Revisiting an intimate serenade written in the language of friendship

Franz Schubert / Piano Trio No. 1

Hi, everyone,

It's often said the most stressful experiences in life are death, divorce, and moving — and I'm currently enduring all the anxiety and fatigue that comes with the third entry on that list.

So since my days currently involve chanting "SERENITY NOW!" while packing boxes and planning logistics for transporting 81 potted plants, I've decided to dig into the archives for today's edition of Shades of Blue.

What do David Bowie, pansexual vampires, and the music of Franz Schubert have in common? Read on to find out!

— Michael

This time of year, as Halloween creeps ever closer on the calendar, a craving for gothic vampire films consumes me. If I'm in the mood for opulent sets and costumes, I'll turn to Bram Stoker's Dracula and Gary Oldman's tour de force performance. If I want a heavy dose of homoeroticism, I'll revisit Neil Jordan's campy, blood-soaked adaptation of Anne Rice's Interview with the Vampire. And for a gritty, modern take on the vamp genre, I have to go with The Hunger.

Starring Catherine Deneuve, David Bowie, and Susan Sarandon, the 1983 cult classic ticks a lot of aesthetic boxes for me — including the heavenly vision that is Deneuve in Dynasty-style power suits, shadowy cinematography that evokes the Italian Baroque, and a sweaty opening sequence that pulsates with Bauhaus's goth anthem "Bela Lugosi's Dead." But the aspect of The Hunger I love most: Miriam and John, the centuries-old vampire lovers played by Deneuve and Bowie, spend their days posing as an elegant Manhattan couple who teach — what else? — classical music.

Early in the film, it's time for a lesson with one of their pupils, a teenage violinist named Alice. The three assemble in Miriam and John's spacious townhouse parlor to rehearse the slow movement of Franz Schubert's Piano Trio No. 1. Miriam sits poised at the piano as she introduces the gently rocking accompaniment that sets this bucolic music in motion, over which John's cello sings a melody suffused with longing and melancholy. Alice exchanges a faint smile with Miriam as she waits for John to pass her the melodic baton.

This scene always tickles me. Not only because we get to see A-list Hollywood actors engaging with classical music on screen, but also because the film takes Schubert's trio and returns the work to the environment for which he wrote it — the home. Although performances of the trio nowadays take place on large stages in acoustically engineered concert halls, Schubert composed this genre of music — aptly called chamber music — to be played at home, near a crackling fire, by friends who sway to and fro as they explore every contour of the music together.

At the dawn of the 19th century, domestic music-making in Europe had achieved new levels of accessibility and popularity. No longer confined to the monarchy's grand palaces or the stately homes of the aristocracy, music became a fixture of daily life in many middle-class households like that of the Schuberts. The son of a schoolteacher, little Franz was surrounded by music from an early age. A gifted singer and pianist, he also learned the viola so he could play in a string quartet with his father and brothers. And by his late teens, when Franz began composing full-time, private salons had become the hottest spots in Vienna for enjoying intimate evenings of music.

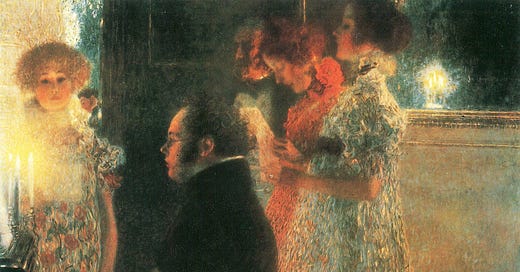

Franz was part of a tight-knit band of bohemians who collectively explored liberal ideals, flouted the tenets of Vienna's ultra-conservative society, and embraced their passion for art, music, and literature. His friends revered Franz and his music, and even regularly produced concerts, known as Schubertiades, in the homes of wealthy patrons. The focus of these evenings — aside from good food, flowing wine, and riotous laughter — was always a performance of the latest music to flow from Franz's pen.

Many of Franz's compositions — including more than 600 songs, nine symphonies, chamber works, sacred masses, and a wealth of music for solo piano — are laced with a sweet sadness that mirrored the composer's complex emotional palette, which a close friend described as a "mixture of tenderness and coarseness, sensuality and candor, sociability and melancholy."

No one recognized Franz's heart-on-sleeve spirit more than Franz himself. In a short story he wrote in 1822, the central character, who clearly serves as a stand-in for the composer, says:

"Through long, long years I sang my songs. But when I wished to sing of love it turned to heartache, and when I wanted to sing of heartache it was transformed for me into love."

These are moving words from an artist regarded as one of the finest observers of the human condition, who could express a profound understanding of seemingly every emotion swirling about the deepest chambers of the heart. Especially in his extensive song catalogue, we hear how Franz recognized the yin and yang of life, the ways love and happiness are inextricably laced with isolation and sadness.

It's often said that when Schubert writes in a major key, the music sounds even sadder than when he writes in a minor key — as if he's showing us that any sense of relief, joy, or calm is fleeting in a world filled with so much grief and despair. And as we hear in the slow movement of the First Piano Trio, with its achingly tender conversation among violin, cello, and piano, just because those feelings are fleeting doesn't mean we can't savor every moment of their fragile beauty.

