W. A. Mozart / Fantasy in D Minor

What can a pair of "unfinished" works by Mozart and Alice Neel teach us about how we communicate with art?

One of my prized possessions as a teenager was a boxed set of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's complete works for solo piano. I discovered this treasure in the summer of 1995 at a Borders Books & Music in suburban Connecticut, where it sat shrink-wrapped and dusty on the bottom shelf of a display of discounted books.

I didn't hold the box set in high regard because I could play much of the music inside. Although I had taught myself some beginner piano technique and was competent enough to accompany friends singing Broadway and pop tunes, Mozart's music demanded skills that were beyond me. Instead, I loved feeling the silken, cream-colored paper against my fingertips, watching the notes playfully dance across the music staffs, and absorbing with total awe the vast amount of creative joy — representing more than 30 years of composing — embedded in those beautifully bound books.

There were a few pieces I could play well enough, little jewels I cozied up to throughout the years. But one became a complete obsession: the Fantasy in D Minor — a short free-form work, just 107 measures, that Mozart wrote in 1782, one year after leaving his Austrian hometown to make it as a freelance musician in Vienna.

In contrast to the buoyant, energetic side of Mozart I knew — the perennially popular Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, the magisterial power of the "Jupiter" Symphony, the music-box precision of his Clarinet Concerto — the Fantasy in D Minor beckoned me into a world of shadows and twilight. It's a work one imagines performing as a midnight missive, the score illuminated only by the flicker of a lone candle.

From the opening bar, we're met with the quiet, hypnotic rise and fall of broken chords — like the sound of Orpheus's lyre echoing from the depths of the underworld. But almost as quickly as this passage begins to cast its spell, Mozart calls for silence before introducing the piece's main material. Above a simple accompaniment in the left hand, a melody of mystery and operatic grace spins in the right hand — moving step by step, ornamented by gentle turns of phrase and entrancing alternations between long and short notes.

Then, again, silence.

(As we heard last month in Debussy's Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, the silences in music can be just as gripping as the music itself.)

Now a tolling of bells takes over in the right hand as a trio of lower voices descends, increasing the intensity of the moment, until melody and accompaniment come to a fleeting détente. An anxious back-and-forth ensues, the music suddenly breathless, agile, climbing higher and higher until reaching its breaking point — followed by a furious cascade of notes that plunges into the depths of the piano's keyboard before evaporating into thin air.

Mozart bases much of the Fantasy on these four motives: the achingly beautiful melody, the lamenting bells, the anxious chase scene between hands, and the rapid ripples of notes. Finally, a new theme emerges in a brighter, happier key of D Major — a simple little tune that gradually gains energy and brings the Fantasy to a jovial conclusion.

That enthusiastic ending never satisfied me. After journeying through the dark night of the soul in the D Minor passages, it seemed too hasty to think a minute of music abruptly presented in a sunny major key could wrap things up so succinctly and send me on my way. No one can shed such a deep melancholy so quickly.

As I later learned, Mozart didn't write that ending.

The Fantasy in D Minor is a fragment, a work left incomplete for no reason we can ascertain today. Perhaps he intended to pair it with a fugue in the style of Johann Sebastian Bach. Or perhaps it would become the introduction to a larger sonata for solo piano. We'll never know — but discovering Mozart left the work incomplete has only added to my fascination for it.

Mozart wrote 97 of the 107 measures included in the Fantasy's published scores — ending the work on an unstable chord shortly after beginning the D Major section. The 10 bars that comprise the traditional ending were added by the Leipzig-based music publisher Breitkopf & Härtel in 1806 so the firm could add the work to its sales catalog.

Maybe I'm in the minority thinking the ending is unfulfilling. Most pianists perform this traditional ending, and no one even questioned the authorship of those final bars until 1944. But I've always preferred to stay in the melancholy world of D Minor, and will often stop a recording before the first notes of the D Major ending begin.

Mozart's Fantasy raises questions about what makes a work of art "complete" or "incomplete," "finished" or "unfinished" — and how the fine line between these terms depends on our personal definitions of what art needs to achieve, how much we're able to learn from it, and whether every question we ask of a work requires an answer.

