific enough so as to leave no doubt this work was a portal to a very particular emotional world. (The Nonesuch execs couldn't have asked for a better headline for their marketing.) Between the evocative title and the shadowy cover art, it was clear this wasn't an album to fire up for a morning jog or Sunday brunch.

And people bought it anyway — in droves.

No one was more surprised at the success of the Nonesuch album than Górecki himself. None of his works had ever captured — and none would again capture — the public's interest like his Symphony of Sorrowful Songs. When asked about the piece's unexpected popularity, the composer said:

"Perhaps people find something they need in this piece of music. ... Somehow I hit the right note, something they were missing. Something, somewhere had been lost to them. I feel that I instinctively knew what they needed."

If there was ever a composer equipped to write a symphony that speaks to heartbreaking loss and sorrow, it was Górecki. He was born in Poland in 1933, the same year Hitler and his party came to power. His mother died when little Henryk was just two years old. His hometown of Czernica — in the Silesia region of Poland, just 20 minutes away from the concentration camps at Auschwitz — was so polluted that falling snow turned an ashen black in its journey from sky to ground.

But you wouldn't necessarily guess any of that as you begin listening to the symphony's second movement. The motive repeated throughout its opening bars blossoms, radiating a warmth and gentle glow that comforts as much as it transfixes. But as the mood shifts and a dark hush takes over the orchestra, we realize the light we perceive is not that of a clear blue sky, but a singular sunbeam penetrating a deep darkness.

Górecki has set the scene for the song's text, a prayer written by Helena Wanda Błażusiakówna, an 18-year-old prisoner who etched the text on the wall of a Gestapo cell in Zakopane, Poland, with a fragment of her own broken tooth:

Mama, do not cry, no Most pure Queen of Heaven Support me always Hail Mary

The soprano imparts the first line — three quiet, quivering calls of Mama — in her huskiest low register, whispers of consolation as time stands still in the orchestra's static bed of string sound. But as Helena transfers the subject of her prayer from her biological mother to the Holy Mother of God, the music moves slowly upward, each phrase of the text infused with new layers of luster. After her appeal to the Virgin Mary, the soprano returns to repeated calls of Mama, this time singing the blossoming, comforting melody the violins presented at the start of the movement.

Helena's words don't convey messages of fiery anger or frustration — instead, they speak of love and consolation. And that's exactly why Górecki chose to set her prayer in his symphony. In an interview, he shared that:

"I have always been irritated by grand words, by calls for revenge. ... In [the Gestapo] prison, the whole wall was covered with inscriptions screaming out loud: 'I'm innocent,' 'Murderers,' 'Executioners,' 'You have to save me.' Adults were writing this, while here is an 18-year-old girl, almost a child.

"And she is so different. She does not despair, does not cry, does not scream for revenge. She does not think about herself, whether she deserves her fate or not. Instead, she only thinks about her mother, because it is her mother who will experience true despair. This inscription was something extraordinary."

Through Helena's words, Górecki saw an opportunity to express how love could eclipse grief, how much our lives are driven by forces outside of our control, how we can heal ourselves by attempting to alleviate the pain of others.

Love, release, healing — and one final element added by the composer. After the first words of the Hail Mary, which the soprano sings perched aloft one note, floating far from the gravelly depths from which the movement began, Górecki ends his song by adding the remainder of the Catholic prayer's opening line: Full of grace.

Take a listen …

Dawn Upshaw, soprano London Sinfonietta David Zinman, conductor

I'd love to hear about your experience with Górecki's sorrowful song. Are you overcome by an overwhelming sadness, or does the movement's meditative quality take hold of you, as slices of divine shimmer cut through the dark atmosphere surrounding them?

Perhaps you feel all those things — perhaps you feel a whole lot more. Be sure to let me know by replying to this email or leaving a comment below.