Written in a state of deepening depression during the final year of Franz's life — a period of rapidly declining health that stemmed from his contracting syphilis five years earlier — the First Piano Trio speaks to the pleasure and fulfillment he received from his close musical collaborations. Clocking in at 45 minutes and following the four-movement structure typical of 19th-century symphonies, Franz's trio could have easily been written for a grand orchestra. But instead, he composed a symphony in miniature — one he could perform with friends at their frequent get-togethers.

Creating that level of intimacy was a natural fit for a composer of songs. In fact, the trio's slow movement is in many ways a sublime song without words — one that immediately evokes feelings of Gemütlichkeit, the German term for feelings of profound warmth and comfort.

The cello sets the scene with an expansive serenade. Seemingly tentative at first, the line builds upon a series of sighs that soar higher in the instrument's resplendent tenor until it's handed over to the violin, whose silvery soprano amplifies the melody's sweetness. Even in the movement's central section — where the piano takes a suspenseful turn and introduces a new minor-key tune driven by riveting off-beat rhythms in the strings — we can't help but be moved by the delicate interlacing of voices, which playfully mimic each other without ever mocking. Together the trio embarks on a voyage through distant harmonies, the music's playful twists and turns mirroring the many circuitous routes a late-night conversation among friends can take.

Then, following a moment of supremely satisfying suspension and resolution, the opening material returns, seemingly with more longing than before, as violin and cello take turns singing the serenade theme above broken chords in the piano that resemble the plucking of a celestial harp. Our journey here ends in a state of hushed reverie — the earthbound cello settling into its deepest register, the violin reaching for the stars, as their lyrical dialogue evaporates into breathtaking silence.

That gentle weaving together of voices, the way each instrument supports its companions with such care and compassion — this is music of deep human connection, composed using a language of friendship Franz lovingly etched into every measure of his manuscript. It's a balm that has comforted and consoled listeners for nearly 200 years. The composer Robert Schumann, one of Schubert's greatest advocates in the decades following his death in 1828, remarked:

"One glance at Schubert's trio and the troubles of our human existence disappear and all the world is fresh and bright again."

I get misty-eyed every time I read that quote — a powerful reminder that art always offers opportunities to reframe the world around us, even if just for the nine minutes it takes to experience this lullaby of longing. It's an idea I've needed to hold close even more these days, as we're forced to confront unceasing waves of division, hatred, and brutality across the globe.

In those moments when my heart feels its heaviest, I sit with this music and dream of living in a world where humans communicate using Franz's language of friendship. Wouldn't that be lovely — to speak to one another in phrases offered with nothing but love and respect, kindness and affection?

Take a listen …

Christian Tetzlaff, violin Tanja Tetzlaff, cello Lars Vogt, piano

Among the many recordings of Schubert's First Piano Trio, my favorite is one released in early 2023 by pianist Lars Vogt, cellist Tanja Tetzlaff, and violinist Christian Tetzlaff (Tanja's brother). Close friends and musical partners for more than two decades, they had previously recorded Schubert's pair of piano trios almost two decades ago before preparing a new recording in 2021.

But this would prove no ordinary recording process. Shortly after completing the album's first studio session in February, Lars was diagnosed with an aggressive case of throat and liver cancer. Committed to completing the project despite the chronic pain and fatigue he experienced, Lars scheduled his ongoing chemotherapy appointments to accommodate a second recording session in June.

Although he had been a prolific performer of Schubert's music throughout his career, Lars's diagnosis must have added new layers of resonance to the melancholy music written by a composer who had died from a devastating disease at 31. After listening to the edited album for the first time, he texted Tanja and Christian to express his enduring gratitude for their love and friendship, and the music they shared:

"Now we've done it, recorded these trios — now I could go too. ... If not much time remains, then it's a worthy farewell. You two are absolutely fantastic. And Franz. Incomprehensible. Such expression. Such fragility, such love."

A worthy farewell, indeed, for a musician of incomparable kindness and artistry. Lars Vogt passed away on September 5, 2022, at the age of 51.

I'd love to hear about your experience listening to Franz's melancholy ode to music and friendship. Does it conjure in you the same daydreams of peace and human connection I feel? Let me know by replying to this email or leaving me a note in the comments.

(And if you enjoyed your time here at Shades of Blue, how about tapping that little heart below? 👇🏼)

Thank you for reading Shades of Blue!

This newsletter is free, but paid subscribers help support the 20+ hours of research, writing, editing, and production that goes into every essay. If you look forward to reading Shades of Blue when it arrives in your inbox, please consider becoming a paid subscriber …

Or if you'd prefer to buy me a coffee as a token of thanks for this article, you can make a one-time donation to support this newsletter:

Lovely article Michael, and you have my full sympathy going through a move. 😱 81 potted plants and I'm just contemplating buying one, after reading another excellent Substack article this week which relayed all the benefits of house plants. Coincidence.

It's years since I saw "The Hunger", and lovely to see that clip of DB and Deneuve 💛

Really enjoyed it as usual. So sad about Lars Vogt. A beautiful recording to leave the world.

Good luck with the move. Hope you are soon in your new nest and all the chaos behind you x

A Seinfeld fan, on top of being such a remarkable music connoisseur. It's almost a Festivus miracle. Thank you for every recommendation.