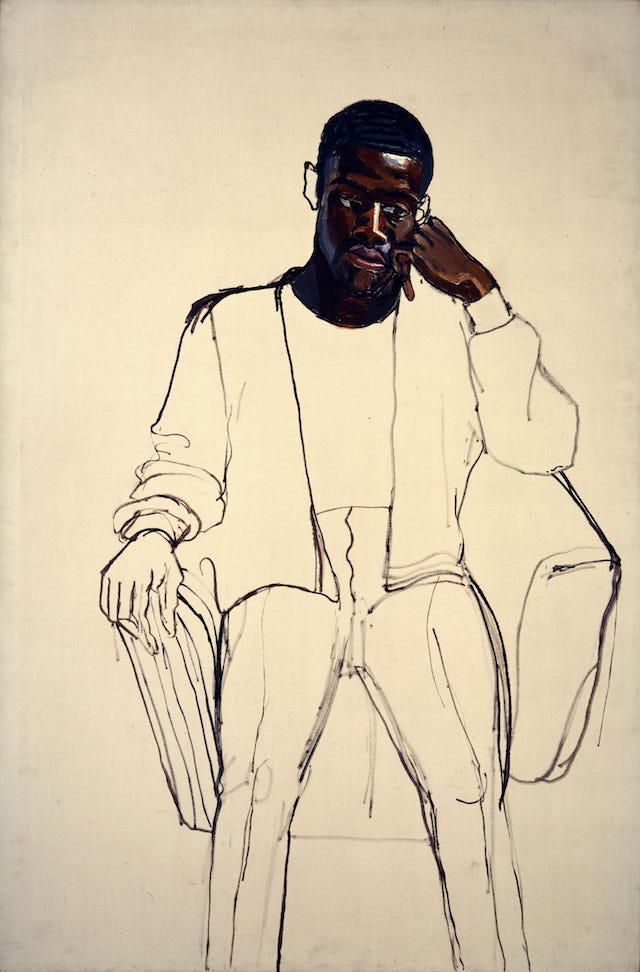

The visual arts frequently contend with such discussions. Take Alice Neel's James Hunter Black Draftee, a portrait the artist painted in 1965 of a young man she met one day in her neighborhood. Hunter had been drafted for service in the Vietnam War and was scheduled to leave New York City for basic training in a week, so they agreed to fit in two sittings before his departure.

In the first session, Neel outlined Hunter's body on the canvas before diving in with oil paints to vividly detail his head and left hand. Unfortunately, Hunter never returned for his scheduled second sitting. Unable to track down any contact information for him, Neel signed the back of the canvas and declared the work complete as is.

One could look at Neel's portrait and call it unfinished. After all, doesn't art history teach us that every inch of a canvas should be covered in paint? That a portrait should evoke every reflection of light on the sitter's skin, every fabric of the clothing they've chosen to be immortalized wearing? Can we really consider a painting complete when the artist leaves more than 90 percent of the surface area bare?

Or is Neel's portrait a complete work of art, in that it speaks to the fragility of life, the countless unknowns that shape the human experience? With that perspective, we can view the portrait as a story punctuated with question marks, a life possibly torn down in the early stages of adulthood fighting in an unjust war thousands of miles from home. Each fine bristled hair of exposed canvas stands in contrast to all the colorful sunsets and flowers left unseen, the many textures — plush blankets, orange peels, the warm skin of a lover's back — left untouched.1

Art isn't a divine oracle, after all. Its inability to answer our questions, to fill in every detail of a story we so eagerly want to hear, is exactly what makes it the work of human creativity.

And as we can hear in Mozart's Fantasy, there's a profound power embedded in each question a work of art leaves unanswered, and the many questions it forces us to ask of ourselves. Even in this raw form, the Fantasy is fragmented yet still complete, in that we're still able to learn so much about life within its notes, the joys and sorrows, the frustrations and miracles laid bare in the process of moving through our everyday lives.

For Mozart, music was simply a way to directly connect with the people around him — his friends, loved ones, and those interested in hearing his art. As Jan Swafford so movingly states in his biography of the composer:

"Much of what sets Mozart apart … was the amity of his music, the art of a sociable man intended for a circle of friends and for small groups of listeners. … Mozart [wrote] for people. What we hear is a gift given to us intimately as friend to friend, lover to lover."

His gift of the Fantasy in D Minor is one I've treasured for three decades and counting. Not because it presents a polished, complete musical idea that overcomes darkness to bask in the shimmering light of day. But because it moves me, draws me into its singular world, allows me to peer behind the curtain and experience Mozart in the thrust of creative heat — a mystical space where I can see his thoughts at work and hear his fantasies take flight.

Take a listen …

As I mentioned earlier, not every pianist performs the Fantasy in D Minor with the traditional ending penned decades after Mozart's death. So instead of sharing one favorite recording of this work, I'm sharing three — each presenting the pianist's vision for how the work should end.

First we have Fazil Say, who performs the Fantasy in its traditional 107-bar form, ending in bright D Major.

Then there's Mitsuko Uchida, one of the most celebrated interpreters of Mozart's music. Instead of performing the traditional ending, she stops at measure 97 — the last chord Mozart wrote — and then takes us back to the shadowy world of the D Minor introduction, following the serpentine curves of the music until we rest on the final bell tone sounded in the cavernous depths of the piano.

Finally there's my favorite recording, by the Icelandic pianist Víkingur Ólafsson, who really leans into the nocturnal nature of the piece. So much so that he eliminates the D Major section altogether, choosing instead to end the work on the mysterious chord that comes before the key change. He invites us to feel the tension of that unanswered question, left to echo, unresolved, in our ears for eternity.

I'd love to hear about your experience listening to Mozart's mysterious Fantasy. And which of the endings resonates with you the most? Let me know in the comments.

If you enjoyed your time here at Shades of Blue, how about tapping that little heart below? 👇🏼

Nothing is known of Hunter's life after his sitting with Neel. It's unlikely he died in battle, however, as his name isn't included on the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, DC.

Michael- Perhaps it’s very apt then that it was called Fantasy in D Minor for reasons you’ve described here: “allows me to peer behind the curtain and experience Mozart in the thrust of creative heat.” Thanks for sharing.

This is a delightful introduction to a wonderful piece by Mozart. And it's also a reflection on art in general and the notion of artistic completion. I really liked the way you connected your discussion of the Fantasy in D Minor and the Alice Neel painting. I had to share a quote from this passage.

Thanks for sharing the links to the three performances of the piece. Great for an evening's listening!