Postscript: Górecki's symphony meets trip-hop

In the early 1990s, as Seattle grunge was taking over radio waves in America, a new style of electronic music was emerging in the port city of Bristol, England: trip-hop. Crafting an intoxicating fusion of hip-hop, acid jazz, blues, turntable scratches, and icy orchestral strings, trip-hop artists like Portishead, Tricky, and Massive Attack crafted brooding, melodramatic worlds of sound that would have been right at home in a film noir.

Gen Xers found trip-hop an ideal soundtrack for reflecting on the ennui and alienation of the time, while clad in our oversized flannel shirts and submerged in a sea of cigarette smoke. It also helped Górecki's Symphony of Sorrowful Songs reach new audiences, thanks to the band Lamb and Beth Gibbons, Portishead's chanteuse of sorrow.

Five years after Nonesuch released its blockbuster recording of Górecki's symphony, the British duo known as Lamb — singer Lou Rhodes and drummer-producer Andy Barlow — sampled music from the symphony in "Górecki," the lead single from their 1997 self-titled debut album.

Two alternating chords from the symphony's second movement — one in a consoling major key, the second in shadowy minor — serve as the backdrop for Lou's tender, raspy vocals, her words evoking the feelings of serenity love brings us:

If I should die this very moment I wouldn't fear For I've never known completeness Like being here Wrapped in the warmth of you Loving every breath of you Still my heart this moment Oh it might burst

Layers of drums, electronic beats, and thick bass drones from Andy add urgency and energy, amplifying the song's emotional intensity as we arrive at its chorus of ecstasy:

Wanna stay right here 'til the end of time 'Til the earth stops turning Gonna love you 'til the seas run dry I've found the one I've waited for

"Górecki" peaked at #30 on the UK singles chart and was featured in movies like I Still Know What You Did Last Summer and Moulin Rouge, where Nicole Kidman, as the showgirl Satine, sings the song's opening lines before succumbing to consumption.

Twenty years after the release of Dummy, the 1994 debut album from Portishead, the band's lead singer, Beth Gibbons, sang the soprano solo for a performance of Górecki's symphony with the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra and conductor-composer Krzysztof Penderecki (who had been a close colleague of Górecki's). Not knowing a word of Polish, Gibbons studied the language and Górecki's score for years before taking the stage.

While a soprano like Dawn Upshaw brings grandeur and breadth of sound to the piece, Gibbons's hushed, dulcet alto proves an equally ideal messenger of the poetry's hope and pain. The performance was released in 2019 as a live album, receiving critical acclaim in the alternative press, with the British magazine Q calling the performance:

"a thing of grief-blasted beauty, with Gibbons bringing tender pain to these words of lost children and mothers, her voice rising and falling impressively to the occasion."

Take a listen and let me know what you think of Beth's singular take on this music. (And if you're unfamiliar with Portishead, treat yourself to my favorite of the band's torch songs, "Roads.")

Thank you for reading Shades of Blue! This newsletter is free, but paid subscribers help support the 20+ hours of research, writing, editing, and production that goes into every essay. If you look forward to reading Shades of Blue when it arrives in your inbox, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

In honor of the newsletter's first birthday, you can currently save 20% on a monthly or annual subscription:

Or you can make a donation to support this newsletter through Buy Me a Coffee:

Happy Blueversary, Michael!!! 🎉✨💙✨🎉 I still remember listening to this as I was lying in my Airbnb bed in Des Moines! I remember thinking how the song sounded hopeful, how it shimmered! But now I get the Beth Gibbons version too?! Oh how I LOVE this rendition, thank you for adding it! I had no idea (nor had I ever made the Lamb/Moulin Rouge connection). I honestly feel like Beth poured her whole being into this. So haunting, but again: hopeful, determined. Needless to say, you’ve introduced me to SO MUCH in this past year. I know how much of yourself you pour into this project (I wouldn’t even be surprised if you dream in Blue!) I’m just so grateful for that work and that we crossed paths 💙 Congratulations and Cheers to another year!🥂

Happy first birthday. I so much enjoyed listening. such beautiful music. It really brought out so much emotion in me and some tears